Maggie AmslerIn Antarctica, the ice stretches frozen and glittering, cold and formidable, over the bottom of the world. Where it allows, divers travel by inflatable boat to a natural entry point; where it doesn’t, they slip into the water, below freezing even in the summer months, through manmade holes chiseled by chainsaws.

Maggie AmslerIn Antarctica, the ice stretches frozen and glittering, cold and formidable, over the bottom of the world. Where it allows, divers travel by inflatable boat to a natural entry point; where it doesn’t, they slip into the water, below freezing even in the summer months, through manmade holes chiseled by chainsaws.

There are no cities or towns or ancient manmade structures. Antarctica has no indigenous human population. Only about 1 percent of its land is exposed, the rest covered by a thick skin of snow and ice. It is home to seals and penguins and Antarctic petrels, a bird named for St. Peter, whose faith let him walk on water, because they run on top of the water as they take flight. The continent has only two species of flowering plant.

|

“Even a bad day here becomes instantly incredible with a look or walk outside.” |

But to Maggie Amsler, the continent also is intensely beautiful, despite its remoteness and constant cold. And Amsler would know — the benthic ecologist has trekked to the ice as a researcher 27 times in 35 years, studying everything from its krill population to the effects of ocean acidification on calcifying organisms. She is there now with a team from UAB on a 16-week expedition as a research associate at Palmer Station on Anvers Island, a U.S. Antarctic research center that clings to the northwest edge of the continent.

Many look and see the things that are not in this icy wilderness. But Amsler sees the footprints of her mentor, the arc of her career, a map dot with her name, a sometimes-home for a quasi-family, the future of the planet — and its magic.

“A simple act like traversing the walkway between buildings might include unique lighting on the glacier, a rare glimpse of nacreous clouds or a wayward emperor penguin,” Amsler said. “Even a bad day here becomes instantly incredible with a look or walk outside.”

|

“I thought in 1992, when I ‘retired,’ that I would never return to Palmer or Antarctica. Little did I know what the future would bring.” |

A change of plans

In her 20s, Maggie Amsler dreamed of the Caribbean. She dove weekly as a volunteer at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium coral reef tank, which at 90,000 gallons was then the world’s largest.

She said her career in Antarctica was chosen for her — with “no regrets,” she’s sure to add — by her advisor, mentor, renowned biologist and DePaul University Professor Mary Alice McWhinnie, Ph.D.

In 1974, McWhinnie became the first woman chief scientist at McMurdo Station, situated on the south tip of Ross Island on the continent’s northeast coast. That season, she and Sister Mary Odile Cahoon, an American Benedictine nun who also was among the first women researchers in Antarctica, were the first women to winter on the continent. McWhinnie also conducted research at Palmer Station, and the lab there is named for her.

Amsler working in the aquarium at Palmer StationWhile studying marine biology at DePaul, Amsler accompanied McWhinnie’s team to Palmer Station. She didn’t know it at the time, she says, but she was unwittingly changing the course of her career.

Amsler working in the aquarium at Palmer StationWhile studying marine biology at DePaul, Amsler accompanied McWhinnie’s team to Palmer Station. She didn’t know it at the time, she says, but she was unwittingly changing the course of her career.

“I knew long before college I wanted to pursue a career in marine biology, but polar marine biology was surely not on my radar until Dr. [McWhinnie] was assigned as my advisor,” Amsler said. “I never would have imagined that what I thought was a one-off season on the ice would turn into not only a career, but a passion.”

Building a career

After graduating from DePaul and earning her master’s degree at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, Amsler relocated to the University of California Santa Barbara with her husband and fellow researcher Chuck Amsler, Ph.D., now a UAB professor and Antarctic researcher.

During her first 12 trips to the continent, Amsler’s research mirrored her mentor’s: She studied krill, a small, cold-water relative of the crayfish and the basis of the Antarctic oceanic food web.

Amsler had her own firsts in Antarctica: In 1985, she was aboard the icebreaker research vessel Polar Duke on the first winter cruise along the peninsula while working with researchers from UC Santa Barbara.

|

“I never would have imagined that what I thought was a one-off season on the ice would turn into not only a career, but a passion.” |

Amsler retired from what she calls her “krill career” in 1992 to put down roots with her husband in Alabama, who joined UAB in 1994. She began working at UAB in 1996, and in 2001 she was back in Antarctica with a research team.

