WHEN REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., WROTE his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in 1963, he was actually behind bars in Titusville, just west of UAB’s campus. This was one of the first neighborhoods in Birmingham where Black people could own commercial and residential property. But times changed. The local industrial jobs moved elsewhere, and today, many of the remaining residents are elderly. The closest store with a variety of fruits and vegetables is a lengthy drive away.

“In Titusville, we always felt like the little ugly child across the street that no one wants to say hello to,” says Bishop Demetrics Roscoe, who, with his wife, Pastor Pauline Roscoe, leads Living Church Ministries in the neighborhood.

Many of the houses don’t have adequate heat in winter or cooling in summer, so the Roscoes open the church building on cold nights and sweltering days. They have distributed food and held GED programs and clothing drives. During the school year, Pastor Roscoe teaches a Bible study for middle-school students at Titusville’s Washington K-8 school, and Bishop Roscoe runs a club for students interested in aviation. (The Roscoe children are all serving in the military and one son was a member of the U.S. Navy’s Blue Angels’ flight team.)

In 2019, a group from UAB led by Mona Fouad, M.D., M.P.H., met with the Roscoes and other community leaders at the church to talk about Live HealthSmart Alabama. The initiative aimed to improve the health of residents in neighborhoods like Titusville, Fouad explained. But she and her team were not bringing a pre-set group of programs or ideas on what was needed.

“I was surprised and encouraged to know that someone else was interested in our community,” Pastor Roscoe says. “They asked about the needs, and I suggested some way to get fresh, healthy foods, because Titusville is a food desert.”

Before long, the Live HealthSmart Alabama team returned with the Mobile Market. It is a grocery store on wheels, packed with fresh, local produce and proteins such as chicken. Created in partnership with two nearby nonprofits, the Mobile Market offers low prices and a wide variety of payment options, including Double Up Bucks, a national program that lets customers spend twice their SNAP or EBT purchases up to $20 if they are buying fruits and vegetables. The Mobile Market comes to Titusville regularly as it makes the rounds of several Birmingham neighborhoods. It always draws a crowd. “The Mobile Market has been such a blessing to people in the neighborhood,” Pastor Roscoe says.

“Once people realize where we are, they are repeat customers every time,” says Angela Arrington, of PEER Inc., who handles operations for the Mobile Market. “They come out in the rain, shine, cold, and hot.” PEER runs several food-related programs in East Lake, including a farmer’s market, diner, and bakery. Arrington had started a monthly mobile farm stand out of the East Lake Farmer’s Market, taking boxes of produce, a tent, and a table in a van or her SUV. Live HealthSmart Alabama expanded on the idea and purchased the truck and trailer needed to make it happen. Arrington’s connections to local farmers through the farmer’s market, plus purchasing in conjunction with an East Lake grocer, supplies the Mobile Market with produce as well as meats, dairy, flour, and more. Especially during the warmer months, fruits and vegetables don’t stay on the shelves long. “All summer long, everyone was buying all the produce,” Arrington says. The Double Up Bucks especially help shoppers fill their pantries, she adds. “They can spend $20 on groceries and get $20 of fresh produce. So you don’t have to say, ‘I would love to get produce, but I can’t afford it.’”

A Grand Challenge

Live HealthSmart Alabama was the inaugural winner of UAB’s Grand Challenge in 2019 and had just begun to roll out as the pandemic began. “We had to pivot when COVID hit, but we didn’t stop and stay behind our walls at UAB,” says Fouad, who is chief executive officer of Live HealthSmart Alabama, professor in the Heersink School of Medicine, and director of the UAB Minority Health & Health Disparities Research Center. The relationships and experience built over 20 years with the MHRC “was the foundation for Live HealthSmart Alabama,” Fouad says. “What we learned made us ready to roll out something really ambitious.”

Chief among those lessons is the importance of asking communities what they need and proving that you are there for the long term. Titusville and East Lake, plus two other neighborhoods—Kingston and Bush Hills—were selected as the first Live HealthSmart Alabama demonstration zones. All were short on COVID testing and sources of information about the disease that people could trust.

But they already trusted the Roscoes. “People in the community know us and see us partnering with UAB,” Pastor Roscoe says. “That helps them know they can trust UAB.”

By working with the UAB Health System and the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham, Live HealthSmart Alabama brought mobile COVID testing to churches such as Living Church Ministries and other community gathering places. In Oct. 2021, Live HealthSmart Alabama launched a counterpart to the Mobile Market. The Mobile Wellness Van is staffed by UAB medical students and offers free blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, and other screenings, as well as education on topics such as how to quit smoking.

