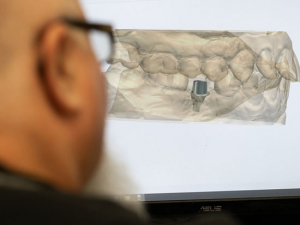

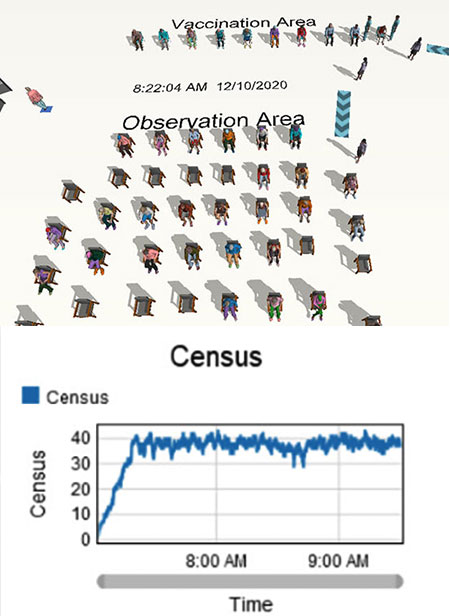

Screenshot from a Performance Engineering simulation of the COVID-19 vaccination site at Margaret Cameron Spain Auditorium on the UAB campus (top) and data output from the simulation showing number of patients at the site over time (bottom).Before UAB’s first group of staff and faculty received their COVID-19 vaccinations in Margaret Cameron Spain Auditorium Dec. 17, 2020, Deborah Flint, senior director for Performance Engineering in UAB Medicine, had seen the day unfold dozens of times.

Screenshot from a Performance Engineering simulation of the COVID-19 vaccination site at Margaret Cameron Spain Auditorium on the UAB campus (top) and data output from the simulation showing number of patients at the site over time (bottom).Before UAB’s first group of staff and faculty received their COVID-19 vaccinations in Margaret Cameron Spain Auditorium Dec. 17, 2020, Deborah Flint, senior director for Performance Engineering in UAB Medicine, had seen the day unfold dozens of times.

Not the actual injections, that is, but the exact sequence of steps that would take the first wave of employees

- into the auditorium’s lobby facing 7th Avenue South

- over to the check-in table

- across to one of the 10 booths set up for the injections themselves

- down into the main auditorium, where they would find an empty seat and wait for 15 minutes to be monitored for any side effects, before

- exiting the doors at the back of the auditorium.

Again and again, during a three-day sprint prior to the start of vaccinations, Flint and her team watched as computer-generated agents arrived on the schedule set for their flesh-and-blood counterparts: 10 at a time, every five minutes. Their job wasn’t to figure out how to distribute the vaccines, but to identify any bottlenecks or inefficiencies in the process. It’s a job that Performance Engineering has done for clinics across the Health System, from the Whitaker Clinic transition to the opening of UAB Medicine’s primary and specialty clinics in Gardendale.

Performance Engineering specializes in space-planning, workflow and patient-flow analyses for ambulatory services in the Kirklin Clinic and other UAB medical facilities, Flint says. The group also is known for its highly visual computational models, which enable them to pre-test new ideas in clinic design and scheduling with no construction dust or patient and staff disruption.

From virtual to physical

After Performance Engineering has analyzed and optimized spaces and processes, they often work with the staff in the Office of Interprofessional Simulation for Innovative Clinical Practice (OIPS), who translate the flowcharts and blueprints into the real world for additional testing. “We do the work behind the scenes with computational models to predict what will happen,” said Lynn Tamblyn, computer simulation specialist for Performance Engineering. “Then we work with Dr. Marjorie Lee [White, director of OIPS] and her team to role-play it out and see if this will really work?”

For the COVID-19 vaccine project, a team led by Sarah Nafziger, M.D., medical director for Employee Health, had planned the workflow process and staffing and chosen the Spain Auditorium location. “They gave us the data on how long they were estimating it would take each staff member to move through the process, from the time they came in the door until they exited,” Flint said. “We knew we would have 10 stations for vaccination, and we knew how large the observation area was and how many chairs were available.” But, she says, we needed answers to the questions: Can we fit in this location? Do we have enough chairs?

