By Matt Windsor • Illustrations by Tim Rocks and Jessica Huffstutler

In some ways, America’s obesity problem has the simplest of solutions. If we could reduce the calories in our diets and increase the time we spend exercising, we could virtually guarantee ourselves longer lives and billions in health-care savings.

But that’s a big “if.” Despite persistent public health messages, physicians’ warnings, and other outreach efforts in recent years, Americans are heavier than ever. Fresh ideas are desperately needed. Dozens of UAB research teams are engaged in the search for answers, exploring everything from new motivational techniques to a field-ready tool for measuring body fat. Learn more about four of these investigators and their big ideas:

A Better Way for Weight Loss?

Muscle Is Medicine in “Gain to Lose” Approach

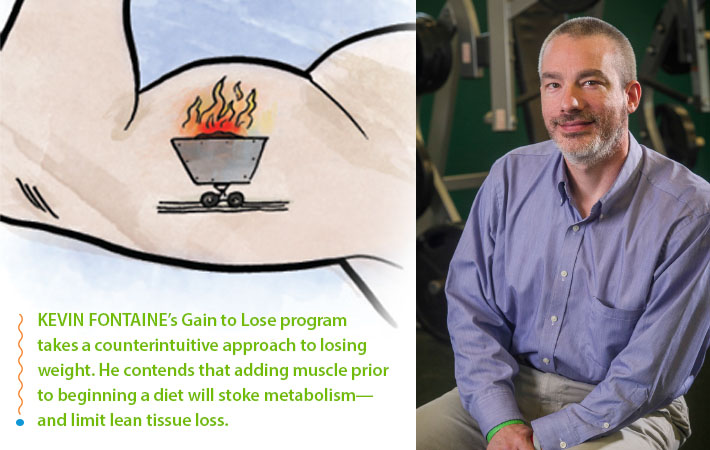

Kevin Fontaine, Ph.D., has an idea for a better way to lose weight, and the professor in UAB’s Department of Health Behavior already has a catchy title: Gain to Lose. He also has some seed funds to develop his idea thanks to the Back of the Envelope Awards, a program in the UAB School of Public Health that acts like a venture capital fund for innovative research proposals.

The conventional approach to losing weight is to “restrict how much you eat and exercise more,” Fontaine says. The problem with that, he notes, “is you tend to get indiscriminate weight loss—you lose muscle and other lean tissue along with the fat.”

Losing lean tissue compromises metabolism. That could be one reason why many people who do lose weight can’t seem to keep off the pounds in the long term. “The question we’re trying to answer with Gain to Lose is, can you produce discriminated weight loss?” says Fontaine. “We want to focus on losing body fat, not just weight.”

Gain to Lose doesn’t start with diet, but with increasing muscle mass. “Muscle is medicine,” Fontaine says. “It burns calories, stokes metabolism, and enhances overall physical functioning.”

The initial stages of Gain to Lose will “focus on exercise to promote a mild increase in muscle and lean tissue,” Fontaine says. This muscle will act like a bank account for when the dieting begins. “You’re trying to increase savings so that when you start withdrawing, you will be ahead of the game,” he explains.

Just any old exercise won’t do. “Aerobic exercise, like running or walking, certainly has its place, but I want to focus on the particular types of exercise that promote or enhance muscle,” Fontaine says. That includes things like weight training, he notes. “But I’d like to eventually develop a protocol where people wouldn’t need to go to a gym—they could do the exercises using their own body weight,” such as sit-ups, chin-ups, or pull-ups.

In the diet phase of his plan, Fontaine will focus on restricting carbohydrates such as sugary snacks, bread, and pasta. “These create an increase in insulin, which promotes fat storage,” he says. “We’ll have people gradually decrease carbs, which should produce fat loss but preserve or at least slow muscle loss at the same time.”

