Need more information? Contact us

Click to enlargeResearchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham have taken an in-depth look at patterns in pediatric sports-related injuries in a new study published in the Journal of Athletic Training.

Click to enlargeResearchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham have taken an in-depth look at patterns in pediatric sports-related injuries in a new study published in the Journal of Athletic Training.

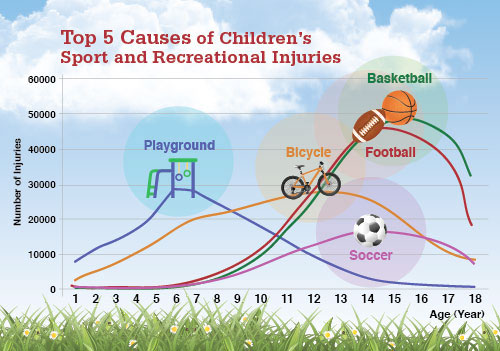

The study suggests that tailoring safety regulations more closely by age could impact the incidence of injury. It examined records of more than 2.5 million children ages 1-18 who were seen in hospital emergency departments for sports or recreation injuries during an eight-year study period. Among those, the five most common causes across all of childhood were basketball, football, bicycling, playgrounds and soccer.

David Schwebel, Ph.D., associate dean for Research in the Sciences and professor in the Department of Psychology, and Carl Brezausek, M.S., former researcher in the Center for Educational Accountability and instructor in the UAB School of Education, analyzed data spanning 2001-08 from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, a database of injuries treated at hospital emergency departments.

“There are huge numbers of children in the United States who play sports,” said Schwebel, who directs the UAB Youth Safety Lab. “Injuries can and do occur when children are active in sports-related activities, and often they could be prevented.”

The study focused on patterns in injury incidents by exact age and gender. Epidemiology studies on injury often divide children into five-year age spans that fail to precisely account for developmental differences, Schwebel says.

| “We see this most clearly in the early years. Children show increasing independence from their parents, and they’re learning what their body can and can’t do. Children have to constantly evaluate their body’s capacity in terms of balancing, reaching, jumping or leaping, or hitting an opponent or a teammate. Part of that evaluation is physical, part of it is judgment, and part is in cognitive and decision-making skills." |

“Five-year spans are the historical breakdown of most epidemiological data,” he said. “With adults, that breakdown makes sense. There’s not a huge difference between a 40-year-old and a 44-year-old in terms of injury risk, but there is a huge difference between a 1-year-old and a 4-year-old or even between a 5-year-old and a 9-year-old.

“We see this most clearly in the early years. Children show increasing independence from their parents, and they’re learning what their body can and can’t do. Children have to constantly evaluate their body’s capacity in terms of balancing, reaching, jumping or leaping, or hitting an opponent or a teammate. Part of that evaluation is physical, part of it is judgment, and part is in cognitive and decision-making skills.”

The data showed injuries related to certain recreation activities peaking around specific ages — playground-related injuries remained relevant up to age 9 — while activities such as bicycling caused injuries throughout the age span. Injuries peaked overall at age 14. Bowling caused the most injuries to children at the youngest age (age 4), and camping and personal watercraft caused the most injuries to the oldest (age 18).

However, Schwebel emphasized that the study should not discourage parents from allowing children to participate in sports and recreation activities.

“There are more positives than negatives,” he said. “We should continue to preach safety in activities that are organized and activities that are unorganized. I think it’s the task of parents, coaches, school administrators and even children themselves to be wary that injuries can and do occur and that most are preventable.”