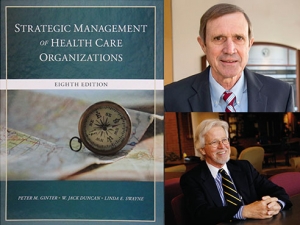

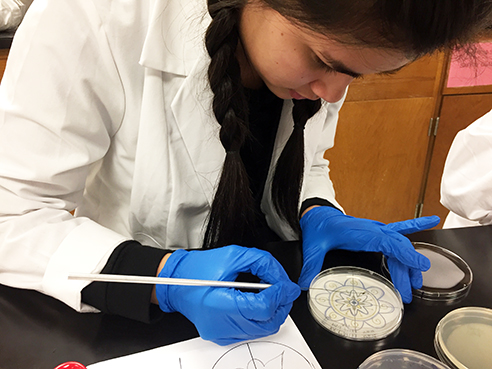

Biology doctoral student Sarah Adkins (top) and assistant professor of biology Jeff Morris, Ph.D. Sarah Adkins, a biology doctoral student and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow, believes the intersection of art and science is where innovation begins — and she’s got the colorful petri dishes to prove it.

Biology doctoral student Sarah Adkins (top) and assistant professor of biology Jeff Morris, Ph.D. Sarah Adkins, a biology doctoral student and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow, believes the intersection of art and science is where innovation begins — and she’s got the colorful petri dishes to prove it.

Adkins, who studied integrative biology and art studio as an undergraduate at UAB, worked with Assistant Professor Jeffrey Morris, Ph.D., to overhaul BY 271 — Biology of Microorganisms — into a combination art/science class in which undergraduates design artworks of bacteria in petri dishes.

The class illustrates a new approach to instruction and learning in a team environment — the key element of the university’s Quality Enhancement Plan — and Morris received a UAB Teaching Innovation and Development Award from the Center for Teaching and Learning to purchase new equipment, such as a camera to document the results.

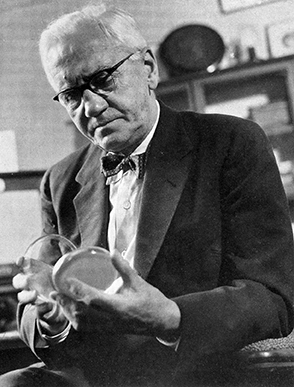

The process is relatively simple: The students dig up a handful of soil, usually from the UAB Mini Park across the street from the Campbell Hall lab, then dilute the soil and pipette it onto plates. Within several days, colonies of bacteria begin to grow — some colonies may be green, while others could be red, yellow or orange. Students then isolate each color onto its own plate to create a living palette for their art project.

Students paint a design of their own making on the petri dish with the colorful bacteria, observing how they interact with and react to one another.

Students paint a design of their own making on the petri dish with the colorful bacteria, observing how they interact with and react to one another.

Next the students paint a design of their own making on the petri dish with the colorful bacteria, observing how they interact with and react to one another. Certain combinations form a polka-dot pattern at their intersections; some bacteria destroy differently colored strains. The students observe, form hypotheses and draw conclusions about the behavior of bacteria.

“That’s what we do,” Morris said. “We have a collection of unexplained observances. That’s where science comes in — you’re trying to figure how to explain this stuff.”

The project gives undergraduates a unique research experience, Adkins and Morris said, and it also could have long-lasting implications.

“Many of the antibiotics we use come from soil bacteria,” Morris said. “Our students certainly see antibiotics in action, through evidence that one bacteria totally killed off another. Whether [those antibiotics] are new or poisonous to humans or useful at all, it’s hard to say at this point. Just discovering a new chemical backbone would be a huge thing.”

