BPR 45 | 2018

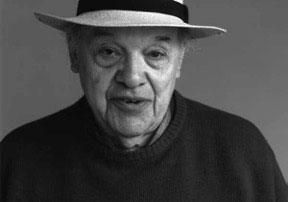

Excerpt (full interview available in Birmingham Poetry Review number 45 and as a downloadable pdf) When the qualities of Gerald Stern’s poetry are enumerated, political engagement typically makes the list, along with Jewish American themes, dark humor, long lines, irony, and ambivalent nostalgia. In interviews, Stern tends to mention his having made room in his poetry both for the political and for what he calls the aesthetic. For example, in a 2006 interview in the Bellingham Review, Stern explains that his attention to politics dates from his childhood. However, he continues,

When the qualities of Gerald Stern’s poetry are enumerated, political engagement typically makes the list, along with Jewish American themes, dark humor, long lines, irony, and ambivalent nostalgia. In interviews, Stern tends to mention his having made room in his poetry both for the political and for what he calls the aesthetic. For example, in a 2006 interview in the Bellingham Review, Stern explains that his attention to politics dates from his childhood. However, he continues,

When I got to be nineteen or so I started to get interested in something crazy called poetry. There were no books in my house, I never took an English course, I had no community. I moved away from the political and into the aesthetic, as I’ve talked about from time to time. And I put politics on the shelf for awhile while I pursued aesthetics, but then I came back to politics and I merged the two actually, and that’s where I am now.

What has that merging yielded? Or, to put it another way, where, exactly, has Stern’s merging of politics and aesthetics taken him—and his readers?

Stern’s political activism has included organizing civil rights marches in Pennsylvania during the 1960s, serving as president and chief negotiator of a New Jersey teachers’ union, and leading protests that led the Iowa state colleges to divest from South Africa during apartheid. Stern’s pursuit of this work alongside and within the poetic places him at a unique position in relation to the poetry being written and published in response to the current “political disaster” of Donald Trump’s presidency, as the title of a chapbook published in January 2017 by the Boston Review puts it. An April feature in The New York Times Book Review highlights an “emerging body of brash political poetry” and includes five poems “that speak to this moment in American politics and history.”

The influence of Stern’s approaches to poetry and politics can be read in much of this poetry. For example, the first of the protest poems in the Times feature, Alex Dimitrov’s “The Moon After Election Day,” begins, “I’m looking at the moon tonight, / the closest it’s been to Earth since 1948…” Dimitrov recalls Stern in his use of the continuous present tense (“I’m looking”), which suggests the beginning, or perhaps the middle, of a conversation more than it does the opening of a poem. Dimitrov, a younger poet whose second book was released in early 2017, echoes a poem from Stern’s first book, Rejoicings, “On the Far Edge of Kilmer,” which begins, “I am sitting again on the steps of the burned out barrack. / I come here, like Proust or Adam Kadmon, every night to watch the sun leave.” Both poems introduce their readers to an “I” who oscillates between specificity (1948, Proust) and generality (Earth, Adam Kadmon). Dimitrov cites 1948 not, I think, because of world or lunar events of that year, but to cast a shadow of nostalgia over the poem; Stern likewise peppers his poems with specific years; the titles alone of Stern’s 2005 American Sonnets, for instance, conjure “Aberdeen Proving Grounds, 1946,” “September, 1999,” and “1940 LaSalle” (Stern’s attention to car makes and models probably deserves an essay of its own).