Click to enlargeSome things don’t hit home until you see them with your own eyes. For Lisa McCormick, it was standing on the banks of the Mississippi River in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, looking up at the levee walls that failed and nearly drowned a city during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Click to enlargeSome things don’t hit home until you see them with your own eyes. For Lisa McCormick, it was standing on the banks of the Mississippi River in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, looking up at the levee walls that failed and nearly drowned a city during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

The neighborhood has long been one of New Orleans’ poorest. When Katrina hit, the average resident survived on $16,000 a year. One out of every three residents lived below the poverty line — $9,570 that year.

Pulling on the thread of poverty in the Lower Ninth dredges up some of the city’s more ignoble past. When the city’s earliest settlers moved to New Orleans, they bought up the high ground, forcing poor residents, many of whom were free people of color, into the low-lying areas, according to a report from the Data Center. Zoning laws in the early 1900s kept black residents from living in white neighborhoods, and by the mid 1930s, federally backed lending maps almost exclusively designated the city’s black neighborhoods as “hazardous,” meaning residents could be refused a loan or other bank service based on their residence there.

The Lower Ninth produced a long record of health disparities within the neighborhood — something that intrigues McCormick, an associate professor in the department of environmental health sciences and the associate dean for public health practice. Laws and ordinances that prevented significant economic growth in majority-black neighborhoods also precluded residents from accumulating generational wealth, which would have enabled them to relocate to a more economically diverse neighborhood and access better health care and education.

Students visited the Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University, where West African smallpox posters were on display.Instead, McCormick said, many found themselves stuck in the Lower Ninth — a fact she’d always known as an academic yet didn’t fully understand until she saw the levee walls for herself.

Students visited the Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University, where West African smallpox posters were on display.Instead, McCormick said, many found themselves stuck in the Lower Ninth — a fact she’d always known as an academic yet didn’t fully understand until she saw the levee walls for herself.

“You really don’t understand it unless you’re standing there along that levee wall with the sea-level Mississippi River on one side and ground about a dozen feet lower on the other side,” she said.

|

“You learn about a lot of things in the classroom, but to see public-health practices in the field and see how we can affect communities in a positive way — that’s important for students.” |

McCormick was in New Orleans during a two-week long trip across the Southeast with Meena Nabavi, program manager for the Office of Public Health Practice, and 15 public health students — six undergraduates, eight graduate students and one doctoral student — visiting health departments and discussing community health and the social determinants that influence it.

“You learn about a lot of things in the classroom, but to see public-health practices in the field and see how we can affect communities in a positive way — that’s important for students,” McCormick said. “I wanted to give students a way to connect what they’ve been learning in the classroom to public-health practice.”

A two-week trek

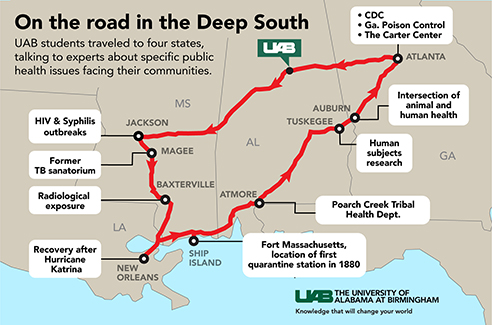

McCormick wanted to give UAB students the opportunity to lay eyes on public health disparities — something relatively easy to do in the poverty-stricken areas of the Southeast. So the group traveled to Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia and learned about everything from radiological exposure in rural townships to human subject research in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.

McCormick knows many students have dreams of working in global health in underdeveloped or developing countries, but she wanted them to see rural communities facing similar public health issues that are fairly close to Birmingham.

“You don’t have to leave the country to make a tremendous impact,” she said. “There are places not too far from our School of Public Health where we need public-health practitioners working to solve critical issues in our communities. I want to open students’ eyes to the options.”

|

Students catalogued their experiences on a blog, “Blazing the Trail: UAB Exploring Population Health,” in English and Spanish. |

During a two-week span, the group visited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, plus the Mississippi State Department of Health, the City of New Orleans Health Department, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Health Department in Atmore, Alabama, and the Escambia County Health Department in Brewton, Alabama.

“I wanted the students to see governmental public health at all levels — federal, state and local levels, urban versus rural, working with a tribal population versus working with the general population,” McCormick said.

They also visited a former tuberculosis sanatorium in Magee, Mississippi, and talked about the effects of microplastics in the ocean on sea life on Ship Island, Mississippi, among other places.

