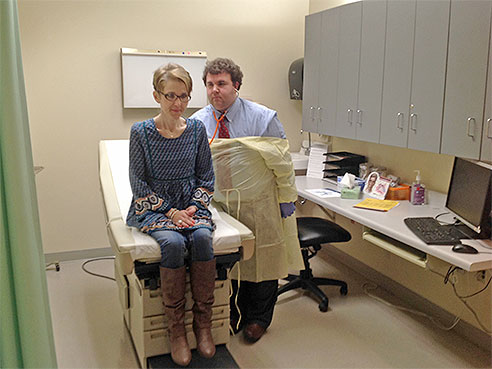

Kathy McRight in clinic with George Solomon, M.D. McRight has PCD, primary ciliary dyskinesia

Kathy McRight in clinic with George Solomon, M.D. McRight has PCD, primary ciliary dyskinesia

Kathy McRight has dealt with respiratory issues since the day she was born. The Florence, Ala., native fought through bouts of double pneumonia, ear infections, sinus headaches, bronchitis and more. She got hearing aids at age 11 and underwent numerous sinus surgeries. For 37 years, she dealt with an illness that no one ever put a name to. It took a brush with death in 2007 for McRight to finally find out what was wrong with her.

The disease is called primary ciliary dyskinesia, or PCD. It was also referred to as Kartagener’s syndrome or immotile cilia syndrome in the past. It’s an inherited disorder that disrupts the tiny cilia in the airways. Cilia are hair-like structures in the lungs, trachea and nose that move in wave-like motions, carrying mucus to the nose and mouth to be coughed or sneezed out of the body.

McRight is now a patient at the new University of Alabama at Birmingham PCD clinic and eager to boost awareness of this rare disease, in hopes of helping others avoid the long, terrifying journey on which she traveled.

In 2007, while in the midst of some major cold symptoms, McRight developed severe respiratory distress. She couldn’t breathe. Her blood pressure dropped to alarming levels and physicians at the small Mississippi hospital near her home at the time bundled her into an ambulance to a larger hospital across the state. Her husband was told she was near death.

Stabilized at that hospital, she saw a pulmonologist — the first respiratory specialist she’d ever seen. He was the first physician to suggest PCD as a possible diagnosis, but it is rare enough and hard enough to diagnose, that he sent her on to a hospital in Colorado. From there she went to specialists at the University of North Carolina, where a firm diagnosis of PCD was finally made.

“They told me I had the lungs of someone who was 70 years old, after all the lung damage that had accumulated over the years,” said McRight. “I was in total shock.”

In patients with PCD, the cilia either don’t work properly, or are not even present in the airway. Mucus, which carries bacteria and foreign matter such as dust, is not moved out of the body, causing infection. About a quarter of those with PCD develop respiratory failure. Some need a lung transplant.

“Staying one step ahead of this disease requires constant therapy and interventions,” McRight said. “Daily life is far from normal.”

The PCD Foundation created a network of clinical centers to focus attention on the disease and provide diagnosis and treatment. UAB joined the PCD Clinical and Research Centers Network in late 2015.

“The first step is to build awareness of this relatively unappreciated and underappreciated disease,” said George M. Solomon, M.D., in the UAB Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, part of the Department of Medicine. “Our goal is to reach the many affected people in our region and help provide an early diagnosis and begin therapy for this disease as soon as possible.”

“The first step is to build awareness of this relatively unappreciated and underappreciated disease,” said George M. Solomon, M.D., in the UAB Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, part of the Department of Medicine. “Our goal is to reach the many affected people in our region and help provide an early diagnosis and begin therapy for this disease as soon as possible.”

Solomon, who is medical director of the new clinic, says it’s the only one in the Deep South, and will cover Alabama and parts of neighboring states along with partners at Children’s of Alabama which has established a complimentary clinic for children with the disease. The PCD Foundation estimates that there are 25,000 Americans with PCD, and less than 1,000 of those have been diagnosed.

There are no approved medications for PCD, but Solomon says that experience has shown that many of the therapies developed over the years for cystic fibrosis seem to have some benefit for those with PCD.

“Some of the airway clearance techniques that we use for CF appear to help some PCD patients,” he said. “Our other focus is research, and the clinic hopes to enroll patients as a research site for a new clinical trial for a novel mucolytic medication — one that may help clear mucus — sometime in late 2016.”

McRight uses airway clearing techniques and nebulizing medicines. Since her diagnosis, she’s had 25 surgeries, 50 bronchoscopies and has been hospitalized 27 times for respiratory infections. She says early detection is important, as lifestyle changes and therapy can help manage the disease.

“By the time I was diagnosed, my lungs were eaten up with bronchiectasis,” McRight said. “I do not want anyone to go years without knowing that they have this disease as I did. PCD has forever changed me, but it doesn’t have to change the next person who is diagnosed.”

To make an appointment at the clinic, call UAB Healthfinder at 205-934-9999 or 800-822-8816, or go to www.uabmedicine.org to make an appointment online.