In partnership with Live HealthSmart Alabama, young men with the Determined to Be program, founded by Milton King, tend the community garden in Kingston.

In partnership with Live HealthSmart Alabama, young men with the Determined to Be program, founded by Milton King, tend the community garden in Kingston.

The pandemic paused many of the planned educational events and health fairs in its demonstration zones, but Fouad and her team decided to press ahead with another pillar of their plan: improving the built environment in those zones to encourage physical activity, wellness, and good nutrition.

“Construction companies and the city—our key partners—continued to work even while everything else was shut down,” Fouad says. In 2020 and 2021, Titusville residents gained 7,900 linear feet of new sidewalks, brighter street lighting, two new heated bus shelters, and more trees on First Street South, the neighborhood’s main north-south street. Titusville also got Birmingham’s first Neighborway—a mile-long, specially designed street that can accommodate biking, walking, and skating, as well as driving. The Neighborway runs from Loveman Village at Titusville’s western edge to the renovated Memorial Park on its eastern border.

“People saw that we were improving where they live, investing in their communities,” Fouad says. “You don’t know that your neighbor’s blood pressure has improved, but you can see that the sidewalks are fixed, and the parks are improved, and that builds trust. Now that they trust us, when the Mobile Wellness van comes, they are more likely to come out.”

“UAB didn’t say we want to do something with you and disappear,” Bishop Roscoe says. “They are still coming, talking to us and working with us. It reminds me as pastor, we have to look for hope.”

Bishop Demetrics Roscoe and his wife Pastor Pauline Roscoe of Titusville.

Bishop Demetrics Roscoe and his wife Pastor Pauline Roscoe of Titusville.

Nothing changes if nothing changes

A few miles to the northeast in Kingston, Live HealthSmart Alabama has brought more infrastructure improvements, including new sidewalks and trees to protect pedestrians along busy Messer Airport Highway; a major overhaul for the city’s only park, Stockham Park; painted murals; new bus shelters; and improved lighting.

A new sidewalk, which “is big enough for two people to walk side by side,” is changing the mood at Kingston’s Hayes K-8 school, says principal Natasha Flowers. “Teachers can now stand next to the kids when they are walking to and from school so they can watch them and make sure they are safe,” she says. And just to the north, in the neighborhood’s Rev. Dr. Morrell Todd Community, is another new green space: a teaching garden where Milton King and his young mentees grow vegetables and practice life skills.

The teaching garden “is a permanent, positive outlet—and there are very few permanent, positive outlets in underserved communities,” says King, founder and executive director of Determined to Be, a mentoring and leadership program for boys and teens from nine to 19 years old. King started the nonprofit in 2016, using what he calls “exposure trips” to open the eyes of the young men to different worlds and possibilities. They go on outings to Top Golf, football games, and restaurants, and on community service visits to local nursing homes, where they talk with residents “about what they did in their past careers and about their family members,” King says. “That teaches them relationship-building and one of the pillars of character, which is caring.”

In the teaching garden, his young men “learn the skills of gardening and learn to identify what is good for their diet,” King says. “But the garden also allows them to be a part of something, to take pride in their own community. They are involved in their community instead of standing on the sidelines watching the adults do the work. To see the joy that they get from us planting something and seeing it move along to harvest—that has done a lot for their self-esteem.”

“We’re a grassroots program—to have an organization come and support and help us has really been beneficial,” King says. “We want to continue to work side-by-side with Live HealthSmart Alabama to show the young men that healthy people create a healthier community.”

To celebrate the opening of the updated Stockham Park and its vibrant new mural celebrating Kingston, along with new sidewalks, bright lighting and other improvements, Live HealthSmart Alabama organized a community cleanup day. “Residents of the housing community, the neighborhood association, the fire department, UAB students and faculty—everyone came out and literally cleaned up all of Kingston,” says Kimberly Speights, a Kingston native who has led several community-focused nonprofits in Birmingham and is now serving as a community engagement manager for Live HealthSmart Alabama.

“When I was growing up, there was a sense of unity in the neighborhood, but over time that disappeared,” Speights continues. “It meant so much to me to see that unity back. Just to be able to go into the community and provide the services they are asking for—everybody is excited about things and talking, ‘What are we doing next?’ Every part of Kingston is communicating with each other.”

Success breeds success

“The mayor’s number-one priority has been and continues to be neighborhood revitalization,” says James Fowler, director of Transportation for the City of Birmingham. “The entire Live HealthSmart Alabama initiative fits in really well with that. It’s awesome for an outside agency to step in and focus resources on neighborhoods that really need it, and we can learn about real outcomes from that focused investment,” Fowler says. “And the residents are at the heart of it all, which is exactly where they need to be.”

