Simulated Patients Help Med Students Learn People Skills

By Matt Windsor

At UAB's Clinical Skills Center, medical students practice patient communication and diagnosis skills with the aid of simulated patients from the community. Bill Moates is sick for a reason. Several times a year, he adopts an alias, carefully rehearses his symptoms, and tries to convince medical students that there is something wrong with him. Tonight, as the students start to visit his exam room, he has a story to tell.

At UAB's Clinical Skills Center, medical students practice patient communication and diagnosis skills with the aid of simulated patients from the community. Bill Moates is sick for a reason. Several times a year, he adopts an alias, carefully rehearses his symptoms, and tries to convince medical students that there is something wrong with him. Tonight, as the students start to visit his exam room, he has a story to tell.

Moates isn’t looking to score some medication or a free night in the hospital. In fact, he’s fulfilling an essential role in the doctor-training enterprise at the UAB School of Medicine. He is a member of the public enacting the part of a standardized patient, commonly known as an SP, in order to help medical students learn the physical and emotional skills they’ll need to care for real patients.

Story continues after video

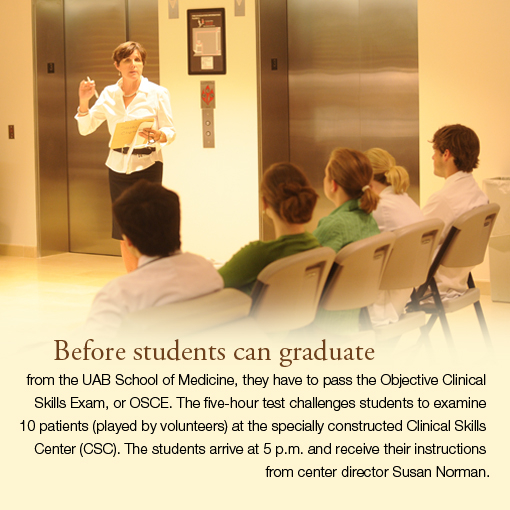

On this August evening, Moates is preparing for a five-hour shift as UAB senior medical students take their Objective Structured Clinical Exam (OSCE). “I’m having a ball,” he says with a grin. The medical students are not so relaxed. A passing grade on the OSCE is required for graduation, and the tension on the third floor of Volker Hall is palpable.

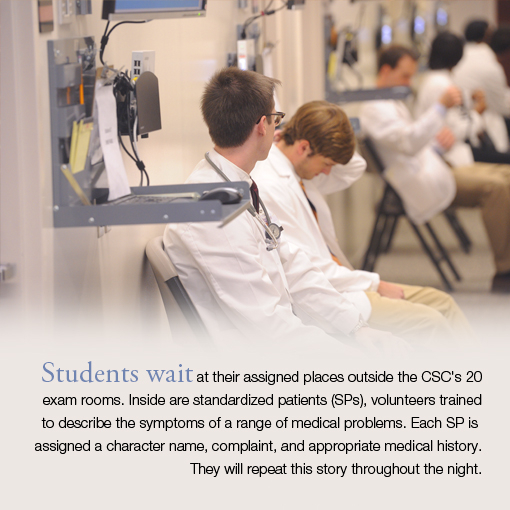

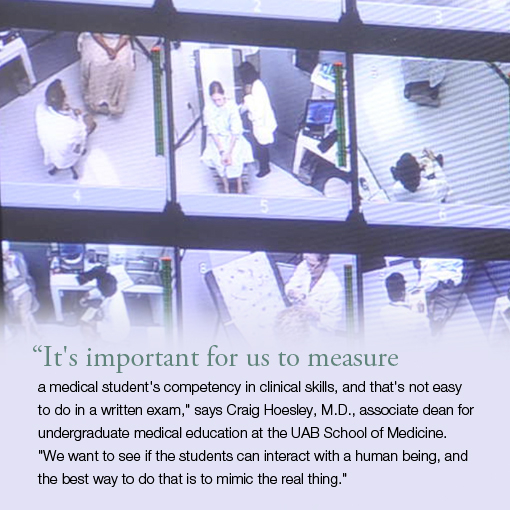

While the rest of the building is given over to lecture halls, research labs, and offices, the third floor looks a lot like a private medical practice—with some special features. There are 20 exam rooms on the floor, branching off two long corridors. Outside each room is a computer terminal and a chair, and sitting in the chairs are 20 medical students, staring straight ahead with expressions of nervous concentration.

A voice comes over the loudspeakers: “Please enter your rooms now.” In unison, the students stand up, knock on the closed doors of their exam rooms, and get to work.

