Discounts? Funny GIFs? Influencers? UAB marketing students must combine creativity and data analysis skills to win with Mimic Social's social media simulation software. Image courtesy Mimic SocialThe purses, pawn shops and crash carts are not real, but the lessons are.

Discounts? Funny GIFs? Influencers? UAB marketing students must combine creativity and data analysis skills to win with Mimic Social's social media simulation software. Image courtesy Mimic SocialThe purses, pawn shops and crash carts are not real, but the lessons are.

Everywhere you look at UAB, computer-based simulations are making an impact on the institution's education, patient care and research missions, combining real-life verisimilitude with video-game-style consequences. If you run into trouble here, you always can try again.

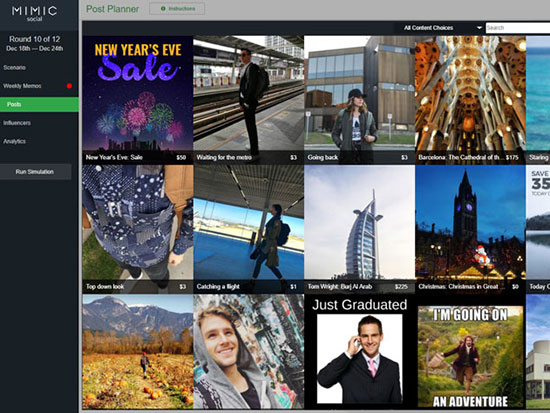

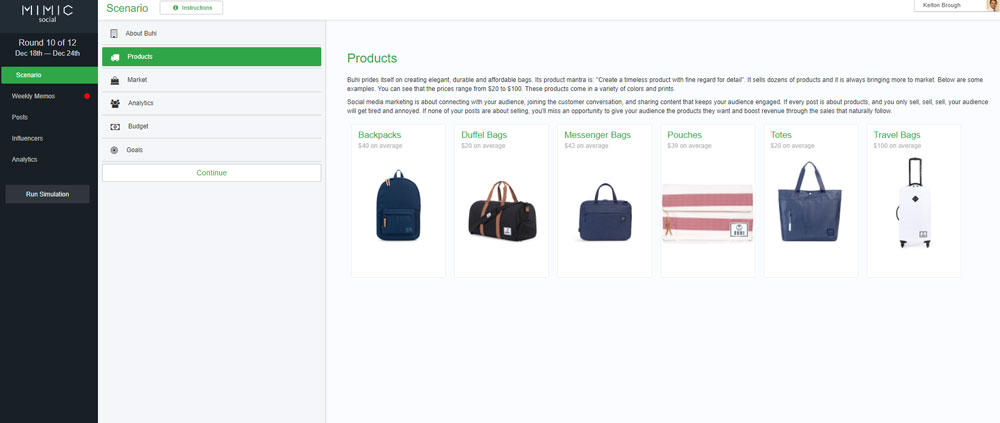

Let's say you have a few thousand dollars and a mandate from your client to generate social buzz around their new Buhi bags. No pressure: It's just your first job on the line. This is the situation facing students in the Collat School of Business's Social Media in Marketing course, which uses Mimic Social simulation software to give students a safe look at the real-life demands they would face in a social-media marketing position.

"It is a very good representation of what being a social-media manager is like," said Lori Sullivan, vice president of marketing at Birmingham-based Fleetio, who teaches the 400-level Social Media in Marketing course. "You are not just creating content, but taking a total ad budget and splitting that between different channels and posts. That takes a lot of critical-thinking skills. When students go out into the real world, a lot of times spending an ad budget is not something they are comfortable with, unless they have had an internship."

