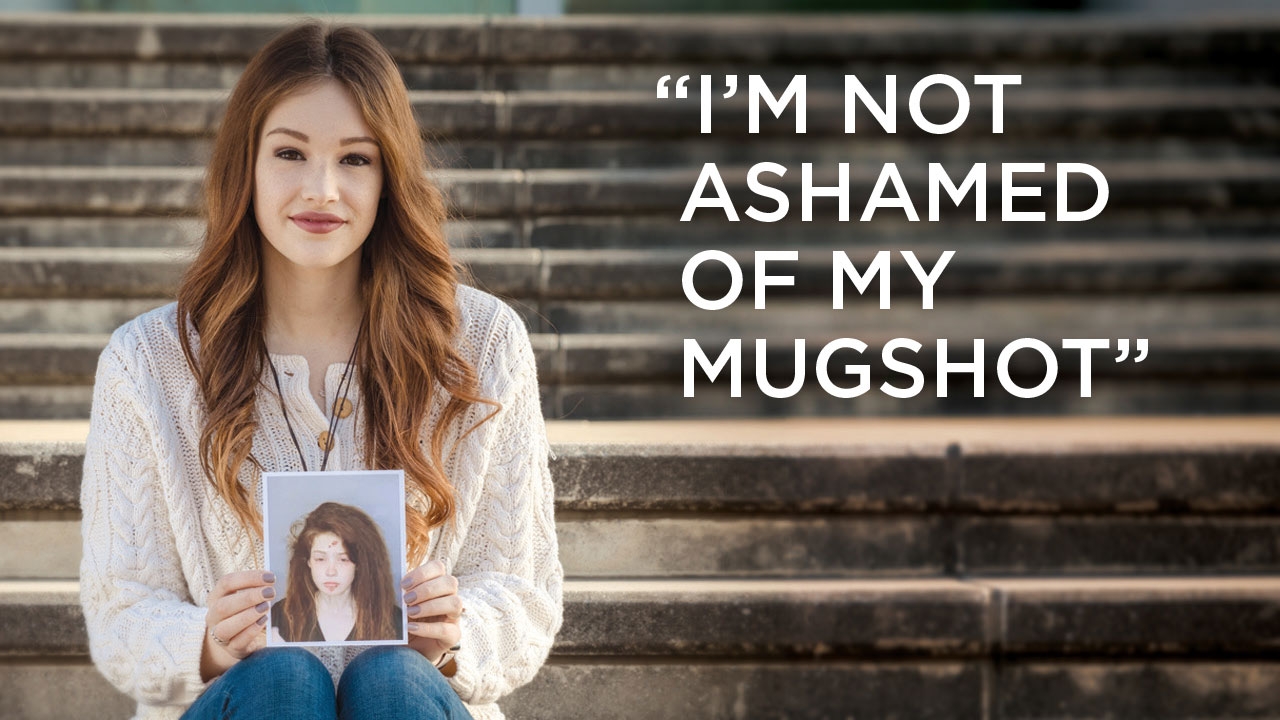

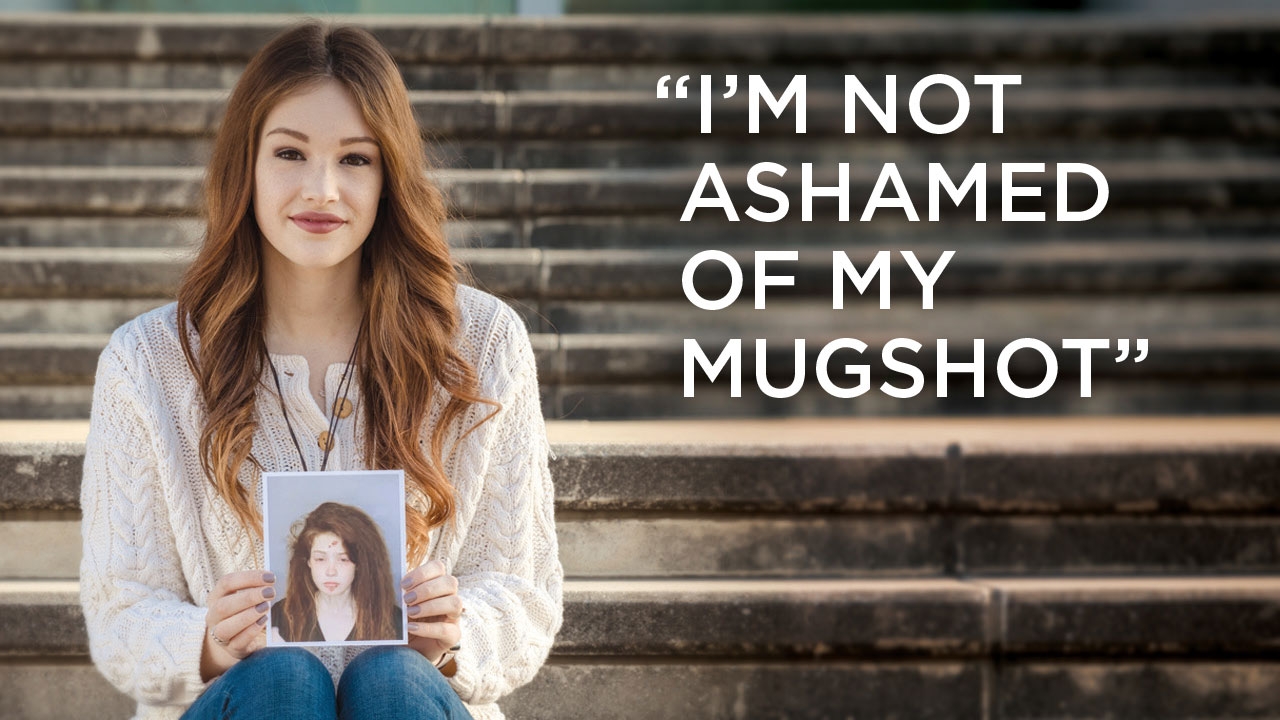

Last year Anna Alford lost five friends to overdoses. Among them, her boyfriend Drew. “He had been sober, but used one time and died,” she says. When she heard the news, Alford (pictured above) was attending a recovery conference herself.

Her story begins at age 14, when the Memphis native tried marijuana. Soon she was addicted to bath salts, Xanax, and Lortab. “I loved changing the way I felt through drugs,” Alford says. She got expelled from school, spent graduation money to crush and snort Roxicodone pills, sneaked heroin into hospitals to shoot it from her bed, lived in her mother’s car, and got arrested for heroin possession. “I was raised by a wealthy family and went to a private high school,” Alford says. “Being in jail was hard.”

Her mother brought her to one more rehabilitation center. “I had no intention of staying sober, but something came over me,” Alford says. “I surrendered.” Since February 2016, she has committed to a recovery program, using tools such as 12-step fellowships. She enrolled at UAB, and lives and works at Fourth Dimension, a Birmingham sober-living facility.

“Recovery is my whole life now,” says the social work major, a junior who plans a career helping others following her same path. With her mugshot in hand, she speaks openly about her journey to decrease stigma around addiction. “I want to give people hope,” she says.