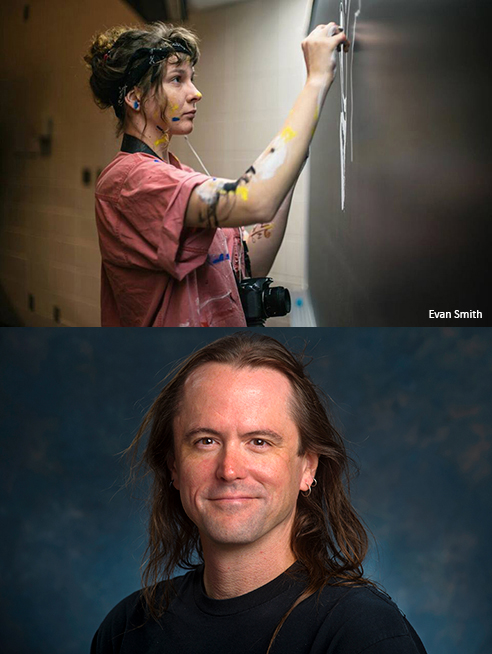

Sir Alexander Fleming, the Scottish biologist who discovered penicillin

Sir Alexander Fleming, the Scottish biologist who discovered penicillin

A colorful history

“For as long as people have been growing bacteria in petri dishes, some people have thought it would be cool to make drawings with them,” Morris said.

The idea to use bacteria growth as pigments for art can be traced to Alexander Fleming, the Scottish biologist who discovered penicillin. In addition to being a scientist, Fleming was a self-taught artist who used bacteria to create drawings and other art.

“He was an artist and had visual acuity both in and out of microbiology,” Adkins said. “This piqued his observational skills, and that’s what we’re trying to harness in students.”

In 2015, the American Society for Microbiology began the Agar Art competition for petri dish art named for the jelly-like substance used to anchor the pigments. Submissions have included portraits of Marilyn Monroe, elaborate snowflake and mandala patterns and drawings of animals such as flamingos, wolves and owls.

“Maybe it was Fleming being a petri dish artist, or maybe I was influenced by the Agar Art contest,” Adkins said. “It was really Dr. Morris who pushed to say, ‘how can we make this educational,’ and I took it from there and developed the curriculum.”

In a class of its own

Adkins and Morris debuted the first petri dish art biology course this past spring, with around 50 students enrolled in the lecture and around 15 in each lab. The students kept a chronicle of their art on Instagram using the hashtag #PetriDishArtUAB.

One of the first winners of the Agar Art competition was a re-creation of Vincent van Gogh’s famous painting “Starry Night.”

One of the first winners of the Agar Art competition was a re-creation of Vincent van Gogh’s famous painting “Starry Night.”

The course is truly interdisciplinary. Adkins said she continually seeks input from others in the departments of chemistry, art and art history and others in biology.

“We are not just doing this venture without artistic consult, but we are consulting with others to ensure best educational practices as we take from other disciplines,” Adkins said.

Both Adkins and Morris have met other microbiology professors and teachers who are implementing petri dish art in their classrooms at other universities, but they said most are smaller projects, and that UAB is likely the only university implementing petri dish art as a larger research project.

|

“This is probably the only course built around art in this kind of way. The whole point is to view it as this platform for stimulating new research.” |

“This is probably the only course built around art in this kind of way,” Morris said. “The whole point is to view it as this platform for stimulating new research.”

The petri dish art lab is a departure from typical undergraduate biology labs, the duo said, where students might do multiple experiments to learn different aspects of biology but never follow through on any particular one. In a lab with Adkins or Morris, students are given the opportunity to see a project through to completion.

“There are countless possibilities,” Adkins said of how a student’s petri dish art might turn out. “It generates the hypotheses itself.”

“Nobody knows what the answer is — your TA doesn’t know, you don’t know, I don’t know,” Morris continued. “We have to figure it out. We think that mirrors research science. We all want students in teaching labs to have open-ended experimentation like a real scientist would.”

A lasting impact

A lasting impact

The research done by students making petri dish art is directly relatable to the areas of research Adkins and Morris are pursuing. Adkins is studying the reasons bacteria create certain pigmentations, and Morris focuses on interspecies interactions in microbes. Pigments can facilitate both antagonistic and cooperative interactions between bacterial species to create things such as antioxidants, chemical weapons or antibiotics, Morris said.

“Some of the research students have done on the petri dish art could be intertwined as publishable data into what I’m doing as a graduate student,” Adkins said. “It’s not like it stops at the end of class.”

Morris added that particularly interesting discoveries made by one section of students could be continued by other iterations of the class.

“At least one or two things we thought were good preliminary nuggets of a real research project could be spun off and explored in more detail by future students,” he said.

Students can register now for the fall class; the prerequisites are BY 123, BY 124 and BY 210.