Fowler’s team meets twice weekly with staff from UAB’s Sustainable Smart Cities Research Center, which is led by Fouad Fouad, Ph.D., professor and long-time chair of the Department of Civil Engineering in the School of Engineering (he also is Mona Fouad’s husband). “Keeping pace with UAB’s investment has required a major investment of our own staff resources and time, and the process has absolutely been worthwhile,” Fowler says. “We are seeing the results of that investment and we are extrememly grateful to UAB.”

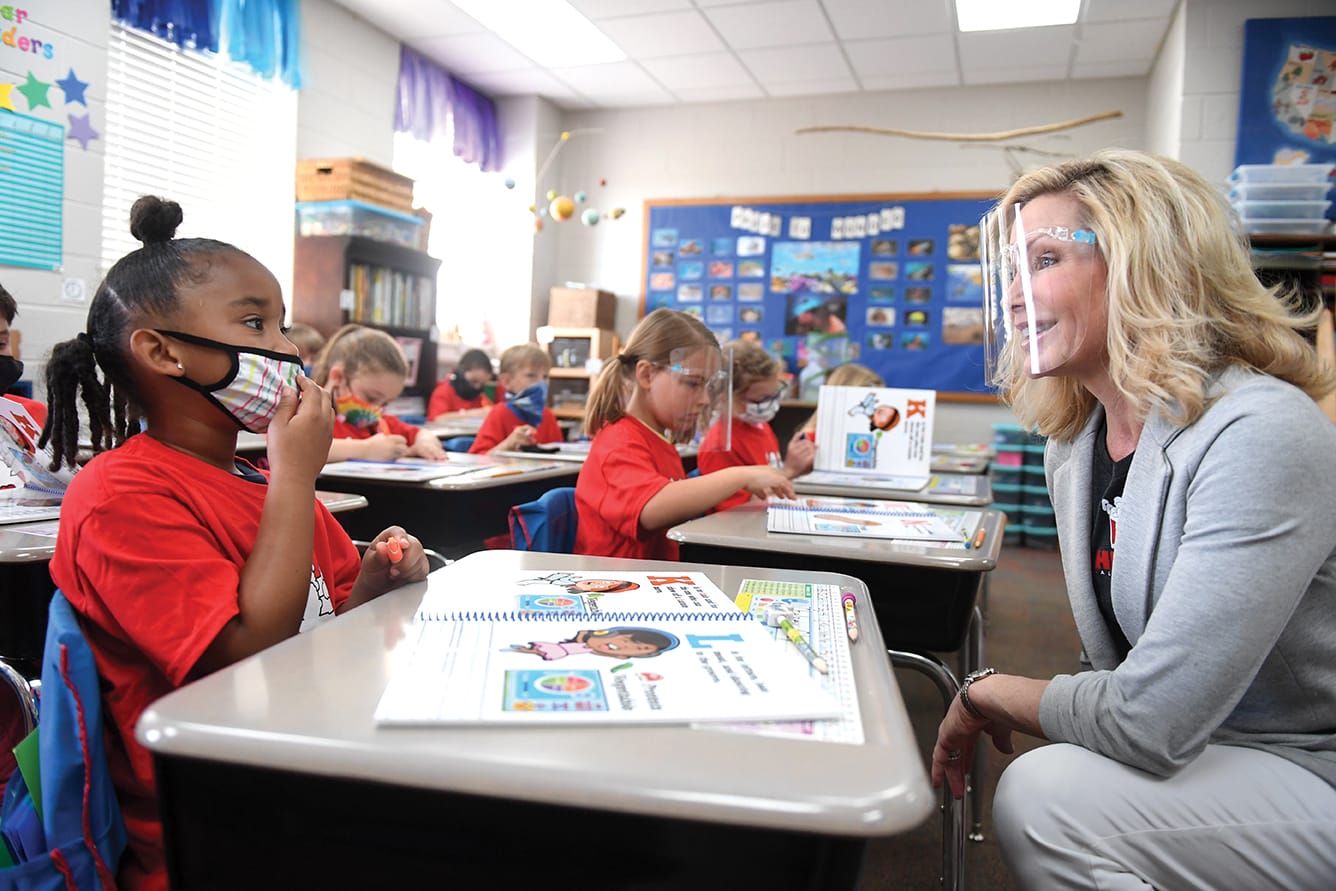

Christy Swaid, founder of HEAL United, with students at Phillips Academy.

Christy Swaid, founder of HEAL United, with students at Phillips Academy.