•••

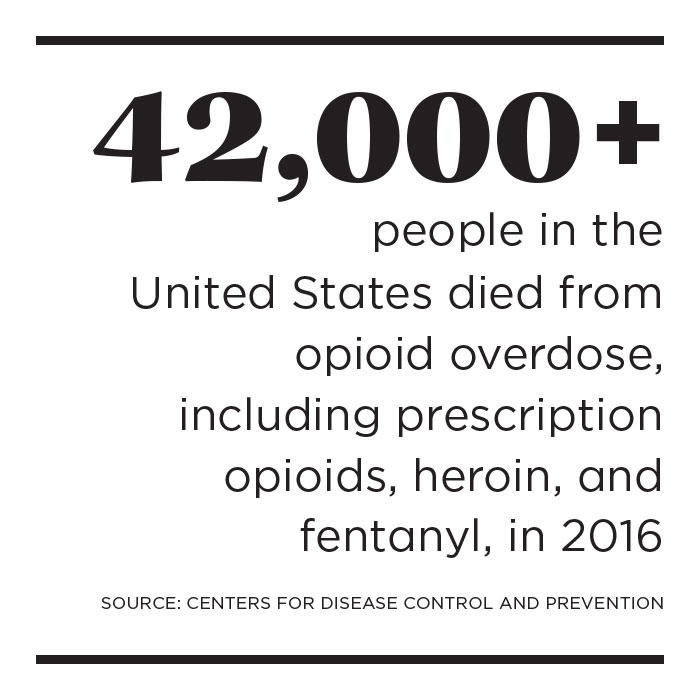

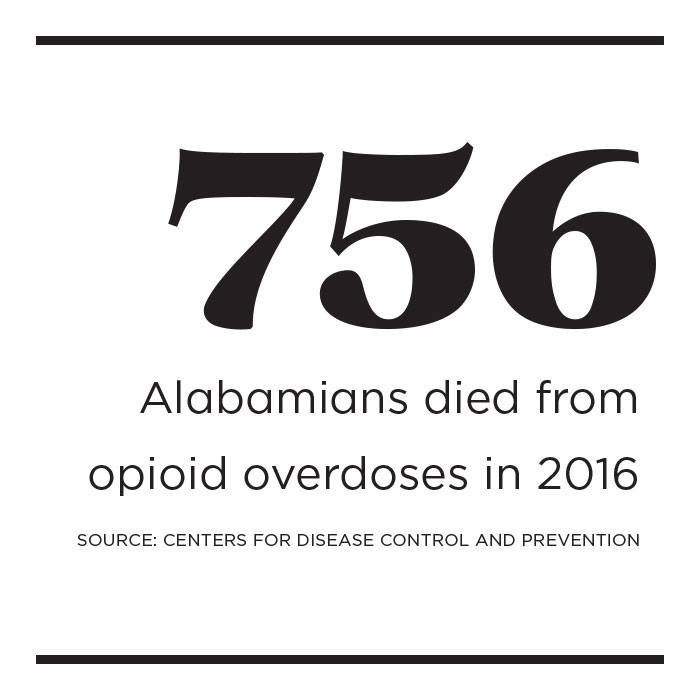

The headlines repeat in an endless stream: Drug overdoses are the leading cause of death among Americans under 50. They kill more people than guns or car accidents. They have caused life expectancy in the United States to decrease for the second consecutive year.

At the heart of the issue: a spike in deaths from opioids, the class of pain-relieving drugs that includes some available by prescription—OxyContin (containing oxycodone), Vicodin (containing hydrocodone), morphine, and others—plus heroin and powerful, illegally manufactured synthetic drugs like fentanyl. All work by interacting with specific opioid receptors on nerve cells in the body and brain.

Opioid addiction can happen to anyone, “even sorority girls like me,” Alford says. While rural areas have been hit hard, opioid misuse impacts every community and crosses economic and racial lines. There is no one solution—or any simple solutions—for this complex national public health crisis. But every day, UAB faculty, staff, and students are finding answers that point to a clearer path for people suffering from addiction. Meet a few leading the charge to save lives.

Stefan Kertesz encourages a big-picture approach to the crisis that is sensitive to patients and addresses illicit opioids outside medical care. Photo by Dustin Massey.

Stefan Kertesz encourages a big-picture approach to the crisis that is sensitive to patients and addresses illicit opioids outside medical care. Photo by Dustin Massey.“Prescriptions are going down, but overdose deaths are going up.”

The overprescription of opioid pills from the 1980s through the early 2000s helped light the current wildfire, but that is only one piece of the long, complicated timeline of the opioid crisis, says Stefan Kertesz, M.D. Working with disadvantaged populations inspired Kertesz, a School of Medicine professor of preventive medicine, to study substance abuse disorders. His analysis of the evolving opioid response has resonated nationally, and he frequently helps colleagues navigate policy and care.

Opioids have been used in America for nearly two centuries, but two decades of easy access led some people to become unwittingly addicted to the painkillers following medical procedures; others used the drugs recreationally. That sparked an illegal trade that found fertile ground in economically distressed regions where users turned to the drugs to numb pain—both physical and emotional—and generate income.

Policies to reduce overprescription have complicated matters for physicians and patients. After all, opioids are necessary for treating certain types of pain. Kertesz advises medical teams to prescribe cautiously and monitor patients at risk for addiction. It can be a tricky line to draw, taking into account factors such as family history, previous drug use, anxiety and depression, and past trauma, Kertesz says. Medical providers also should closely evaluate the patient’s response and develop a plan to wean the patient from the drug as appropriate. Most people taking longer-term opioids will develop physical dependence, which can be managed medically, Kertesz says. “The danger comes when physical dependence crosses into addiction,” a disease characterized by uncontrollable cravings.