Talk to Me

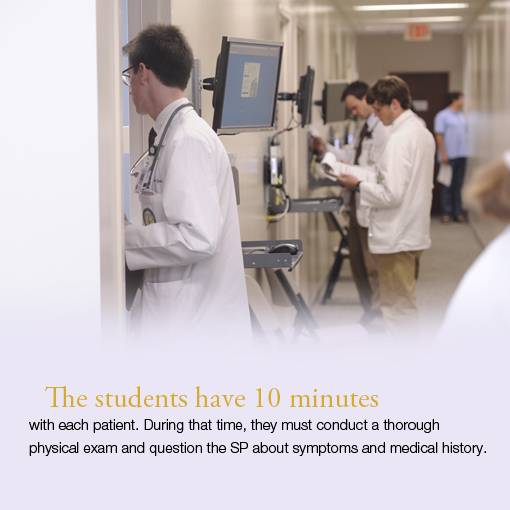

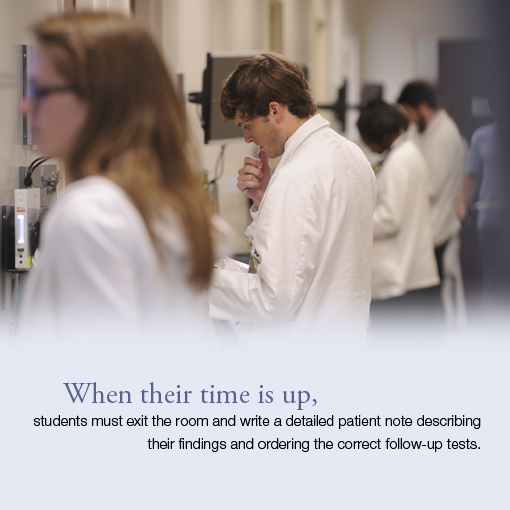

A few hours later, senior medical student Amber Bishop has worked her way around to Bill Moates’s exam room. As he launches into his by now well-practiced story, Bishop’s job is to sift his words for clues, give him an appropriate physical exam, and ask the right follow-up questions. Then she must state the case correctly and succinctly in her notes and order the right follow-up tests. Eighty percent of her grade will be based on her physical exam and interaction with the patient; the rest comes from an evaluation of her notes.

Bishop says she felt well prepared for the test after spending her third and fourth years of medical school learning how to interact with real patients in UAB’s clinics. “Our clinical years are the best preparation for the OSCE, because we truly learn to interact with patients in a compassionate yet efficient way,” she says.

Eye in the Sky

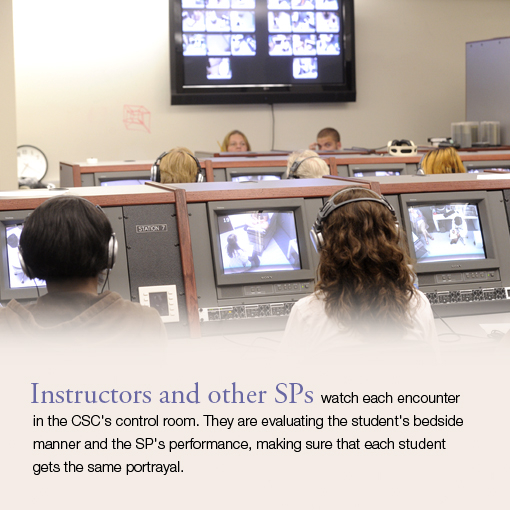

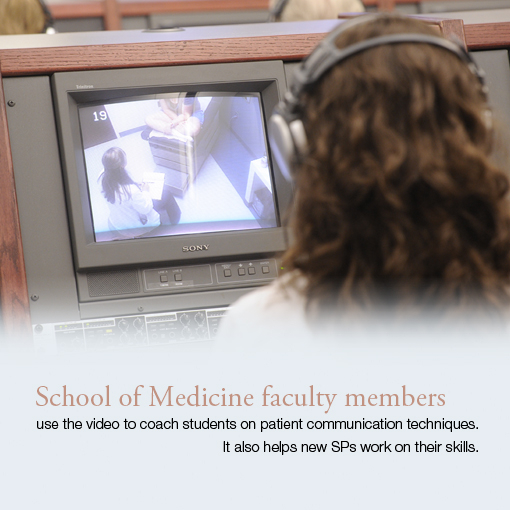

As Bishop starts to talk with Moates about his case, a camera mounted on the wall records every word and gesture. A few dozen yards away, in a room that looks like a cross between a TV studio and NASA Mission Control, Susan Norman takes it all in. Norman is the director of this hive of activity, formally known as the Clinical Skills Center. She trains dozens of volunteers like Moates to accurately portray a range of medical conditions—and to give the same portrayal every time so that no student gains an advantage (or disadvantage) over the others.

|

"You have to pass the OSCE to get through medical school, so the stakes are high,” says Norman. For five hours, she moves through the center like a stage manager, making sure this complex production goes off without a hitch. |

“You have to pass the OSCE to get through medical school, so the stakes are high,” says Norman. For five hours, she moves through the center like a stage manager, making sure this complex production goes off without a hitch. Tomorrow night, she’ll do it all over again.