A simulated 40 minutes of traffic flow at the Hoover Met vaccination site.

A simulated 40 minutes of traffic flow at the Hoover Met vaccination site.

Performance Engineering’s modeling demonstrated that there were enough chairs, identifying the peak times throughout the day and confirming that the number never got above 47. But it also identified other tweaks to the intended workflow. “Early on we realized that we needed an extra check-in station,” Flint said. “On our simulation, a line started forming — it was a bottleneck. But when we added a third station, that went away.” They also identified a better way to direct patients into and out of Spain Auditorium to increase social distancing throughout. After Flint’s group ran a simulated month of vaccination days, the OIPS team blocked out the stations and roles inside Spain Auditorium itself for several run-throughs.

Additional improvements identified in the in-person work from OIPS have contributed to the current process, which has been lauded for its efficiency, said Dawn Taylor Peterson, Ph.D., director of Faculty Development and Training for OIPS. “I got my vaccine the other day and it was all so smooth,” Peterson said. “It was obvious that so much work went into the flow and timing and every aspect of the process.”

A pilot without the pilot

“We really can pilot without having to pilot,” Flint said. “We can run through multiple scenarios: What if we did checkout in the exam rooms? How many exam rooms do we need? What if we added staff or changed the timing of appointments?” Simulation also can track the results on patient length of stay, wait time, travel time and more. “Then we can look at various proposed future states and see whether they bring improvements or create unexpected bottlenecks and other problems,” she said. “That is the beauty of simulation; your ideas on workflow can change as you run it. We want to know the workflow works before a group physically occupies their new space. If we can look at it while the plans are still on paper, before they finish walls and install equipment we can make sure everything is organized and efficient.”

| Improving patient access and satisfaction is a key component of Forging the Future, UAB’s strategic plan. |

“When a group of doctors and nurses and managers gathers to look at blueprints, they all have different views of what is going on based on paper, but no one can see anyone else’s view,” said Tee Hiett, Ph.D., a retired faculty member in the School of Health Professions and simulation expert who now works with Performance Engineering on a contract basis. “Simulation allows us to turn that 2D blueprint into a miniature movie, so everyone can have a common picture of how a new space, or process, will work.”

FlexSim modeling software — widely used by fast-food franchises, manufacturing plants and the hospitality industry to improve processes — enables Performance Engineering to re-create a clinic’s physical layout, staffing and workflow. They then use actual data from UAB’s electronic systems and their own observations to match real-world conditions. That includes the length of time it takes staff to do different procedures and the fact that a certain percentage of patients will not arrive at their appointments on time, for instance. The end result is a virtual space that can be populated with individual patients and staff, who can each be programmed with different characteristics. With the model built, the simulation runs multiple iterations across several simulated weeks to aggregate performance data.

“We have to know a lot of information about a clinic to have an accurate model,” Tamblyn said. This information — arrival patterns, average duration of various types of appointments — is available through scheduling software and other electronic records. But often, Performance Engineering staff spend time in the clinics, observing and using custom-built iPad apps to track times and calculate distributions and flowcharts of clinic processes. “As we are learning that information, we can find areas the clinic teams may not have explored before” for improvements, Tamblyn said. “Clinic staff may say, ‘Our patients are always late.’ But it may be that they are hitting the front desk 10 minutes before their appointment time, and there is another bottleneck that is throwing the schedule off.”

Simulations let students, staff practice high-stakes skills, from social marketing to surgeryComputer-based simulations offer realism, promote empathy and enable experimentation to practice essential skills. Learn more in this article. |

For a recent project, a client clinic wanted to know the optimum staffing level for the new space it was planning to open. “We were able to show that with two to three staff, their patients would have an 80-minute wait,” Flint said. “With four they would reduce that to 30 minutes and with five they would get to 20 minutes, but then they didn’t gain much more time by adding any more staff. So maybe five staff members was the best option.”

With simulation, Performance Engineering has more to show its clients than charts and tables (although it has those, too). “We can play them the simulation, and they can see with their own eyes how the staffing of a check-in station or level-loading the providers’ schedules has a major impact on their clinic,” Flint said. “Watching it in real time helps our clients understand the power of these changes, and it helps cue us in to opportunities to improve the process as well.”