Beyond the doctor’s office, the decrease in prescriptions has not led to fewer deaths, in part because heroin and fentanyl are abundant and inexpensive, Kertesz says. (In 2016, those two drugs accounted for nearly all overdose deaths in Jefferson County.)

More federal and state funding for research and treatment would help. Congress approved $1 billion to combat the opioid crisis (via the 21st Century Cures Act), but Kertesz says that is only a drop in the bucket. “This will require tens of billions of dollars.”

Then there’s a tougher problem: the underlying social and economic causes that can lead someone to seek relief in drugs. Kertesz says civic organizations of all types can play a role in creating a sense of belonging. “Lack of hope, opportunity, connection, and community increase a person’s chance of seeking an escape.”

"We need to do a better job meeting people with addiction where they are.”

The opioid crisis has shaped the way Cayce Paddock, M.D., cares for patients. “I spend a lot of time listening to their stories,” says the director of the Division of Addiction Psychiatry. “In general, people don’t begin to use drugs for no reason.” She looks for signs of mental health issues, including depression and anxiety, and trauma. “Once we wash away the substance, so to speak, we can tackle what’s underneath.”

That personalized approach is critical considering the swift progression of opioid use into a chronic disease. Some people can take medically prescribed opioids for a short time without encountering issues. But after 28 days, the chance of physical dependence greatly increases. Many factors—genetic, physical, psychological, environmental—affect addiction risk for any drug. But with opioids, the availability of cheap synthetics like fentanyl can prompt a quick shift from pill to needle, raising the risk of blood-borne illnesses and potentially deadly conditions like endocarditis, an inflammation of the heart’s inner lining.

UAB Medicine’s Addiction Recovery Program, led by Peter Lane, D.O., and Paddock, includes a detox unit, residential and outpatient services, and a consultation service for UAB medical providers. The 90-day treatment program provides a medically supervised approach to early sobriety, including intensive therapy, 12-step fellowship, trauma and grief work, and family support, with the goal of breaking the addiction cycle. Many with opioid use disorder leave with some form of medication assisted therapy (MAT), along with access to a two-year aftercare program. The team also has begun training medical staff throughout the hospital—physicians, nurses, therapists, social workers, and others—to better care for patients with addiction anywhere they require care.

Recovery is possible, Paddock emphasizes. “Some of the most psychologically and emotionally healthy people I know are in recovery from a substance abuse disorder. When I see someone in active addiction, I see them at their lowest. But they can live and thrive. When I meet people in active addiction, I see them as they can be, not as they are in that moment.”

“A sick brain influences decisions. We can provide tools that give people a fighting chance to get well.”

Each person follows a unique journey from addiction to recovery. But for many, medication assisted therapy (MAT) offers some breathing room, says School of Nursing professor Susanne Fogger, D.N.P. With more than 35 years of experience in psychiatric/mental health nursing, Fogger has seen the impact of MAT. “These medicines give us time to help patients learn to function in the world,” she says.

The therapies normalize brain chemistry, block the abused drug’s euphoric effects, relieve physiological cravings, and readjust body functions. Some medicines, such as methadone, buprenorphine (Subutex), or burenorphine plus naloxone (Suboxone), minimize withdrawal symptoms. Vivitrol is a long-acting naloxone that blocks the effects of opioids. Data shows that MAT, often prescribed with counseling, behavioral therapy, and a program of care, can decrease opioid use, opioid-related overdose deaths, criminal activity, and infectious disease transmission.

“We don’t know how big the problem is. Overdoses and deaths are the tip of the iceberg.”

Nearly every day, James Galbraith, M.D., associate professor of emergency medicine, treats patients who have overdosed or suffer from the effects of addiction. But that may not be the only medical challenge they face. In 2015, Galbraith and his team began screening every UAB emergency patient for hepatitis C, a potentially fatal liver disease that may not present symptoms, and connecting those with positive results to appropriate care. An increase in cases among people under 30 is linked with intravenous drug use—specifically opioids—Galbraith says. Now he is monitoring data indicating that central Alabama may be on the verge of a significant HIV outbreak linked to IV drug use.

