Like many Alabamians, Kelcey McAllister and Erika Cooper grew up spending summer days on the water. For Cooper, it was the Coosa River’s Lay Lake and Lake Mitchell, where the Sylacauga native enjoyed fishing for her dinner. McAllister, who is from Dothan, recalls casting lines for bass and catfish in Lake Eufaula. “We ate fish all the time—every way you could cook a fish,” says McAllister. “We’d store it so that we could eat it all year long.”

So when the two UAB public health majors learned that fish caught in local waters could be bad for their health and threaten their families and friends, the lessons hit close to home. The risk is even greater, they discovered, for people who depend on Alabama’s lakes and rivers to put food on their table each week.

Pollution on Your Plate

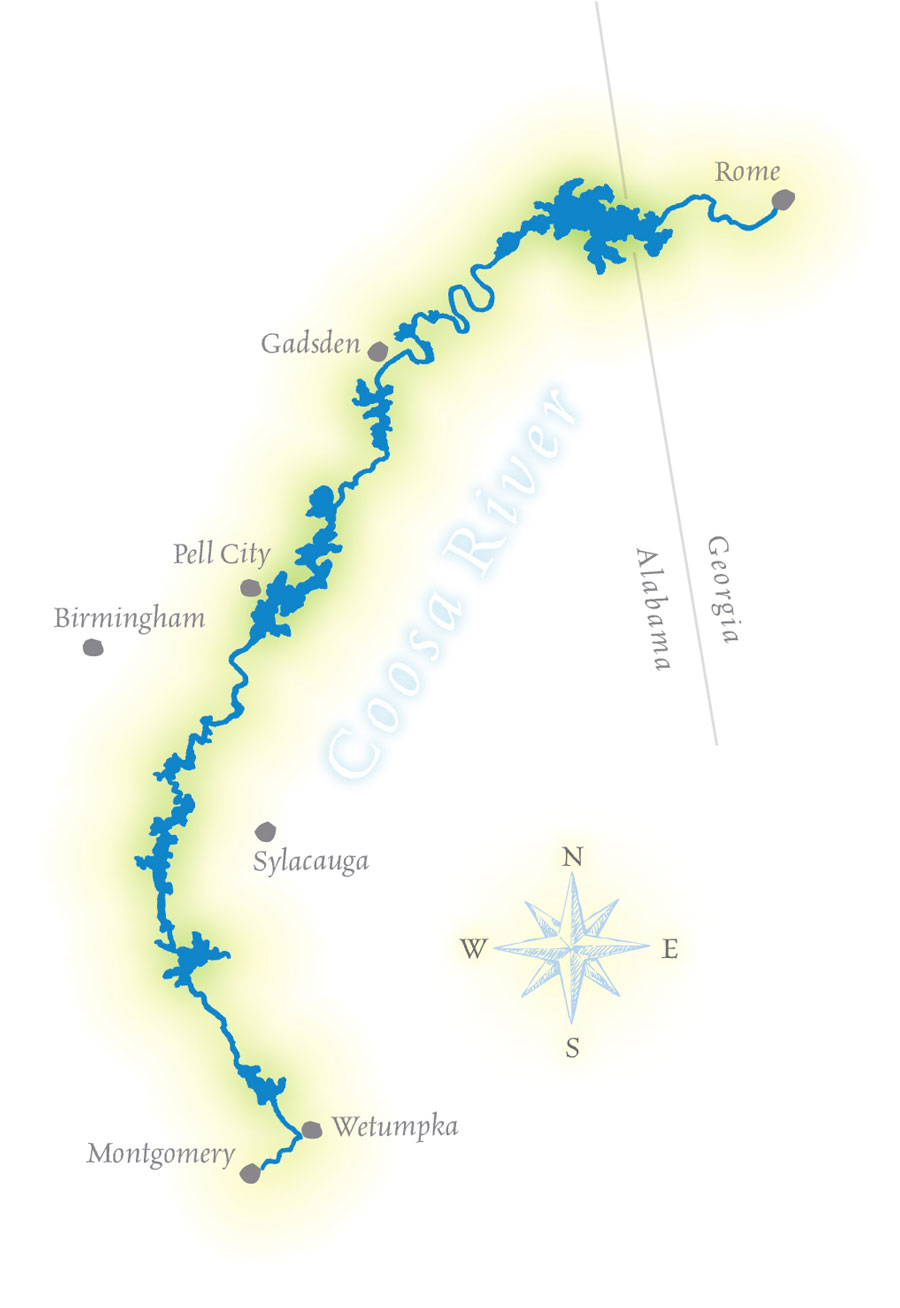

That discovery came in a service-learning experience developed by Dale Dickinson, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental health sciences in the UAB School of Public Health, in partnership with Coosa Riverkeeper. The nonprofit conservation group, which attends to a watershed of 5,000 square miles, is part of an international Waterkeeper Alliance of more than 250 organizations focused on protecting local waterways.