Testing, Testing

The School of Medicine has been training students through simulated patient encounters for decades. Several years ago, when Volker Hall underwent a major renovation, the school added the Clinical Skills Center as a stage for these encounters, wiring each room for sound and video so that the scenarios could be recorded and replayed as a teaching tool. Because electronic medical records are becoming an indispensable part of modern medicine, the school recently added computer terminals outside each room for students to record patient notes.

Students first encounter the Clinical Skills Center and SPs like Bill Moates soon after they arrive at the School of Medicine. “First- and second-year students in the Introduction to Clinical Medicine course come here in groups of two or three and practice their physical exam and history-taking skills with our SPs,” Norman says. Moates, using a script, helps students work through the questions they’ll need to ask to get a detailed patient history. Then he climbs up on the exam table so the students can practice abdominal exams, cardiovascular exams, musculoskeletal exams, neurological exams, and more. “They need a body to practice on; that’s what I’m here for,” Moates says. Bishop says that the early opportunity to practice her skills and get feedback from the SPs was “very helpful and reassuring.”

As the students move through school, they revisit the Clinical Skills Center for periodic tests to make sure they are ready to enter the hospital full-time as third-years. The center is also used by students from the UAB schools of Nursing and Health Professions and by visiting groups from other universities. This provides plenty of work for Susan Norman and her crew of SPs. The center is “utilized 10 to 15 days out of each month—sometimes more but rarely less,” Norman says. "And we're always looking to partner with new groups to use the facility."

SimPatient

It takes a long time to produce a good fake patient. Each new SP gets a minimum of four hours of training, Norman explains, including a thorough grounding in physical examination skills from Stan Massie, M.D., an associate professor in the Department of General Internal Medicine. The majority of training is done by UAB M.D./Ph.D. students, who have completed the first two years of medical school and are now in the research phase of their education. “Then they’ll spend four to five hours of watching other SPs before we let them work with students,” Norman says.

The SPs are paid for their time, but regulars like Moates say it is really a labor of love.

The SPs are paid for their time, but regulars like Moates say it is really a labor of love. For Moates, it was also a homecoming of sorts. He began his career in the television industry (he was an original producer and director for Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood in Pittsburgh before moving to Birmingham), and worked for UAB’s medical television group for 22 years. “I actually videotaped mock patient interactions for the School of Medicine in the late 1970s,” he says. “After I retired, I was looking for something interesting to do.” A friend who helped set up UAB’s current Clinical Skills Center suggested that Moates might like being an SP. “I talked to a guy the first night I was here, and he said he’d been doing it for 11 years,” Moates recalls. “I thought to myself, ‘Get a life!’ But here it is 11 years later, and I’m still at it. I love it.”

Moates says he enjoys helping to train new generations of doctors. He also appreciates the mental stimulation. “I never get bored,” he says. “I have to get on the top of my game to do this for a whole night.” In fact, SPs like Moates get together in groups of four to give each other a break. While two are in the rooms playing their roles, the other two watch the video feed in the control room. “We see what the other guy is doing, and we may borrow from them or offer some constructive advice,” Moates says.

SPs learn to stick closely to their scripts. “We’re not looking for great acting,” says Norman. “We want to make sure that each student gets the same experience.” But that’s not to say that personal knowledge doesn’t help. “You can’t go off on your own,” Moates adds, “but in the future, if I play a character with chest pains, I’ll really be able to do that well. I’m undergoing all kinds of heart tests right now because I’m having shortness of breath and pain on my left side, so I’m collecting all these tidbits for a future scenario.”

Story continues after slideshow

Private Practice

Despite the stress of the OSCE, UAB medical students say they appreciate the lessons they’ve learned from the Clinical Skills Center. “There’s nothing like practicing interviews and physical exam skills before being thrown into the real world,” says senior Elizabeth Wingo. “When you first start out, there is a lot of hesitancy in discussing medical problems with patients. You ‘know’ a lot about a disease or syndrome, but it’s all from lectures or books.”

Determining whether would-be doctors can effectively interact with patients is a major part of the OSCE, says Craig Hoesley, M.D., professor of medicine and associate dean for undergraduate medical education at the UAB School of Medicine. “It’s important for us to measure a medical student’s competency in clinical skills, and that’s not easy to do in a written exam,” he explains. “A large percentage of the grade depends on whether the student greeted the patient, looked them in the eye while he or she was talking to them, explained what he or she was doing, and asked if they had any questions. We want to see if the students can interact with a human being, and the best way to do that is to mimic the real thing.”

More Information

If you are interested in becoming a Standardized Patient volunteer at UAB's Clinical Skills Center or want to learn more about working with the CSC, contact Susan Norman at svnorman@uab.edu.