Galbraith believes syringe exchange programs could help reduce the spread of blood-borne illnesses by providing IV users with clean needles in a medically monitored environment. Participants would also have access to hepatitis C and HIV screenings and receive naloxone kits and treatment information. Safe disposal bins would help clear used needles from the streets.

The Alabama Legislature is considering a bill to legalize syringe services, which Galbraith calls “politically controversial, but not scientifically controversial.” The approach may appear counterintuitive, he says, noting that “10 years ago, I would not have understood the necessity or benefits of needle exchanges.” But “the escalating local syndemic of opioid injection and hepatitis C infection has driven me to seek all possible solutions, and needle exchanges are critical community interventions that have proven to be effective.”

Students who have embraced long-term recovery need support from one another and from their university communities in order to excel academically while staying healthy, says Luciana Silva, project manager for UAB's Collegiate Recovery Community.

Students who have embraced long-term recovery need support from one another and from their university communities in order to excel academically while staying healthy, says Luciana Silva, project manager for UAB's Collegiate Recovery Community.“We support people during a time that can be challenging to recovery: college.”

When Anna Alford arrived at UAB, Luciana Silva, Ph.D., LMFT, was ready to welcome her. She is project manager for the Collegiate Recovery Community (CRC), a program designed to help UAB students work toward long-term sobriety as they navigate college life. Opened in 2015, CRC assists students in recovery by offering a network and resources—among them, peer-led campus support groups, educational workshops, and service opportunities. The program also provides a safe place to study and socialize, hosting activities such as weekly dinners, holiday celebrations, and Sober Spring Break. CRC’s ultimate goal is to establish a foundation students can build upon long after they graduate, Silva says.

Most participants have a history with opioids, says former CRC assistant Taylor Milam. That includes Milam himself, whose experience as an undergraduate helped shape the program. “Students come to CRC from many paths,” says the social work major. “The important thing is that they are all committed to recovery.”

“A majority of people use the kits to save someone else.”

Alabama pharmacies can dispense naloxone, or Narcan, a medicine to reverse overdose, without a prescription. But the cost can be prohibitive. So Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., turned to the Internet. Through a UAB crowdfunding platform (now called FIRE), Cropsey, the Vivian Conatser Turner Endowed Professor in Psychiatry, raised $11,500 for a study providing more than 350 naloxone kits to opioid users and their families. Recipients also were trained to spot overdoses, administer medication, and call 911 for critical follow-up care.

At least 28 kits have been used, mostly by loved ones, and several recipients now live in recovery. “I received an email from a person who said, ‘Your study saved my life,’” Cropsey says. “Today 28 people are still alive, surrounded by people who care for them.”

A second crowdfunding campaign earned $3,500 for kits for people living in rural areas around Walker County. “These kits buy vital time” for them, Cropsey explains. “It can take 20 minutes to get to the hospital.” Next, Cropsey wants to make Narcan available to newly released prisoners. “We don’t want people to abuse opioids, but the reality is they do,” she says. “I’m interested in saving lives and gathering research to better care for this population.”

“It’s a cultural thing that Americans expect a pill for every symptom.”

Mark Bailey, D.O., Ph.D., treats patients with severe, chronic pain from conditions including back and neck issues, multiple sclerosis, and trauma. For many of them, opioids are essential to treatment. But Bailey, like other physicians, is rethinking his approach to pain. “The United States consumes 80 percent of the world’s narcotics,” says the neurology professor, part of the Federation of State Medical Boards panel that updated opioid use guidelines followed nationwide. “Do we hurt more than other places? I don’t think so.”

Providing care patients need while preventing dependence and navigating new regulations is challenging, Bailey says. But he helps patients—including some who have taken prescribed opioids for 20 years—taper to lower recommended doses. “They are doing quite well,” he says. He also works with them to relieve pain through exercise, behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and other methods.

Though state and federal guidelines endorse these promising therapies, insurance often doesn’t cover them—or newer opioid formulations that discourage misuse, like tamper-resistant drugs. That limits their use, Bailey says. “They’re not an option for many of my patients financially. It’s a tough time to be a pain doctor or a pain patient.”

Cayce Paddock (left) helped Michael Grammas find a path to recovery—and the inspiration to support others in need.