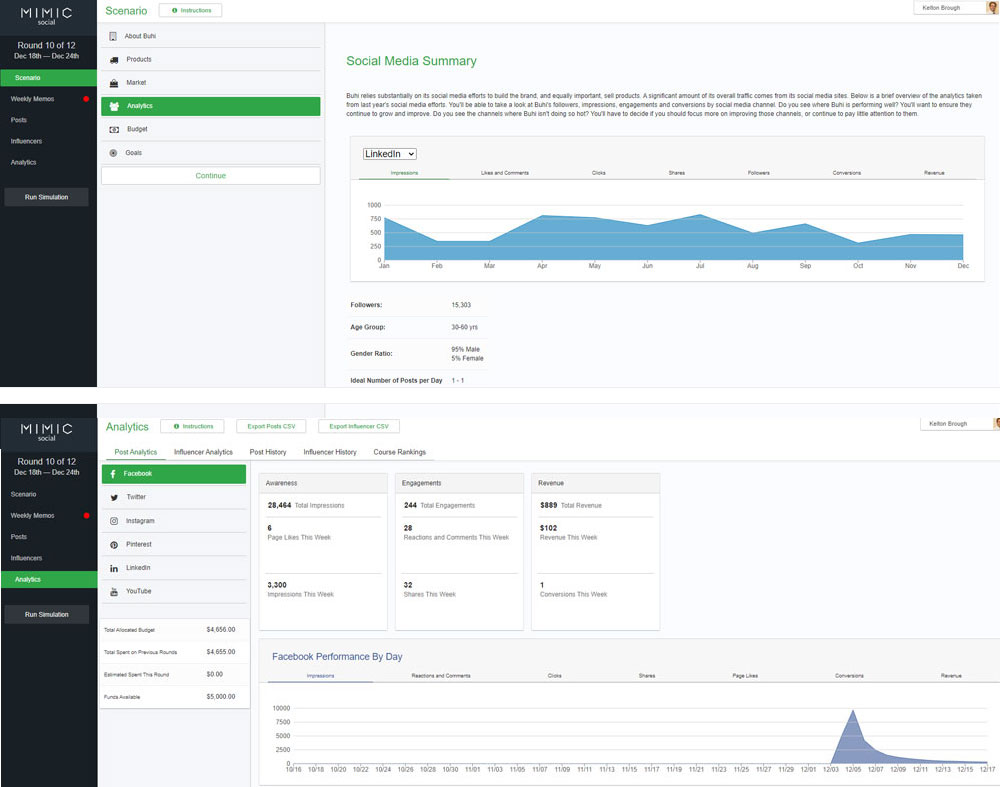

Throughout the semester, students advance through a simulated campaign selling fashion accessories. They develop posts that must be tailored to different social media channels. Then they react to the simulated data generated by Mimic Social in response to those posts by investing their ad budgets in the most promising candidates.

Run the numbers: "You are not just creating content, but taking a total ad budget and splitting that between different channels and posts," said Lori Sullivan, who uses Mimic Social in her Social Media in Marketing course at the Collat School of Business. "That takes a lot of critical-thinking skills." Analysis is a major part of her job as vice president of marketing at Birmingham-based Fleetio. "As data has become more and more tangible, my team's life revolves around metrics and proving performance," she said. Images courtesy Mimic Social.

Run the numbers: "You are not just creating content, but taking a total ad budget and splitting that between different channels and posts," said Lori Sullivan, who uses Mimic Social in her Social Media in Marketing course at the Collat School of Business. "That takes a lot of critical-thinking skills." Analysis is a major part of her job as vice president of marketing at Birmingham-based Fleetio. "As data has become more and more tangible, my team's life revolves around metrics and proving performance," she said. Images courtesy Mimic Social.

Just like in the real world, students have competition. Here, their performances are ranked on a class-wide leaderboard. "It's almost fun," Sullivan said. "You are up against the other people in your class and you really want to perform for your client. For most students, especially if they are interested in social media, this is engaging in a way that a paper or quiz can't be."

The focus on analysis can be eye-opening for students, Sullivan adds. Especially during the past decade, "marketing has become more of a science than an art," she said. "I've done a lot of hiring at Fleetio, and one of the things that I always look for in a marketer is analytical skills. When students think about marketing they think creative and fun, but as data has become more and more tangible, my team's life revolves around metrics and proving performance. To be responsible for proving your ROI [return on investment] on an ad spend and having to report on that puts students in a great place to understand, 'This is what I'm going to be asked to do by my company leadership.'"

See one, sim some, harm none

The UAB Clinical Simulation/Office of Interprofessional Simulation for Innovative Clinical Practice (OIPS) is the hub of UAB’s health care sim city. Its motto: See One, Sim Some, Harm None. That applies whether the students are surgeons in training or future health care workers developing empathy for their future patients.

