The new Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts showcases works by students, professors and guest artists, but an area behind the building is an artful solution to an urban problem. A narrow trough, called a bioswale, between the rear of the building and the parking lot uses several layers of absorbent materials to prevent flooding in the area.

The feature helps raise the low absorbency rate typical for urban areas. In rural areas nearly 50 percent of stormwater is absorbed through the ground, but the rate is only 15 percent in urban areas.

"Stormwater from developed areas is the second highest source of surface, or drinking, water pollution in the United States," said Julie Price, UAB sustainability coordinator. "Essentially we put water straight from a parking lot into a river instead of letting it move through the ground."

Price said the expanse of impervious surfaces such as roads, parking lots and rooftops contribute to the rush of runoff that enters the stormwater system in urban areas.

“Birmingham and other urban areas in the United States have aging stormwater systems that are often overburdened during periods of heavy rainfall,” Price said. “These underground conveyance systems are massive, complex and expensive to construct and maintain.

The strain on the stormwater system results in flooding, especially around parking lots and buildings. Price said low-impact-development (LID) elements such as bioswales reduce pressure on the stormwater system by allowing some water to infiltrate into the ground and slowing the water that may eventually enter the system.

| Water can be managed in a way that reduces the impact of built areas and promotes the natural movement of water within an ecosystem or watershed. |

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, LID is an approach to land development that works with nature to manage stormwater as close to its source as possible.

“LID employs principles such as preserving and recreating natural landscape features, minimizing effective imperviousness to create functional and appealing site drainage that treat stormwater as a resource rather than a waste product,” the EPA states on its website. “By implementing LID principles and practices, water can be managed in a way that reduces the impact of built areas and promotes the natural movement of water within an ecosystem or watershed.”

"In cities, we convey runoff quickly into underground infrastructure to send out to a receiving creek or river," Price said. "LID elements such as bioswales reduce what goes into the stormwater system and instead allows some infiltration into the ground. This is the idea of treating rain as a resource — letting it infiltrate the ground, wherein it is filtered and doesn’t contribute to flooding — instead of a waste product that we consolidate into little tunnels and quickly convey out of the city with no infiltration to clean pollutants that have accumulated."

How bioswales work

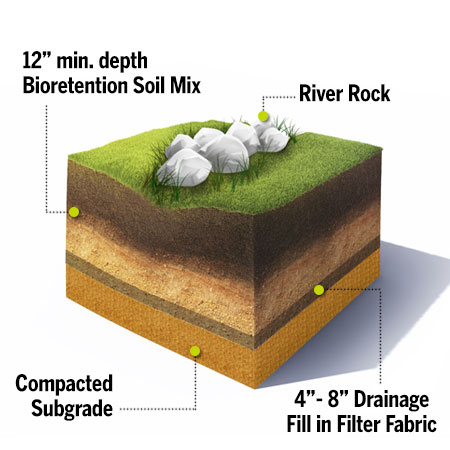

A bioswale is a long, narrow trough with gently sloped sides, which is filled with compacted subgrade, absorbent drainage fill, a special bioretention soil mix and river rocks. Each layer has a different absorption and release rate, which helps prevent oversaturation of the ground. The layers also work to filter silt and pollution from the runoff. The design is meant to maximize the time water spends in the bioswale, which helps trap pollutants and silt.

Bob Kruse, project manager in the Department of Project Management Services, said all stormwater from the parking lot behind the AEIVA flows into the bioswale.

“Bioswales are becoming more common in construction design around the country,” Kruse said. “At this time there’s not a lot of them, but we’re looking to adapt it where we can, according to the lay of the land, where’s it’s an acceptable and good practice.”

Kruse said one benefit to installing the bioswale is that it blends into the environment and looks like part of the landscaping.

“It’s a great way to control erosion and to control water runoff,” Kruse said. “And it gives you another green area instead of just another hard surface for the water to flow across.”

Sustainability at UAB

Price said design and construction teams must complete the UAB Sustainable Building Design Parameter Checklist for all new projects, including renovations.

“This checklist addresses everything from energy efficiency to construction-waste management,” Price said. “We also use the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED building rating system as a guide for many aspects of the projects. Certain projects are also particularly well-suited to new elements, such as bioswale.”

The bioswale is just one example of a LID, others include rain gardens, cisterns, green roofs and permeable pavement systems. Price said UAB Planning, Design and Construction considers LID elements as projects permit with regard to space and budget.

“In some cases, LID elements can reduce the need for traditional underground stormwater handling, which offsets the cost of the LID addition,” Price said.

Price said UAB is responsible for directing stormwater from major construction sites to the existing city stormwater infrastructure, which usually means the construction of underground channels or inlets.

"It's usually a lot of concrete and digging and can be very expensive," Price said. "The site is assessed by civil engineers and a design is drawn up for a conveyance system that can handle the amount of runoff from the site based on the square footage of the impervious surfaces and the typical storms we have in the region. The bioswale reduced the need for inlets and much of the conveyance."