Jill Clements, Ph.D., associate professor of EnglishFrom Home Depot's sold-out 12-foot skeleton to sheet ghosts on social media, reminders of the (un)dead are no less pervasive in popular culture now than in Halloweens past.

Jill Clements, Ph.D., associate professor of EnglishFrom Home Depot's sold-out 12-foot skeleton to sheet ghosts on social media, reminders of the (un)dead are no less pervasive in popular culture now than in Halloweens past.

The reanimated dead is not a new concept, said Jill Clements, Ph.D., associate professor of English. Clements researches Old English language and literature — specifically medieval views of death and dying and practices of commemoration — and Old Norse-Icelandic literature and culture. Her current book project, “Writing the Dead in Early Medieval England,” examines the interplay of dead bodies and texts in early English commemorative genres and in religious and heroic poetry.

During the medieval period, from about the fifth to the 15th centuries, people in Europe interacted physically with the dead in a significantly different way than we do now, Clements said. More people died at home then, meaning that it was usually the family’s responsibility to prepare the body for burial.

“Our contact with the dead is really limited by comparison,” she said. “People don’t always die at home now. It often happens at a hospital, so they go from the hospital morgue to the funeral home, and may never come back home. In the Middle Ages, it was the family who washed the body, wound them in a winding sheet and dug the grave.”

Across medieval Europe, people were personally involved with the burial process, and many of their stories also revolved around the treatment of dead bodies and graves. In England, tales about the dead were associated with their religious practices, and in Iceland, the dead often featured prominently in the stories about their ancestors. The results are stories about headless saints, spirits haunting people’s dreams and dead bodies who come back to life, sometimes for revenge.

Read through a few spooky stories from medieval England, France, and Iceland to see some of their takes on the walking dead.

An illustration of St. Edmund's martyrdom from a medieval manuscriptA decapitated saint and a talking head

An illustration of St. Edmund's martyrdom from a medieval manuscriptA decapitated saint and a talking head

When the Vikings were raiding England in the ninth century, a saint named Edmund turned himself over to the invaders rather than have his people be overrun, according to Ælfric of Eynsham’s “Lives of Saints.” Ælfric was an English abbot who wrote hagiographies, homilies and biblical commentaries in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Edmund tried to convert the Viking invaders, and in response they tortured and beheaded him, throwing his head into the forest. Contemporary Christian burial customs dictated the head must be buried with the body for sake of wholeness, anticipating the resurrection of the dead at the Last Judgment. A witness who had seen the beheading had an idea where to look, so a search party traveled the woods calling out for Edmund, eventually hearing the head itself respond “Here, here, here!” They find Edmund’s head — which was speaking to them — miraculously being guarded by a wolf, which kept the carrion animals at bay. After the head was recovered, Edmund was given a martyr’s burial.

Years later, Edmund’s body is exhumed from the local churchyard to be moved to a nicer location. Ælfric wrote that his body looked almost entirely healed, and that the head had seemingly reattached to the body, with just a thin red line around his neck, to show where he had once been beheaded.

A forgotten saint haunts a blacksmith’s dreams

Ælfric wrote of another saint, Swithun, whose gravesite had been forgotten by his community. To ensure his veneration and remembrance, Swithun first appeared in a vision to a local blacksmith, telling him where to find Swithun’s grave and how to know it’s his: There is an iron ring on the coffin lid, he told him, and if you can pull it open, then all this has been true. The blacksmith was too scared to follow through, however, and an increasingly frustrated Swithun had to visit him three times before the smith finally went to the grave.

Political turmoil in the local church prevented Swithun’s body from being moved inside the church, so his spirit took another approach. He began appearing to others in the community, telling diseased people to visit his tomb to be healed. Eventually, the king notices the healings and tells the bishop to re-inter Swithun’s body within the church.

After Swithun’s body is moved, more and more people come to the tomb for healing, Ælfric wrote — so much so that the walls were lined with the crutches and stools that had belonged to those who had been healed of their physical ailments.

A 16th-century painting by Matthias Stom of Saul's (right) encounter with the spirit of Samuel (center)A biblical king, a witch and a séance

A 16th-century painting by Matthias Stom of Saul's (right) encounter with the spirit of Samuel (center)A biblical king, a witch and a séance

Ælfric also wrote a homily on the problem of consulting auguries, or omens. He includes the biblical Old Testament story of King Saul’s encounter with the Witch of Endor. In the biblical version, the king asks a medium to raise the spirit of the prophet, Samuel, who, upon being disturbed, becomes enraged with Saul and tells him that the following day both Saul and his entire army will die. Both prophecies are true: The army is vanquished in battle, and Saul commits suicide.

Ælfric contends that witches cannot actually raise the dead — they just conjure the devil in the appearance of the dead person — and attempting to commune with the dead leads to certain damnation, Clements said. In medieval England, practicing any kind of magic was expressly forbidden, so Clements said it’s likely Ælfric brought this story up to address the contemporary issue of practicing necromancy among his readers, especially at ominous places like crossroads where heathens and criminals often were buried.

Ælfric closes the homily by noting that, “Witches still to go to the crossroads, and to heathen burials with their illusions, and call to the devil, and he comes to them in the likeness of the man who lies buried there, as if he arises from death; but she cannot do that — raising up the dead through her magic.”

