Alumnus Aims to Keep Mars Rover Safe

By Matt Windsor

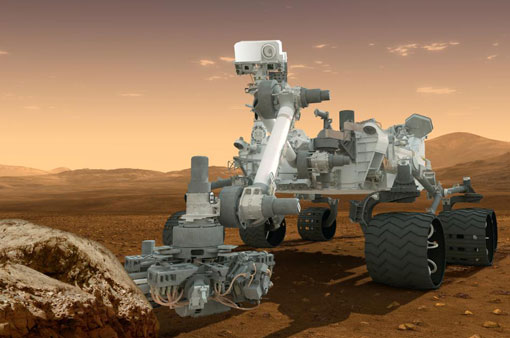

An artist's rendering of NASA's Curiosity rover examining a rock on Mars with its tool-studded arm, which can extend up to seven feet. Curiosity relies on two key instruments on the arm: a drill that collects samples from rocks and a scoop that picks up soil samples. UAB physics alumnus Luther Beegle is part of a team responsible for the safety of both instruments. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

An artist's rendering of NASA's Curiosity rover examining a rock on Mars with its tool-studded arm, which can extend up to seven feet. Curiosity relies on two key instruments on the arm: a drill that collects samples from rocks and a scoop that picks up soil samples. UAB physics alumnus Luther Beegle is part of a team responsible for the safety of both instruments. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

| A |

merica’s latest Mars probe is called Curiosity, but as the car-size spaceship hurtled toward the Red Planet on August 5, Luther Beegle’s 10-year-old son, Ryan, was experiencing a different emotion: anxiety.

Beegle, who holds a master’s degree in physics and a doctorate in astrophysics from UAB, was a little antsy himself. A safe touchdown meant he would finally get a shot at a mission after more than a decade as a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). It would also be a neat follow-up to the Mars rover missions undertaken by his UAB mentor, Thomas Wdowiak, Ph.D., in the mid-2000s.

Luther Beegle is a part of NASA's

Luther Beegle is a part of NASA's

Mars Science Laboratory team,

which is directing the Curiosity

rover in a search for signs of life

on the Red Planet. Above, Beegle poses with the rover pre-launch in NASA's Mars test bed.The Big Dig

“Five minutes before the rover landed, my son came up to me and said he was really nervous,” Beegle says. “He and my daughter, Abigail, have been to the lab many times and saw the rover being made, but it didn’t become real to them until the landing. I gave him a hug and said it would be OK.”

It was. Curiosity landed safely, drawing cheers from the crowd. In a conversation a month later, Beegle was still elated, even though the pressure has, if anything, intensified.

Beegle’s role on this mission is to be something of an interplanetary safety inspector. “I am one of three surface sampling systems scientists,” he says. “We’re in charge of Curiosity’s drill and scoop”—which are crucial to the mission goal of “finding traces of organics and understanding the habitability potential of Mars,” Beegle says. “It’s our job to let the engineers know if it’s safe to drill into something. If the drill fails, then the two analytical instruments can’t work, so we’re very conservative in what targets we choose.”

For the first 90 days of the Curiosity mission, Beegle and the entire team are working on Mars Time. Since a day (or “sol”) on Mars lasts 24 hours and 39 minutes, that means his shift begins roughly 40 minutes later each day. (Beegle and most other team members track the shifting clock using a NASA smartphone app, which has largely replaced the “Mars watches” used by earlier crews.) After three months, “we go to a more reasonable 8:00-to-6:00, seven-day-a-week schedule,” Beegle says. “It sounds horrible, but it’s really not; I’m doing such interesting work.”

Cruise ControlCuriosity is able to travel 100 to 200 meters (roughly 325 and 650 feet, respectively) per day. Over the course of the two-year mission, it is expected to travel around 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) and acquire more than 20 Martian rock interiors for analysis in order to further the understanding of Martian geologic and chemical history. It takes six to eight hours to write the computer scripts that direct the next day’s movements, and 23 minutes for those commands to reach Mars from Earth. |

Blazing a Trail

You could say that UAB coaching legend Gene Bartow recruited Beegle to Birmingham from his native Pennsylvania. “I knew about UAB from the basketball team in the late 1980s and Coach Bartow,” Beegle says. “That put the school on my radar. When I went looking for grad schools, it was one of the several places I applied.” After he visited the campus and met with Wdowiak, he knew it would be a great fit. “I chose UAB over all the rest.”

In 1995, Beegle earned his master’s in physics, adding the doctorate in astrophysics in 1997. “Then I turned in my thesis to the graduate school, bought a new car, and drove out to California,” he says. “I’ve been here ever since.” Unlike many people who end up in the space program, he wasn’t planning this career trajectory his entire life. “But one of the beauties of JPL is that there’s a ton of interesting work going on out here, and I’m constantly getting to explore new things.”

Space Shot

Join the MissionFollow Curiosity on its trek across Mars on the rover's official NASA Twitter feed. And learn more about the "seven minutes of terror" that preceded Curiosity's safe landing in this video. |

At the moment, Beegle is focusing on exploring Mars’s Gale Crater with Curiosity. On a typical day, Beegle pores over the latest data from the plutonium-powered rover for a few hours before “we gather for the technical science kickoff meeting, where we decide what we’re going to do with the rover—which instruments we’ll use, and where we’ll tell it to go,” he says. Next he and his team put in six to eight hours “writing the scripts that tell the rover what to do.” More discussions and long-term planning meetings follow, adding up to a typical 10-plus hour day.

Beegle says he wouldn’t sacrifice a minute, however. And he has even enjoyed a taste of celebrity. Early on in the Curiosity mission, he agreed to help out in the media tent. “I didn’t realize they would put me on the air,” he says. But within five minutes, he was talking to a crew from the English-language Al-Jazeera cable network, and “I did interviews nonstop for three hours—on four hours of sleep.” He has since talked with NPR, Fox News, and a host of other TV and radio stations, and his quotes have appeared in newspapers around the world.

A self-portrait of Curiosity collecting its first Mars rock sample on Sept. 22.

A self-portrait of Curiosity collecting its first Mars rock sample on Sept. 22.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech The Curiosity mission is planned to last at least two years, and Beegle is in for the duration. “Depending on how long the rover remains operational, it could be longer, which would be great,” he says.

Beegle and his graduate mentor Wdowiak still talk regularly, he says. (Wdowiak is himself a veteran of NASA’s Mars program; he operated the Mossbauer spectrometer for the rovers Spirit and Opportunity, the latter of which is still operating on Mars.) “We still bounce ideas off each other,” Beegle says. He also can compare notes with several fellow UAB physics alumni now working in the aerospace industry, although their busy jobs don’t leave much room for in-person socializing, Beegle notes. “We keep in touch by e-mail, though.” Another common bond is The Big Bang Theory—the TV show about a group of physicists living in Southern California. “We argue about which characters are most like each of us,” he says.

Science—and sports—tie Beegle back to Birmingham. “I had a good time at UAB,” he says. “I did a lot of fascinating research, and I still miss the basketball program and Gene Bartow. If he didn’t come and run the program at UAB, my life might have been very different.”

Flight Crew:

|