“The Coosa River has high levels of PCBs and methyl-mercury,” says Dickinson. “PCBs are linked to cancer and methyl-mercury to some neurological issues, including ADHD. Both compounds accumulate in fish. We eat the fish and then these compounds accumulate in us.”

Dale Dickinson examines the effects of pollution on health and society.

Dale Dickinson examines the effects of pollution on health and society.That’s usually not a problem if your fish comes from supermarkets, but initial research by UAB public health students and other Riverkeeper volunteers suggests that nearly three out of four people who fish the Coosa take those fish home to their families. More than 65 percent of those interviewed with lines in the polluted waters said they fish frequently—a third of those more than once a week. More than half had not heard of PCBs or methyl-mercury or knew of ways to reduce their families' exposure to them.

This is an example of the community-level impact of environmental contamination, Dickinson says. Two of his courses—Food, Water, and Air and Environmental Justice and Ethics—examine the disproportionate burden on people who live in areas impacted by multiple pollution sources. Historically, these residents have included minorities and people at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder.

“We can talk about environmental contamination and poor neighborhoods in the classroom, and people feel sad,” Dickinson says. “When students get out and see it for the first time, it opens their eyes that they are preparing to be professionals in public health. For example, they can see eight people fishing, and this is their dinner for the next few days—and we know it has dangerous levels of PCBs in it.”

Spreading the Word

In fact, those levels are high enough that the Alabama Department of Public Health has issued some 26 fish advisories on the Coosa River. But many anglers don’t know about them, a fact that surprised Cooper. “If there’s a consumption advisory that the fish are contaminated, then you should not eat them,” she says.

With just two full-time staff members, Coosa Riverkeeper welcomes efforts by students to spread the word, says executive director Justinn Overton. UAB’s service-learning activities go to the heart of the group’s focus on education, she explains. Through interviews and other activities, the students have helped provide quotes from local anglers, pictures, and videos for use in public information campaigns and related publications.

Kelcey McAllister (left) and Erika Cooper (right) helped Coosa Riverkeeper clean the waterway and inform the public about contaminants.

Kelcey McAllister (left) and Erika Cooper (right) helped Coosa Riverkeeper clean the waterway and inform the public about contaminants.“Our goal is to get information about these advisories to the people who need it the most—subsistence fishermen,” says Overton. The fish they catch is often their primary source of protein.

Cooper spent the spring semester at Coosa Riverkeeper developing an online fishing guide. It includes a map showing places where fish are safe to eat, guidance on the frequency of consuming contaminated fish, advisory explanations, and cooking tips. She also researched other states issuing advisories to learn how they gather and disseminate the information.

McAllister, who helped clean up nearly 600 pounds of trash from Lay Lake one Saturday last fall along with Cooper and more than 60 other volunteers, tackled another aspect of the pollution problem. She helped to create a Standard Operating Procedure for river clean-up. Overton calls it a living document, a step-by-step guide that can be implemented with other watershed groups.

The community also benefits from the service-learning partnership, Dickinson says. “They get to talk to the students and begin to find out what is going on in the waterways, and what the issues are,” he says. Food preparation is one critical topic of discussion, he says.

“The compounds get stored in fat,” Dickinson explains. “If you remove the fish skin, then that removes a lot of the PCB load. But if you simply fillet it and deep fry it in oil, then you are eating the skin, so you are getting a lot of the PCBs.” Those also leach into the cooking oil; if you use it again for the rest of your meal, then your French fries and onion rings are also contaminated.

Career Challenges

McAllister and Cooper both graduated in April and plan to return to UAB for master’s degrees in environmental health in toxicology. But their work with Dickinson and Coosa Riverkeeper has already helped prepare them for big challenges they will face as public health practitioners.

“I can sympathize with the fishermen,” Cooper says. “That’s their lifestyle, and that’s what they love to eat. So how do we change behavior? We can’t just come into their homes and communities and change it. Even with as much evidence as we have, it will be a long battle.”

The Coosa River’s 280-mile course includes many stretches of tranquil beauty.

The Coosa River’s 280-mile course includes many stretches of tranquil beauty.