Adam Gerstenecker, Ph.D., has 42 publications published or in press as well as seven book chapters, primarily looking at changes in functional cognitive ability in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and atypical Parkinsonism.Remember the name Adam Gerstenecker, Ph.D. If you have trouble with that, you may need to give him a call.

Adam Gerstenecker, Ph.D., has 42 publications published or in press as well as seven book chapters, primarily looking at changes in functional cognitive ability in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and atypical Parkinsonism.Remember the name Adam Gerstenecker, Ph.D. If you have trouble with that, you may need to give him a call.

The National Academy of Neuropsychology presented Gerstenecker, an assistant professor in the Department of Neurology, with its early career award at the 3,500-member group’s 2019 annual meeting in San Diego in November 2019. The award is given to those who have made “substantial scholarly contributions to the field of neuropsychology within 10 years of receiving their doctoral degree.” Gerstenecker made it in half that time; he earned his doctorate from the University of Louisville in 2014, and then joined UAB as a fellow. In early 2020, the Federation of Associations in Behavioral and Brain Sciences, of which the National Academy of Neuropsychology is a member, also presented an early career award to Gerstenecker.

Studying neuropsychological measures online

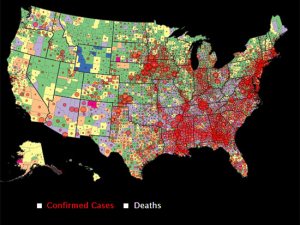

Gerstenecker already has 42 publications published or in press and has authored seven book chapters, primarily looking at changes in functional cognitive ability in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and atypical Parkinsonism. He is principal investigator for an NIH K23 award studying hippocampal atrophy, systemic inflammation and cognition in multiple sclerosis and is an investigator on the Udall Center of Excellence in Parkinson’s Disease Research awarded to UAB in 2018. He also is an investigator for an R01 award that is “taking neuropsychological measures [including the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale and Financial Capacity Instrument] and putting them online in order to conduct mass screenings for people with cognitive and functional decline for early inclusion in drug trials,” Gerstenecker said. “We’re going to have people come in and be administered the measures both online and in person to see how well the results correlate. If that goes well, we’ll roll this out and people can access the battery from their computers.”

Gerstenecker specializes in the use of neuropsychological tests to assess patients with neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, traumatic brain injury and cardiovascular disease. He sees patients in UAB’s neurology clinics who have either reported cognitive change or been referred by a neurologist or other provider who suspects cognitive changes.

| “Once I started studying neuropsychology, I decided to make it my focus. We all find it rewarding to be able to help patients and their families.” |

“We see if cognitive decline is present, evaluate the pattern of change and then try to find what’s causing the change,” using neuropsychological testing, brain imaging and a review of the patient’s medical records, Gerstenecker said. “A lot of times you can’t see changes on an MRI, but you can see diminished performance on neuropsychological tests.” In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, for instance, patients have difficulties encoding new memories.

“We spend a lot of time with our patients and their families, in evaluation and also in educating them,” Gerstenecker said. Between testing and consultation with patients and families, neuropsychologists such as Gerstenecker will spend a half day on a clinical visit. They give recommendations on compensatory strategies and other ways to mitigate any cognitive decline. They also give families an idea of possible future courses of the disease and dangers to be alert for, including mishandling of medications and finances, and an increased risk of depression.

Working toward new therapies

Gerstenecker’s research in patients with brain cancer has highlighted the effect of cognitive changes on the ability to make treatment decisions. This is an important consideration for conditions in which patients can be called on to make life-altering decisions: opting for whole-brain radiation therapy versus focal radiation, for example, or whether or not to participate in a clinical trial.

His research also gives Gerstenecker a way to work toward new therapies for his patients. The multiple sclerosis research funded by his K23 grant is focused first on “seeing if we can find a link between hippocampal atrophy, systemic inflammation and cognitive and functional change,” he said. “Then we can try to reduce the inflammatory load through things like diet, exercise and medical treatment,” with the ultimate goal of improving cognition.

Gerstenecker, who has a brother with a neurological disorder, “was always interested in the brain and particularly why changes in the brain cause changes in cognition,” he said. “Once I started studying neuropsychology, I decided to make it my focus. We all find it rewarding to be able to help patients and their families.”