Gary Chapman began thinking of ways society had changed in the 10 years since the 9/11 attacks and was struck by inspiration.

The artist, a professor of painting at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who creates large, distinctive paintings that often feature realistic portrayals of people, had the idea to create a series of smaller paintings.

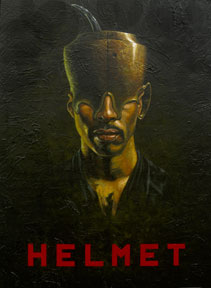

“I kept coming back to this idea of these heads wearing helmets. I knew the helmets would be designed to block eyesight,” he says. “It was like a flashback, I didn’t know what they were about. A month later, I re-visited the idea. I started thinking about all that had happened in the past 10 years, and a statement crystalized in my head. I quickly wrote it down, and it became the vision for the project. It was then clear to me, what the series was about.”

That statement was this: “At 8 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001, it was easy to perceive our lives as serene; we were safe. Even while Bernie Madoff’s crimes were being exposed, most saw our economy, our country, as prosperous; we led the world. And while the scientific community embraces a vision of quantum mechanics and string theory, shattering our basic understanding of the observable universe, we are left behind only capable of viewing Newton’s world; we are blind. We are a visually biased society, living in a time in which we can no longer believe in what we see.”

|

|

| Photo credit: Steve Wood, UAB |

Thus was born The HELMET Project, which has evolved to be more than 12 paintings to hang in a gallery. Chapman began work by using himself as a prototype. Then he photographed people of interest to him; his daughter, a man who worked in the building that houses his studio, friends and students. He worked on all 12 paintings at the same time.

The subjects in Chapman’s paintings are hindered by their headwear, each helmet unique and born from Chapman’s imagination. Each subject is protected, but hindered; sightless and yet empowered. They represent a decade at war with an enemy not clearly identifiable, one we cannot see; an economy tanked with only hindsight revealing the fault lines, Chapman wrote about the project on his website, www.garychapmanart.com. They seem to be asking us, Chapman suggests, “can we no longer trust or believe what we see?”

Chapman envisioned images of the paintings hung in intriguing places throughout the greater Birmingham area, even the state. He drove around the city, viewing abandoned buildings, interstate underpasses, long corridors and old bank vaults — places he thought architecturally interesting and conceptually complementary to the project — to choose his locations.

Although he usually works alone, Chapman wanted to collaborate with other artists to create a collection of photographs of installations that potentially would become a book. When the paintings were completed en masse in July, Chapman began working with Birmingham photographer Liesa Cole, who saw his vision and met it with inspiration of her own. She wrote an essay and shot installations of the paintings for a four-page spread in the September issue of b-Metro magazine.

|

| Photo credit: Collaboration - Bradley Boyd and Jon Cook Photography |

“It was intriguing to accompany Gary on several of his installation missions,” Cole writes in the essay. “Each environment presented a unique set of challenges and yielded an entirely different effect. Underneath the overgrown underpass by Sloss furnaces, I felt like I was spying on military combatants skulking blindfolded through a cloistered jungle in military formation. The abandoned smokehouse chamber was haunting and post-apocalyptic in its gritty underworld way. Then the brightly lit library, flanked by the voluntarily sightless figures suggested a deliberate avoidance of facts and information. The setting of the print shop, with all of those machines designed to multiply and disperse information seemed to decry an intentional ignorance of a different sort, one more imposed than chosen. I found myself thinking about propaganda and how misinformation or distortions are such powerful tools of manipulation.”

Even though the paintings themselves have been a year in the making, in many ways the Helmet project is just beginning. Chapman is working with other Alabama photographers, and now a few writers are on board. Three UAB locations have already been used in the project and more are to follow.

The project continues to evolve, which is both exciting and intimidating for Chapman. As he says, “I have no idea how far this will go, or when and where it will end.”