The UAB Clinical Simulation/OIPS facilities include a floor in UAB Hospital's Quarterback Tower, where former patient rooms and medical equipment are equipped with cameras and microphones to capture the action for detailed post-simulation debriefings. But its largest regular space may be Center Court in the Campus Recreation Center, where OIPS staff and faculty/staff volunteers have run the two-hour Community Action Poverty Simulation for hundreds of undergraduate, graduate and professional students each semester for the past five years.

The students are assigned to small groups representing family units that must survive through a simulated month, broken into four weeks of 15 minutes each. The object is "just try to manage finances and daily life as best as you can," said Dawn Taylor Peterson, Ph.D., director of Faculty Development and Training for the OIPS.

"The Poverty Sim has become part of the required activities in the schools of Medicine, Health Professions, Dentistry, Optometry, as well as UAB’s programs in social work, criminal justice and public health," Peterson said. "Once they get into clinicals, it gives them more of an understanding on the challenges that they will face as future health care professionals."

Simulation plays a role in COVID-19 vaccine rolloutUAB Medicine’s Performance Engineering team and the Clinical Simulation program/Office of Interprofessional Simulation for Innovative Clinical Practice played a critical role in evaluating and refining UAB’s high-stakes plan to begin vaccinating employees and patients against COVID-19. Learn more in this article. |

The Poverty Sim went on a brief hiatus following the pandemic shutdown in March. But it returned in the summer of 2020 as a hybrid experience. After 30 minutes of pre-reading articles on the experience of poverty, students engage with Spent, an online virtual simulation developed by Urban Ministries of Durham in North Carolina. That 30-minute experience is followed by a 45-minute live debrief on Zoom, facilitated by extensively trained volunteers from UAB's faculty and staff who had helped with the in-person Poverty Sim. "It took all summer to get it up and running, but we ran it for the first time in early August with students from Medicine and Dentistry, and it was very successful," Peterson said.

In fact, "I was shocked by the response," she said. "I expected the debriefers to say that these students weren't as engaged as they were used to in person. But what I heard was quite the opposite. They said, 'I love this; my students were so engaged. They were talking.'" The OIPS collects evaluations from every student and "we had amazing comments," Peterson said. "We even had a couple of students who had done it in person and ended up doing it again, just because that is the way their classes worked out. And they said, 'I like this virtual experience better.' To them it seemed much more realistic. In person, the simulation uses paper money and other paper props. But for these 18- and 20-year-olds, who are used to everything being on their phone, that could seem weird," Peterson said. "The virtual platform didn't seem strange to them at all."

Virtual crash carts

The Clinical Simulation team is working on another new simulation method: a training app designed for smartphones that familiarizes them with the emergency carts used in UAB Hospital commonly called a crash cart. Crash carts are rolling, six-drawered units that contain the drugs, supplies and other equipment needed to resuscitate patients who are not breathing or are in cardiac arrest, says Teldra McCord, a clinical simulation specialist for Clinical Simulation/OIPS. They are kept locked, both because the medications inside are potentially dangerous if used incorrectly and because they need to be kept sterile and ready to go in an emergency. "Each crash cart is a one-time use," McCord said. "You pop the lock and use it and then it goes right to be re-stocked."

"Every institution has its own type of crash cart," Peterson said. "Vendors are different, the way the locks pop off are different, the placement of supplies is different." For that reason, Clinical Simulation/OIPS has conducted in-person training for hundreds of caregivers each year during UAB Hospital onboarding sessions. "We have a pre-explore where they get a chance to look through the drawers, then we give them a scavenger hunt and they have to find items during a timed search," McCord said. But these sessions, because they require extensive cleaning and refurbishing of the carts afterward, are expensive to run. Also, “during the in-person orientations, there are only so many people you can get hunting through the cart at the same time," said Brian Mezzell, communications specialist for Clinical Simulation/OIPS. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this in-person training is even more difficult to schedule safely, he said.

For these reasons, "we are now working with Jump Simulation, which is developing a UAB-specific virtual crash cart," McCord said (image shown above). "It will be iOS- and Android-friendly. Clinicians can open the app, and they will see a UAB-specific crash cart. Just like they do in person, they will be able to do a free explore to review what is in the cart and then a timed search where they will be challenged to find equipment in specific drawers."

"Once this is on their phones, it won't go away," Peterson said. "It's a resource. If you are a caregiver and you got called into a code last night and want a refresher, you can pull out the app and go over everything that is in there and where it is located."

