Examining Physicians’ Roles in Film and Fiction

By Matt Windsor

Not many professors of medicine get to teach a course starring Cary Grant—and Sinclair Lewis. But the Doctor in Film, Fiction, and History is no ordinary class.

Each fall, H. Hughes Evans, M.D., Ph.D., the chair of the Department of Medical Education at the UAB School of Medicine, offers busy students the chance to put down their textbooks in favor of novels and popular films. Evans’s class is one of a growing number of Special Topics courses developed by faculty members at the School of Medicine; the weeklong courses are offered to students four times per year. Entertainment is not the object, however; Evans’s curriculum is designed to help students learn what society—that is, their future patients—expects from them as doctors.

“It’s easy to forget what it is like to be a patient,” says fourth-year student Erinn Schmit. “I thought this would be a good way to learn a little bit about my patients’ perspectives on what a doctor’s role should be.”

|

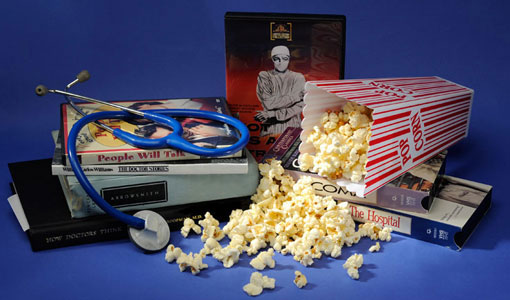

Play List A selection of films and novels that Hughes Evans has featured in the Doctor in Film, Fiction, and History: Films People Will Talk (1951) Not As a Stranger (1955) MASH (1970) The Hospital (1971) Coma (1978) Awakenings (1990) The Doctor (1991) Bramwell (1995) Something the Lord Made (2004) Fiction A Country Doctor (1884) by Sarah Orne Jewett Arrowsmith (1924) by Sinclair Lewis The Citadel (1937) by A.J. Cronin The House of God (1978) by Samuel Shem The Doctor Stories (1984)by William Carlos Williams The Doctors (1988) by Erich Segal Cutting for Stone (2009) by Abraham Verghese |

Admit One

Evans may start out with People Will Talk, a 1951 comedy/drama starring Cary Grant as irreverent gynecologist Noah Praetorius—or 1940’s Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet, in which Edward G. Robinson plays the role of the real-life researcher who found a cure for syphilis. The movies are paired with timeless fiction about the medical profession, including Sinclair Lewis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Arrowsmith; The Doctor Stories by William Carlos Williams; and—the students’ favorite, Evans says—the satirical The House of God by Samuel Shem.

In one class meeting this fall, the discussion shifted quickly between an analysis of the 1978 thriller Coma and the classic 1984 essay “Facing Our Mistakes” by physician David Hilfiker. “The hierarchical system of medicine, especially in the time periods covered by this movie and essay, makes it hard to deal with mistakes,” Evans pointed out to her students. She then asked them to discuss times when they had been placed in the tricky position of reporting a medical error.

“There are lots of great articles and books that explore what it means to be a doctor and the pressures that physicians face,” Evans says. “It can be intimidating to jump into that discussion, but everyone can talk about movies. So we use the readings to help deepen the dialogue that begins with movies.”

Lessons from the Past

Fourth-year student Kevin Byram took the course this fall after a recommendation from a fellow student. “One of the best lessons to be learned from reading or watching stories about doctors is to see how we are represented in the media,” Byram says. “Our patients come to us with preconceived notions of what a doctor is and what we are capable of.”

Byram chose to read Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith, which chronicles the career of a young physician. “It is amazing how a novel written 90 years ago is still extremely relevant,” Byram says. “Today we face many of the issues the protagonist deals with—the importance of bedside manner, commercialism in medicine, and balancing life and work.”

Schmit had the same experience while watching Not As a Stranger, which came out in the 1950s and stars Robert Mitchum. “It portrays a doctor who tries to be a perfectionist in all facets of his occupation but is unable to function well as a human being,” she says. “Throughout medical school, there is pressure toward perfectionism. But what we have to keep in mind is that our patients do not care if we have memorized the latest protocols or are up to date on cutting-edge research; they want a competent physician who cares about them as people rather than as ‘subjects.’”

