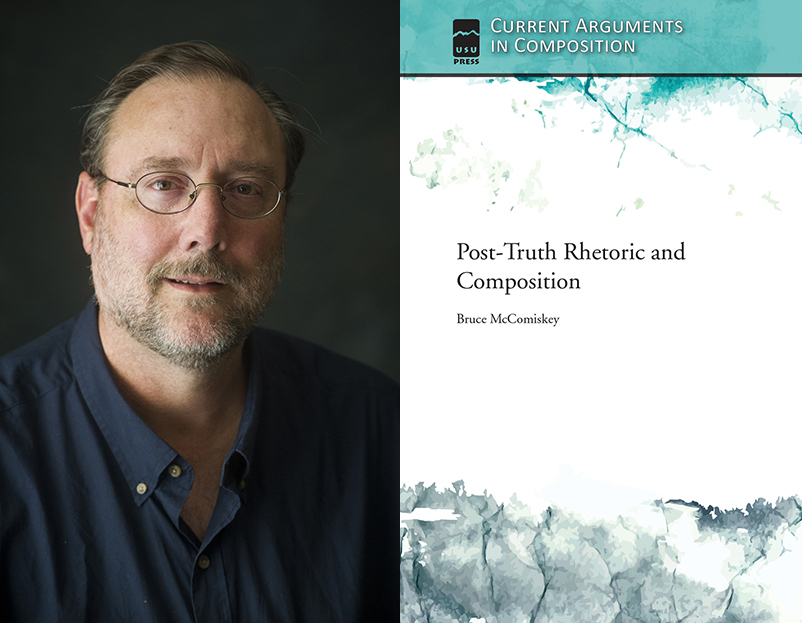

English Professor Bruce McComiskey, Ph.D., and his new book, “Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition,” from Utah State University PressThe basis of rhetorical discourse lies in three means of persuasion, according to Aristotle’s foundational Greek treatise, “Rhetoric.” Ethos is a conviction about the character of the persuader, and pathos is an appeal to the emotions of the audience. The third, logos, is grounded in patterns of reasoning — and it is the loss of logos in modern discourse that inspired English Professor Bruce McComiskey, Ph.D., to write his new book, “Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition,” from Utah State University Press.

English Professor Bruce McComiskey, Ph.D., and his new book, “Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition,” from Utah State University PressThe basis of rhetorical discourse lies in three means of persuasion, according to Aristotle’s foundational Greek treatise, “Rhetoric.” Ethos is a conviction about the character of the persuader, and pathos is an appeal to the emotions of the audience. The third, logos, is grounded in patterns of reasoning — and it is the loss of logos in modern discourse that inspired English Professor Bruce McComiskey, Ph.D., to write his new book, “Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition,” from Utah State University Press.

In “Post-Truth Rhetoric,” McComiskey argues that because logos is the realm of fact, logic, truth and valid reasoning, Western society risks violence, unchecked libel and corrupted elections when forsaking logos in decision-making and critical thinking and relying instead only on ethos and pathos.

Turning points

For McComiskey, this shift in modern discourse was most evident first through Brexit, when Britain voted to leave the European Union, and then in the United States throughout the presidential campaign and 2016 election of President Donald Trump. In fact, he said he began discussing a book about post-truth rhetoric with his editor the day after the U.S. election.

“Trump and his campaign tapped into certain qualities of public discourse that catapulted him [into the presidency],” McComiskey said. “That’s essentially what the book is about.”

The defining characteristic of a post-truth world, according to McComiskey, is that truth is no longer a concern for people when they speak, especially in politics, and therefore language becomes purely strategical. There are no truths or lies, because a lie requires a sense of truth in order to determine it as false.

“Public discourse, it seems, is determined by this falling out of notions of truth and, therefore, notions of lies,” he said. “So, what’s left when you take away truth and lies is just strategic language.”

|

“Emotion is more important than the content of the message. These are difficult qualities of public discourse for rhetoricians to deal with.” |

The Trump team relied heavily on strategic language during the election campaign, McComiskey said, but reiterates the important distinction between the strategic language of post-truth rhetoric and outright lying, which politicians have been doing since the inception of government.

“Politicians forever have lied, but the notion that language is only strategy and doesn’t participate in truth or lies is a fairly recent turn,” he said. “You say things that you think are going to have an effect. It’s not that you are intentionally lying, because that requires a sense of truth. Instead, you’re saying what you think will work to get the desired result.”

Understanding the dilemma

One aspect of post-truth political discourse is the rhetorical strategy of BS, where a persuader is more concerned with the response of the audience than in the accuracy of their statement.

“In BS, the ethos or the character of the speaker is more important than what the speaker actually says,” McComiskey said. “Emotion is more important than the content of the message. These are difficult qualities of public discourse for rhetoricians to deal with.”

One example McComiskey cites is the Trump administration’s January 2017 claim that more than 3 million people voted illegally as reasoning for why he lost the popular vote to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. Because there has been no official count, there isn’t a fact-based account to prove the claim’s truth or falsity.

“All that’s left to say in rebuttal is, ‘I don’t think that’s true,’” McComiskey said. “But no one’s done a count so no one truly knows, so Trump can say ‘3 million people have voted illegally’ and there’s no particular evidence that says it’s not true. The statement’s truth value is irrelevant; it’s a strategic thing to say.”

|

“Politicians forever have lied, but the notion that language is only strategy and doesn’t participate in truth or lies is a fairly recent turn.” |

On the front lines of the battle against post-truth rhetoric are websites such as Politifact and FactCheck.org. The websites believe in objective truth, so they are outside the post-truth realm. The problem with websites such as Politifact, however, is that their work may not convince people who are already under the influence of post-truth strategic language.

“Many people may not believe Politifact because Trump has taken many, if not all, the means of verifying things and called them into question,” McComiskey said, referencing Trump’s reference to the media, specifically CNN, as “fake news.” “He’s trying to discredit people who try to discredit him. A news source like CNN does believe in truth and falsehood — although they have their own political slants as well — but Trump has called fact-checking institutions into question.”

Intentional decision-making

The best way for individuals to combat post-truth rhetoric, McComiskey said, is to and acknowledge the existence of strategic language and not solely rely on ethos and pathos in decision-making.

“There are people like me who care about evidence,” he said. “But the issue is that many don’t care about the truth anymore, which shifts us toward post-truth. Audiences must care about objective truth and evidence and factor that in when forming their opinions and beliefs.”