“I thought in 1992, when I ‘retired,’ that I would never return to Palmer or Antarctica,” Amsler said. “Little did I know what the future would bring.”

Since that 2001 trip, she and her husband, along with Jim McClintock, Ph.D., Endowed University Professor of Polar and Marine Biology, have studied the chemical defenses of marine plants and animals, the effects of ocean acidification on calcifying organisms and the movement of deep-sea crabs into shallow waters as a consequence of ocean warming.

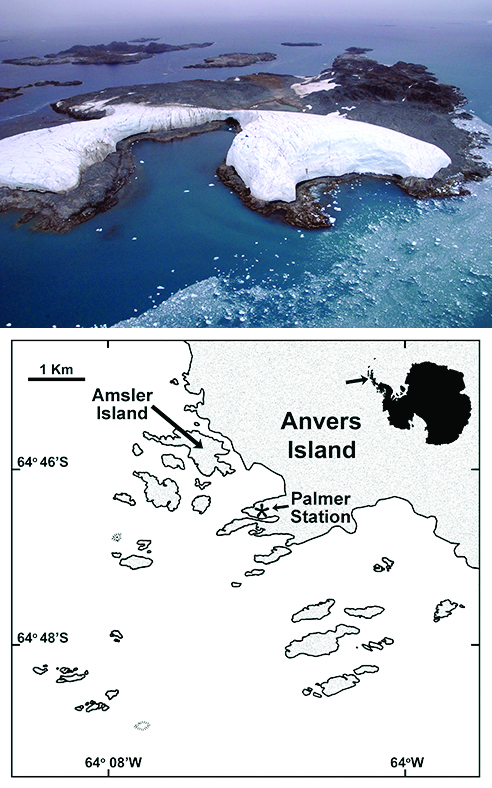

In 2007, she and Chuck were honored by the U.S. Board of Geographic names with the designation of Amsler Island, located about half a mile from Palmer Station. In 2017, Amsler sailed on one of the first cruises using submarines to document seafloor communities in Antarctica, and it’s likely she was the first woman ever to make a submersible dive there.

Amsler (left) with her husband, UAB Professor Chuck Amsler, Ph.D.

Amsler (left) with her husband, UAB Professor Chuck Amsler, Ph.D.

New chapter, new millennium

When Amsler and the UAB team arrived at Palmer Station aboard the Laurence M. Gould on Halloween night in 2001, it had been almost a decade since her last trip. The station had planned a Halloween costume party — Amsler planned to dress as a mermaid — but, a thick layer of ice covering the harbor surface prevented docking, so the team headed a day’s sail north to deliver passengers and ornithologists to a nearby field camp — “a tiny outpost where penguins outnumbered people,” Amsler said.

It would be days before the Gould could break through the ice and dock and weeks before the UAB team could traverse the area around Palmer Station in inflatable boats. Instead, they walked — Amsler and other divers dressed in drysuits to keep warm in the freezing water and their dive tenders hauled gear-laden sleds onto the ice-covered water.

They dove through manmade holes to collect invertebrates and seaweed for lab experiments. A line with a blinking light attached was lowered into the water to help divers find the exit when they were done.

Amsler says her first post-retirement trip to Antarctica with the UAB team was “magical” — especially her first dive that year into Hero Inlet along the south side of Palmer Station between Gamage and Bonaparte points. Visibility was so good, Amsler said, they didn’t even need the artificial light they’d lowered.

About 400 of her 800 total dives in her career have been in Antarctica.