Live HealthSmart Alabama’s success also depends on the partnership of companies such as Dunn Construction, Vulcan Materials, National Cement, and Goodwin Mills Cawood. “We asked for help with sidewalks and lights,” Mona Fouad said. “They said, ‘We want to do that and the [educational] programming as well.’ A lot of their workforce and families live in these neighborhoods and they never had a way to connect with them until now.”

“Service to our communities is a cornerstone of the Dunn Companies’ values, and we are proud to invest in Live HealthSmart Alabama and support UAB and the City of Birmingham in improving the lives of its citizens through healthier living in the built environment,” says Craig Fleming, president of Dunn Construction and chair of the Advisory Board of the UAB Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering.

“It has been a great and rewarding experience working with the City of Birmingham and Alabama corporations to plan and accomplish the built environment improvements in Kingston, Titusville, Bush Hills and East Lake,” Fouad Fouad says. “I believe these strong partnerships between academia and industry are built to last forever.”

“Now that we have become known, a lot of other organizations have come to us and said, ‘How can we help?’” Mona Fouad says. “It has connected all these people together to get to that same mission.”

One of those organizations was Protective Life Corporation, which named the new football stadium downtown that is home to the UAB Blazers “Protective Life sponsored this beautiful new stadium and they wanted to improve the neighborhoods around the stadium as well,” Fouad says. “They came to us and said, ‘Can you replicate your models here?’ So now we are in five more neighborhoods."

It’s who you know that matters

The changes in Kingston, Titusville, and Bush Hills would not have been possible without a close partnership between Making changes statewide will require spreading the Live HealthSmart Alabama game plan to communities across the state. Live HealthSmart Alabama is now developing a playbook explaining how to do just that. “First we tell them, ‘You have to develop your infrastructure,’” Fouad says. “You need to get an academic institution, a health system, faith-based organizations, and a health department on board.” When Live HealthSmart Alabama kicked off in Birmingham, for example, UAB President Ray Watts, M.D., reached out to Mayor Randall Woodfin to explain the initiative and ask for the city’s support and collaboration. The playbook systematizes such contacts, which help to generate leadership buy-in from the very beginning.

In 2022, Live HealthSmart Alabama will expand to Selma and Dallas County, its first rural area. Plans call for an expansion to more Birmingham neighborhoods and to cities around the state—including Montgomery, Tuscaloosa, Dothan, and Mobile—by 2024. (UAB recently announced it would fund Live HealthSmart Alabama for an additional two years, for a total of $5 million.)

As the Live HealthSmart Alabama initiative grows, it continues to attract new talent. After Teresa Shufflebarger joined as chief administrative officer in Feb. 2021, she embarked on a tour of each UAB school to seek out ways to connect faculty and students with the project. “I was amazed by the depth of resources in schools that they want to share with the community,” Shufflebarger says. “UAB is pulling together to leverage the talents and skills and expertise that lie within the university.” (UAB’s campus is the fifth Live HealthSmart Alabama demonstration zone, and efforts began in earnest in Jan. 2022.)

Mona Fouad, M.D., Edward Partridge, M.D., Dalton Norwood, Ph.D., Angela Arrington, Kimberly Speights, Susan Driggers and the Live HealthSmart Alabama Mobile Market and Mobile Wellness teams, including partners from P.E.E.R. and East Lake Market.

Mona Fouad, M.D., Edward Partridge, M.D., Dalton Norwood, Ph.D., Angela Arrington, Kimberly Speights, Susan Driggers and the Live HealthSmart Alabama Mobile Market and Mobile Wellness teams, including partners from P.E.E.R. and East Lake Market.

Shufflebarger has tapped into students at schools across campus and their “bright, excited brains” for a wide range of projects, she says. Dylan Angeline is part of a group of UAB MBA students working on the effort around Protective Stadium—specifically, how to let the community know what is happening, and why.

For example, “How would you let a family know that the Mobile Market is going to be in the Northside?” Angeline says. Should you use social media, flyers sent to schools, letters, radio? The students did a deep dive into the published research and theory on the topic and created a communications plan incorporating best practices for reaching a variety of demographic types, from teens to retirees. “It is a cheat sheet that you can give to any member of the organization, from CEO to volunteer,” Angeline says.

Kellie Barrett, a graduate student pursuing dual master’s degrees in Health Services Administration and Health Informatics, worked with Shufflebarger to complete the playbook. “It’s a guide to start the Live HealthSmart Alabama movement in communities across the state,” Barrett says. The book outlines 10 steps to help community leaders identify community needs, engage community members in interventions and implement plans into action. “We hope the playbook will empower communities across the state to change policies, change systems, change environments and foster healthier living,” Barrett says.

“No one else nationally is doing something like this,” Fouad says. “There is no comparable model. We are building the Alabama model for the rest of the country to adopt.”