Fourth-year student Laura Billiet, who took Evans’s class last fall, says she enjoyed seeing “how the idea of a doctor changed over time and how the role of women in medicine changed as well.” In People Will Talk, she says, “the doctor decides to lie to a patient and tell her she’s not pregnant in an effort to protect her from herself because she was so upset when she found out the news. These days, that would be considered very unethical, and I don’t think anyone would consider it, despite the fact that sometimes it may be the most compassionate thing to do.”

From Marcus Welby to Dr. McDreamy

“If you make a movie about what makes a doctor tick today, it would be different than a movie like Not As a Stranger,” Evans says. “That film glorifies the general practitioner, who is not nearly as celebrated today as an ER doctor or a surgeon.

“For a long time, a doctor was always shown dressed respectably in a white coat with a stethoscope,” Evans adds. “Now they’re always in scrubs—and they’re hopping in and out of bed with each other, which reflects a change in the doctor’s status in society. It used to be Dr. Kildare and Dr. Welby, leaders of their communities. Now a doctor is much more likely to be vulnerable—in fact, to be portrayed as much more flawed than many of us really are.”

The medicine practiced in TV shows such as House, M.D. or Grey’s Anatomy is “very much driven by adrenaline,” Evans notes. “Our medical students love to watch these shows because they are fascinated by the dilemmas and intellectual challenges these doctors face. Medicine is always made to seem like a very exciting career, but of course that isn’t always the case.”

Fourth-year student Nirmal Choradia, who says he has “never been one to watch movies of my own volition,” was struck by how far from reality even the most realistic medical dramas will go. “Doctors do not have the kind of power that the public believes, especially since medicine is now such a team-based job.”

While medical dramas remain intriguing throughout medical school, students say that medical reality shows quickly lose their appeal. Schmit says she used to watch Untold Stories of the E.R. and Mystery Diagnosis, but “I just can’t anymore. I see more than enough of that kind of thing in the hospital.”

One thing most students seem to agree on: The absurdist comedy in the TV show Scrubs is hard to resist. “Many people in medicine identify with Scrubs, and I can see why,” says Byram, who notes that the show is loosely based on The House of God. “Sure, the show is goofy, but it deals with issues we face every day, like losing patients, dealing with coworkers, and the hierarchy within medicine. The show uses humor a lot, which we have to use to cope sometimes.”

Docs on the Box

Evans, who doesn’t watch TV “by personal choice,” missed the hit doctor dramas of her own med-school days, including St. Elsewhere and Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman. But even though she has never seen House, she understands why students would be attracted to its portrayal of a blunt, brilliant physician. “He can be everyone’s alter ego,” she says.

|

More Movies In addition to the Doctor in Film, Fiction, and History class, Hughes Evans teaches two other movie-centric Special Topics courses at the School of Medicine, focusing on celluloid (and novelistic) depictions of disease and medical education. |

Although she doesn’t consider herself a film buff, Evans says she does enjoy introducing students to classic movies. “I try to find films that students have not seen before,” Evans says. “I wouldn’t use Contagion”—a 2011 blockbuster about a disease outbreak; “instead I would use a film-noir classic called Panic in the Streets about plague in New Orleans.”

She is always on the lookout for fresh material from Hollywood’s back catalog, though not every old movie about doctors fits the bill. “Sometimes the first time I see them, they’re horrific, just so dated and melodramatic,” she says. “But the second time around, I can find some things to talk about.”

Movies often get the medical experience wrong, Evans says. “They put doctors in situations that are well outside their expertise—like having a general physician do cardiac surgery,” she says. “The technical mistakes are fun to find and laugh about, but whether you’re laughing at it or relating to it, movies are a great way of engaging students in a discussion of the serious issues of medicine.”

Related Articles

Read insights and personal essays from UAB medical students who took Hughes Evans’s Special Topics course on the medical humanities in this article from UAB Medicine magazine.