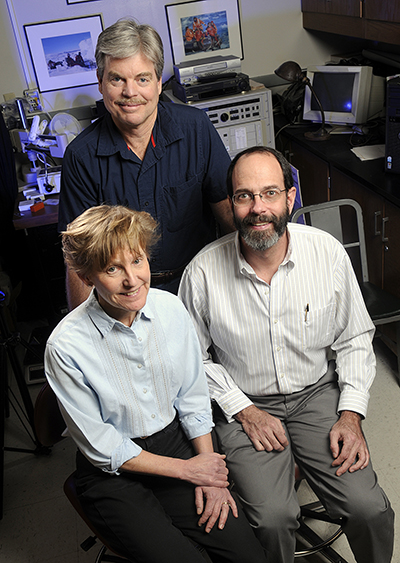

Amsler (left) with Chuck (right) and Jim McClintock, Ph.D., Endowed University Professor of Polar and Marine Biology (top)

Amsler (left) with Chuck (right) and Jim McClintock, Ph.D., Endowed University Professor of Polar and Marine Biology (top)

“At the bottom — all of 30 feet — I could see the rock walls lining both sides of the inlet and the icy wall of the glacier at the back end, at least three football fields away,” she said. “I felt as though I were in one of those infinitely long flat-roofed warehouses — the ice overhead was a crystal white and blue ceiling.”

First-person view

When Amsler had visited Antarctica in 1992, the glacier loomed over Palmer Station. A decade later, she was struck by just how much the environment had changed — and not for the better.

“The buildings had some minor improvements, but the glacier and the harbor were so mind-bogglingly, dramatically different. The glacier was so far away from the station. Where did it go in just 10 years? Over the 10-plus years I had been at the station as a krill biologist, the glacier face had never so obviously changed. The harbor had much more surface area than it used to as a consequence,” she said. “Glaciers should not move so obviously in a decade.”

|

“What happens in Antarctica and the Arctic matters and affects what happens in your hometown, your backyard, your children’s lives and your grandchildren’s lives.” |

More than almost any other human, Amsler personally has seen the extreme changes in Antarctica as the warming climate changes the face of the continent she has intermittently called home since 1980. She summarizes her feelings about them in one word: “dismayed.”

The evidence is ample: Glaciers are moving more quickly. Due to rocky ground created by glacier recession and a longer growing season spurred by more moderate temperatures, the Antarctic Peninsula is becoming greener as its two native plants and mosses have more bandwidth for growth. Krill shortages from a lack of winter sea ice mean annual crashes in seabird populations. On Amsler’s current trip, the station has been pummeled by 30- to 60-knot winds — about 35-70 miles per hour — hours on end for nearly a week, bringing “nasty combinations of rain-snow,” she said.

“The list of first-hand observations goes on, but all circle around to warming temperatures as the bottom line,” she continued. “Analytically, the numbers clearly show warming of the air and sea water is real. Meteorological data clearly shows increased frequency of rain events. It’s real. I’ve seen it with my own eyes.”

|

“It’s impossible for me not to be constantly amazed by Antarctica,” she said. “It is an environment that is ever-changing, despite its many constants, like cold, remoteness, raw beauty. I guess what continues to surprise me is how much I still don’t know about it.” |

Forming a family

During the 2001 trip, when most of the UAB team traveled home just before Christmas, Amsler remained at Palmer with a graduate student to finish experiments and pack. They missed loved ones over the holidays, but in a way, Amsler said, “Palmer itself represents home and family. A special place in that way.”

For Amsler, this is especially true. Unlike her days spent researching krill, Amsler now spends her expeditions in Antarctica with her husband.

“Life at Palmer is really awesome, but I can say that as one of few on the entire continent sharing each day with their spouse,” she said. “It was much harder and psychologically wearing in my krill days when Chuck was home with no concept of what daily life here was like.

“Palmer is typically perceived by our loved ones in the lonely routine back home as wondrous days of fun-filled adventures,” she said, “and for many here, that conundrum taxes the psyche and the heart as it did me for much of the krill years.”

The teams at Palmer often travel by inflatable boat, like the one Amsler is riding.To get through the tough days in the Antarctic, Palmer Station teams have formed kinds of quasi-families, born and held together by and through not only necessity, but determination and grit and a passion for the cold, rocky, indomitable continent they from time to time call home. Amsler calls them “Palmerites,” and said she often reminisces about them during her time at the station.