A dead baker who throws rocks at villagers

Near the end of the Middle Ages, in the 15th century, a story circulated about a baker in Brittany who, after his death, continuously came back to life, much to the chagrin of his village. According to “Ghost in the Middle Ages: The Living and Dead in Medieval Society” by Jean-Claude Schmitt, on the baker’s first resurrection, he returns home, where he attempts to help his family knead bread dough but instead scares them away.

After the neighbors chase him away, the baker returns, throwing rocks at villagers and generally wreaking havoc. Some notice his legs appeared to be covered with mud up to his thighs. When a group of locals dig up his body to make sure he was properly buried, they find his corpse is muddied up in the exact same way.

The villagers tried weighing his body down to keep him in the grave, and when that didn’t work, they resorted to breaking the corpse’s legs; after that, the Breton baker did not rise again.

The popularity of "Eyrbyggja saga" endures; it is still in print today, from PenguinThe determined ghost of a vengeful father

The popularity of "Eyrbyggja saga" endures; it is still in print today, from PenguinThe determined ghost of a vengeful father

An Icelandic family saga titled “Eyrbyggja saga,” or “The Saga of the People of Eyri,” also catalogues several hauntings in medieval Iceland where the walking dead, called “draugr” in Old Norse, sometimes return with malicious intent.

One of the tales is about a man named Arnkel and his father, Thorolf Halt-foot, who died sitting up, eyes open, at the family’s dining room table. Arnkel warned his family not to walk in front of the man’s line of sight; he covered up the face and ordered a hole to be cut in the wall through which Thorolf could be carried out — likely to confuse the body in case the undead Thorolf tried to return home.

Both the oxen who carried Thorolf to his grave died, as did many animals who went near his burial site, and soon Thorolf began haunting the valley, causing farming families to flee left and right. Arnkel decided to move the body, which was “all undecayed, and most evil to look on.” After they moved him to a new gravesite, they built a wall around it in an attempt to keep Thorolf contained.

Soon after, Arnkel was killed, and even the wall couldn’t keep Thorolf’s ghost from returning to attempt to avenge his son. Another group of men exhumed Thorolf’s body yet again, and this time they burn it, scattering the ashes in the sea. Some of the ashes, however, were caught in the wind, and a cow who accidentally ingested them; later she gave birth to a bull who killed a man who had been one of Arnkel’s nemeses.

Robert Louis Stevenson's short story, "The Waif Woman," is based on the tale of Thorgunna; N. C. Wyeth composed this illustration, of the men discovering Thorgunna's ghost in the kitchen, for a 1914 Scribner's printing.

Robert Louis Stevenson's short story, "The Waif Woman," is based on the tale of Thorgunna; N. C. Wyeth composed this illustration, of the men discovering Thorgunna's ghost in the kitchen, for a 1914 Scribner's printing.

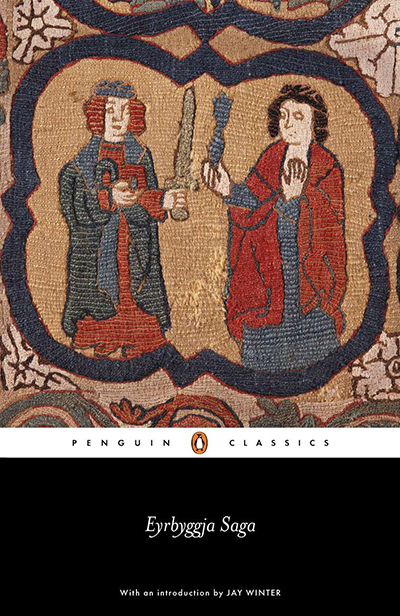

Lessons on hospitality from a Scottish woman’s ghost

In another “Eyrbyggja saga” story,” a Christian woman from the Hebrides named Thorgunna died, leaving a few gifts to the church in exchange for prayers for her soul. As her body was transported for burial, the movers stopped for the night at a farm, where they were refused food, which was against the social customs of the day.

As the movers prepared to go to sleep hungry, they heard a rustling noise in the kitchen — it was the ghost of Thorgunna, completely naked, preparing a meal for the men. The farmers, who had originally refused hospitality to the group, were scared, and subsequently promised them food, dry clothing and whatever else they needed for their journey. Thorgunna was soon buried, and her ghost never bothered anyone after that.

A servant wrestles with an undead farmer

Another Icelandic saga, the “Laxdæla saga,” meaning “The Saga of the People of Laxardal,” was written in the 13th century and tells the story of a violent man named Hrapp, who, on his deathbed, requested to be buried vertically in the doorway of his home so that he could keep an eye on his house and family.

According to the saga, Hrapp became a draugr and “walked again a great deal after he was dead,” killing most of his servants in their encounters. They eventually relocated his body, but it didn’t take and the farm was abandoned. When a man named Olaf later took over the property, one of his servants came to him, terrified, saying that Hrapp wouldn’t leave the threshold of his former home — and that the servant had physically wrestled with him trying to remove it.

When Olaf went to investigate, he struck at Hrapp with his spear, but Hrapp broke the spearhead off and disappeared. When Olaf and a group went to Hrapp’s new gravesite the next day, they found Hrapp entirely undecayed. Olaf’s spearhead was buried with him. They eventually dug Hrapp up, burned his body, and cast his ashes into the sea, and never had trouble after that.

This story was originally published in October 2017 and updated in October 2023.