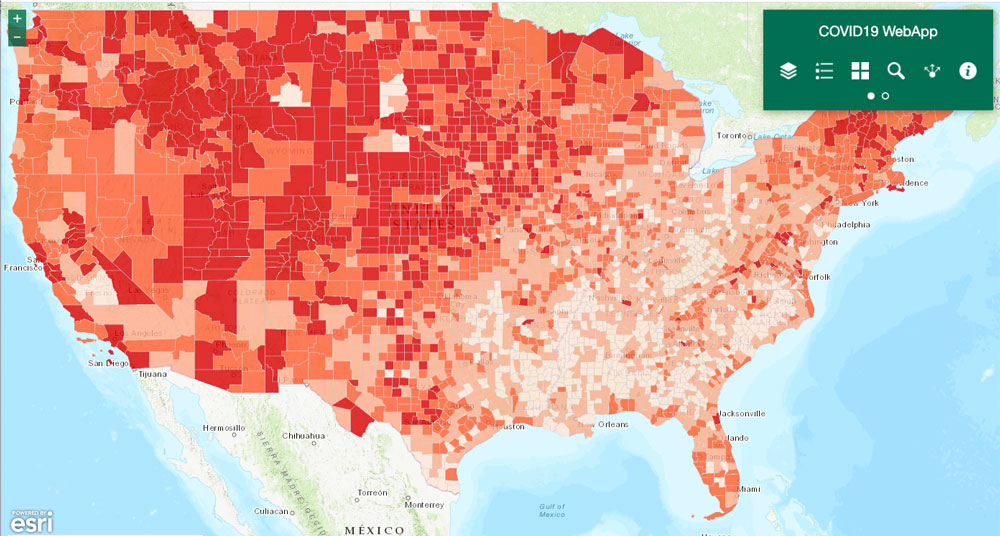

With a pilot grant from the School of Public Health's Back of the Envelope awards program, Assistant Professor Rouzbeh Nazari, Ph.D., and colleagues developed an interactive map modeling COVID-19 risk in every U.S. county based on 11 different factors. See the map online.

With a pilot grant from the School of Public Health's Back of the Envelope awards program, Assistant Professor Rouzbeh Nazari, Ph.D., and colleagues developed an interactive map modeling COVID-19 risk in every U.S. county based on 11 different factors. See the map online.

Modeling storms and county-level COVID data

Computer simulations also are playing a growing role in UAB research projects. When he was on faculty at Rowan University in New Jersey, Rouzbeh Nazari, Ph.D., developed a highly detailed hydrological model of the New Jersey coast. Inspired by the devastation that wrecked the coast during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, he built software that could simulate the impact of severe storms down to individual blocks of houses and could be used to model the snarled traffic as homeowners and visitors rushed to flee the coast in front of a coming hurricane.

Nazari, co-director of the UAB Sustainable Smart Cities Research Center and an associate professor in the School of Engineering Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering and in the School of Public Health Department of Environmental Health Sciences, introduces students to the power of computer modeling in his Water Resources Engineering course. He continues to refine his flooding model and adapt it to the Gulf Coast; with a grant from the National Science Foundation’s I-Corps program, he also is working to turn his simulator into a business.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. With a pilot grant from the School of Public Health’s Back of the Envelope program, Nazari and colleagues used machine-learning to determine which of dozens of population characteristics — age, gender, level of chronic conditions, social distancing success and many other potential factors — were most highly correlated with a county’s COVID-19 infection rate.

They settled on 11 factors that showed the strongest associations. Then the team used modeling and geospatial mapping skills to develop an interactive map showing the vulnerability level of every county nationwide, based on those factors. Other risk-prediction maps online, including one from the New York Times, use reported COVID-19 cases and test-positivity rates alone. “Ours is based on 11 different factors, and applies the fundamentals of the analytical hierarchy process and fuzzy logic to determine vulnerability,” Nazari said.

The project could give public health officials and other decision-makers a new tool to assist in prioritizing targeted interventions. A paper on the research, “Geospatial Assessment of COVID-19 Vulnerability Using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process and Multi Criteria Decision Making Approach at County Level for United States,” now is in press at the journal Applied Geography, Nazari said. “And we are applying for external grants to continue this work.”