The teams at Palmer often travel by inflatable boat, like the one Amsler is riding.To get through the tough days in the Antarctic, Palmer Station teams have formed kinds of quasi-families, born and held together by and through not only necessity, but determination and grit and a passion for the cold, rocky, indomitable continent they from time to time call home. Amsler calls them “Palmerites,” and said she often reminisces about them during her time at the station.

“Over the years, most have moved on, but I often see or am somehow reminded of them,” she said. “Their spirits live in the hallways of Palmer.”

Spirit of a pioneer

The lab at Palmer Station is named for Amsler’s mentor McWhinnie, who has been one of her biggest inspirations — and who, even after her death in 1980, is present in the station.

“I silently say thank you each time I walk by her portrait in the lab hallway,” she said. “I will never approach her accomplishments as a scientist, an international diplomat, Antarctic conservationist — and, of course, an ice-ceiling-shattering female.”

Amsler said neither McWhinnie nor any other woman scientist who mentored her ever gave her any particular spoken advice, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t teach her important lessons. She learned to try to keep with what she calls the spirit of Antarctica, which can be summed up in the motto engraved on the U.S. Antarctic Service medal: “courage, sacrifice, devotion.”

|

"I’ve learned that as tough as nails as I want to be and project myself to be, that I am just me. Just a person trying to do the best and contribute as best I can.” |

“Three words to honor at any latitude,” Amsler said, “especially when accompanied with diplomatic grace and geniality.”

Amsler with McWinnie's portrait in the Palmer biolab

Amsler with McWinnie's portrait in the Palmer biolab

To do that, she must be both self-sufficient and self-reliant while still remaining a team player — a trait she learned from McWhinnie, who earned her successes at McMurdo Station as a pioneer for women scientists. A few years ago, Amsler corresponded with a few men who had worked at McMurdo and with McWhinnie.

“One wrote of how Dr. [McWhinnie] was commonly positively described among the men there in the vernacular of the time,” Amsler said. “’She ain’t a bad broad.’

“In the late 1960s and early ’70s, given her gender and academic status, declarations like that spoke volumes and still do today.”

Amsler works all year to stay fit enough for the field; if she can’t do the physical labor, she shouldn’t take the trip. She wants to continue to carry more than her weight there, despite the decades that have passed since she began making the trek, and she has learned more than a bit about herself along the way.

“I’ve learned that as tough as nails as I want to be and project myself to be, that I am just me,” she said. “Just a person trying to do the best and contribute as best I can.”

Amsler Island (top, seen from above), named for Amsler and her husband in 2007, is located near Palmer Station

Amsler Island (top, seen from above), named for Amsler and her husband in 2007, is located near Palmer Station

Keeping the faith

In 2015, the British Antarctic Survey published the results of a 50-year survey. The Antarctic giant petrel on the small subantarctic island of Signy, about 700 miles northwest of Palmer Station, has experienced a 50-percent population decline in the past 10-20 years, potentially due to a reduction in sea ice or other factors affecting food availability. Although the population increased from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s, it has halved from more than 5,800 birds to around 2,600 since 2005.

“Because the South Orkney Islands, of which Signy is a part, represent nearly 10 percent of the global population of this species, continuation of such a decline both at Signy and elsewhere in this island group would be of conservation concern,” wrote the paper’s lead author.

|

“I silently say thank you each time I walk by [McWhinnie's] portrait in the lab hallway. I will never approach her accomplishments as a scientist, an international diplomat, Antarctic conservationist — and, of course, an ice-ceiling-shattering female.” |

Though their numbers decrease, the petrels remain solely Antarctic birds. Maybe, like their namesake, they have a kind of faith in the continent that, despite its changes, still enables their survival.

Amsler, too, still has faith in Antarctica. It’s why she continues to return to do research, even as the years and decades pass.

“It’s impossible for me not to be constantly amazed by Antarctica,” she said. “It is an environment that is ever-changing, despite its many constants, like cold, remoteness, raw beauty. I guess what continues to surprise me is how much I still don’t know about it.”

But she does know one thing that pushes her to do more research, teach more conservation and keep traveling to a continent that is shifting and changing around her:

“What happens in Antarctica and the Arctic matters and affects what happens in your hometown, your backyard, your children’s lives and your grandchildren’s lives.”