Click through the slideshow below to get a glimpse into the students’ experiences on their trip across the Southeast. Then, continue reading below.

-

The Mississippi State Sanitorium in Magee, Mississippi, originally opened in 1918 to fight tuberculosis in the state. It closed in 1976. The Mississippi State Sanitarium Museum features a reconstruction of the kind of room in which a tuberculosis patient would have been housed.

-

The State Sanitorium had its own dairy farm, generated its own power and operated its own post office.

-

In 1964, the U.S. government detonated an underground nuclear device outside Baxterville, Mississippi. This test, and another in the same location two years later, were the only nuclear explosions to happen east of the Rocky Mountain series. The ground near the site was too rough for the UAB group’s bus, so they transferred to a truck.

-

The Daughters of Charity have provided community health care in New Orleans for nearly 200 years, with 10 health centers located in the Algiers, Bywater, Carrollton, Gentilly, Gretna, Kenner, Louisa, Metairie, New Orleans East and Prytania neighborhoods.

-

A child’s toy teddy bear rescued from the Hurricane Katrina wreckage on display at the Louisiana State Museum.

-

he Doullut steamboat houses were built in 1905 and 1913 by riverboat pilot captain Milton Doullut on the highest land in the neighborhood. The interiors are coated with ceramic tile to prevent flood damage.

-

Students sifted sands on Mississippi’s Ship Island for microplastic litter.

-

The Poarch Creek Indian reservation in Atmore, Alabama, home to approximately 2,900 tribal members, has its own health department.

-

The UAB team visited the Escambia County Health Department in Brewton, Alabama.

-

The Rosenwald School in Tuskegee, Alabama, and its next-door neighbor, the Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church, were gathering points for Tuskegee Syphilis Study subjects for testing. Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish-American clothier who later became part-owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., partnered with Tuskegee Institute President Booker T. Washington to build more than 5,000 schools, shops and teachers homes across the United States, primarily for the education of Southern black children in the early 1900s.

-

While in Georgia, the group stopped by the Carter Center to meet with the managers of a Guinea worm eradication project. Guinea worm disease is a parasitic infection contracted when people consume water from stagnant sources contaminated with worm larvae; when eradicated, it will be the second human disease, after smallpox, to be eliminated.

-

At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, student Courtney Barkley tried on a biosafety suit.

-

The group stopped by the 128-year-old Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, the state’s largest Level I Trauma Center.

Lisa McCormick, Ph.D.,associate professor in the department of environmental health sciences and the associate dean for public health practice

Lisa McCormick, Ph.D.,associate professor in the department of environmental health sciences and the associate dean for public health practice

Looking toward the future

McCormick was the recipient of an Innovative Teaching and Development Grant focused on learning in a team environment, funded through a partnership between the UAB Center for Teaching and Learning and UAB’s Quality Enhancement Plan.

She plans to continue hosting trips in the future, and plans to take students in May 2019 to Panama City, famous for the public health work there in the early 1900s, when Alabamian W.C. Gorgas and his team of sanitation engineers drastically reduced yellow fever and malaria cases in Panama after implementing drainage systems, brush and grass cutting schedules and screening of buildings to keep out mosquitos.

“We’ll continue to look at the major themes, such as population health, social determinants of health and advancing health equity,” McCormick said. She plans to alternate the trips between international and domestic locations each year.

McCormick also wants to see students from more disciplines participate.

|

McCormick was the recipient of an Innovative Teaching and Development Grant focused on learning in a team environment, funded through a partnership between the UAB Center for Teaching and Learning and UAB’s Quality Enhancement Plan. |

“When you think about social determinants of health and how to solve complex public health issues in communities, it takes people from education, from engineering, to build more resilient communities that can better deal with adversities such as natural disasters and disease outbreak,” she said. “All those things go into making communities healthier.”

Claire Auriemma, a public health student whose eyes also were opened during the trip, agrees: It takes all disciplines to solve a public health crisis.

“Residents of the Lower Ninth Ward are left with an average life expectancy of 55 years,” she said. “That was an eye-opening, clear picture of health disparities for me, and while it was hard to witness, I needed to see it to understand.

“We have to work with policy-makers, educators, medical professionals,” Auriemma added. “We have to work with local businesses, religious leaders, community organizations and more to advance health equity and decrease health disparities. At every single stop, it was reinforced that collaboration is the core of advancing public health practice.”