Cayce Paddock (left) helped Michael Grammas find a path to recovery—and the inspiration to support others in need.

With substance abuse, “your intentions never match reality."

“Maybe there is a time when you could quit but don’t want to; then, when you want to quit, you can’t," recalls Michael Grammas. "At some point you lose your integrity, values, and character—the things that define us as people.” But as a patient in UAB’s Addiction Recovery Program under the care of Cayce Paddock, Grammas found help—physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual—from both peers and health professionals. “The recovery community at large is one of the greatest examples of humanity,” he says. “It’s broken people helping other broken people. You realize you aren’t alone, and there are solutions.” Inspired by his experiences in recovery, Grammas founded YANA, a Birmingham sober living community for men transitioning from inpatient care. “We must come together to help those with addiction, or else our families and communities will suffer the consequences of our self-imposed stigma,” he says.

“Some pain with a dental procedure is normal. But there are safe, effective options to reduce pain.”

A patient’s introduction to painkillers often happens after a minor dental surgical procedure—something the profession takes seriously, says Peter Waite, D.D.S., M.D., the Charles A. McCallum Chair of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in the School of Dentistry. “We have more frank conversations about addiction,” he says.

Now, Waite and his colleagues work to preempt pain by giving patients anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen or corticosteroids before procedures. And they listen closely. “Patients who are fearful and anxious will have more pain,” Waite says. “So we overcommunicate to let them know we will be gentle. Dentists are compassionate and conscientious.” On a national level, Michael Reddy, D.M.D., D.M.Sc., dean and the University of Alabama School of Dentistry Alumni Association Endowed Professor, and Nico Geurs, D.D.S., periodontology chair and the Dr. Tommy Weatherford/Dr. Kent Palcanis Endowed Professor, are part of an American Dental Education Association council that is improving training on pain management and addiction among students and practitioners.

UAB dental students study pain, anxiety, and pharmacology, and they learn to care for people in active addiction and recovery. Their training emphasizes best practices in pain management—such as dispensing small medication doses—and the complex factors to consider when prescribing. Two examples: UAB dentists take thorough patient histories, noting requests for specific painkillers, a possible sign of abuse. And they check the Alabama Prescription Drug Monitoring Program database to see who already has received potentially addictive medications.

“Recovery is not one size fits all.”

Many people arrested on drug charges in Jefferson County appear before a judge—and then someone like Bailey Davis. He works with the Department of Psychiatry’s Substance Abuse Programs, which oversees Treatment Alternatives for Safer Communities (TASC), the county’s community corrections program. Through the 45-year-old TASC, adult and adolescent offenders get help entering recovery and rebuilding their lives instead of jail time. “The judiciary, jails, and police officers see people dying and want to help,” says Davis, director of justice programs. “We work hand in hand with the legal system to determine the best approach according to each person.”

For instance, those in Jefferson County’s Drug Court receive individualized case plans addressing substance abuse, physical and psychological health, housing, vocational and social support, and other needs. They must pass drug screens, perform community service, pay fees, and attend classes through TASC. “We have a dialogue with clients to find out how we can best serve,” Davis says.

In the past three years, TASC staff have seen an increase in opioid-related drug arrests, with all other drug arrests (except amphetamine) decreasing, says John Dantzler, Ph.D., executive director of Substance Abuse Programs and its Beacon Addiction Treatment Center. “More couples come in arrested together. It is tearing families apart.”

“We see on a personal level the revolving door of addiction,” adds Debbi Sims, a former clinical director who had TASC clients with multiple incarcerations, chronic health issues, and economic instability. Compounding their challenges, most have no insurance, and state-funded detox and treatment programs typically have two- to three-week waiting lists. That extra time could prove deadly for someone needing immediate assistance, Sims says. Then there is the issue of paying for MAT to continue recovery.

Fortunately, money from the 21st Century Cures Act will help states expand treatment access and other opioid-related initiatives. In Birmingham, community partners including UAB are planning to open the Recovery Resource Center, a one-stop hub for addiction help available to everyone. “When you are in crisis, navigating the medical system is overwhelming,” says Suzanne Muir, Substance Abuse Programs associate director.

Dantzler hopes the new center will offer insights on next-generation practices for addiction medicine. “It’s incumbent on us to use our findings to develop better care,” he says.