The first step will be to hold small trials to “flesh out the protocol” in preparation for a large, randomly controlled study in the future, says Fontaine. His goal is to keep the plan slim and trim, emphasizing things people can do on their own. “I’m in public health,” he says. “I always want to think how we can make interventions simple so that they can be available to and used by as many people as possible.”

Fitness to GoNeed some coaching on fitness and nutrition? The UAB Campus Recreation Center brings experts, classes and more to groups and workplaces across the Birmingham area through its Wellness Catering program. Learn more about the initiative and discover five ways to stay active at the office. |

Snap Fat

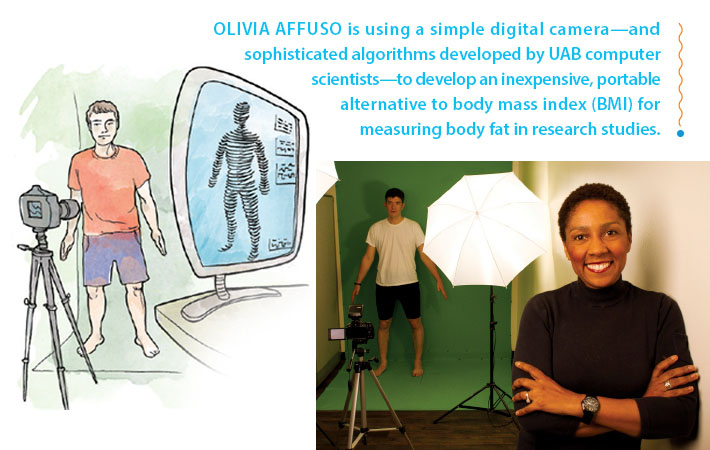

Photobody Study Examines High-Tech Replacement for BMI

The old saying in Hollywood is that the camera adds 10 pounds. But UAB obesity researcher Olivia Affuso, Ph.D., thinks that the right software could transform even a basic digital camera into a very accurate judge of body fatness.

Her study, appropriately named Photobody, is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The country’s research heavyweight is seeking an inexpensive, portable, and simple way to measure body fat in large-scale epidemiological research studies. Affuso, along with co-investigators David Allison, Ph.D., and Chengcui Zhang, Ph.D., is developing just such a solution.

Body fat is a crucial measure of a patient’s health, or the effectiveness of a treatment. Most studies use body mass index (BMI) as a proxy for body fat because it has several advantages. For one, it’s a fairly simple calculation that only requires two inputs: a participant’s weight and height. Research also shows that BMI is a good gauge of a person’s risk for everything from heart disease to breathing issues and some cancers. But “BMI has its limitations,” Affuso explains. “If you are very muscular, you can fall into the overweight category even if you are normal weight. Or it can underestimate body fat in people who are normal weight but have low muscle mass.”

To get more accurate readings, investigators at UAB and elsewhere turn to DXA (pronounced dexa) scanners. “The problem is that a DXA scanner is well over $100,000, so not many places outside of major universities actually have one—and it is not portable without a truck,” Affuso says.

But trained body composition assessors are often able to guess a person’s body fat with a high level of accuracy just by looking at them, Affuso explains. That gave the UAB researchers an idea. “We’re using techniques with foundations in photogrammetry, as well as some topography, to train a computer to recognize body fat,” says Affuso. In her lab/photo studio at the UAB School of Public Health, Affuso’s team takes three pictures of volunteers aged 6 to 80. Advanced computer algorithms designed by Zhang then analyze the photos and spit out an assessment of the person’s body fat percentage and compares that information to the DXA. The system is now covered by a patent.

The goal is to “come up with an easy, portable, inexpensive, easily replicated way to assess body composition,” Affuso says. Researchers could take the system into the field—to do long-term evaluations of body fat for an obesity intervention at a school, for example, “instead of bringing all the participants in here, as we have to do now.”

The technology also has clinical applications, Affuso adds. “This would be a great way for physicians to help their patients look at weight change over time.”

Feedback Loop

Social Networking for Behavior Change

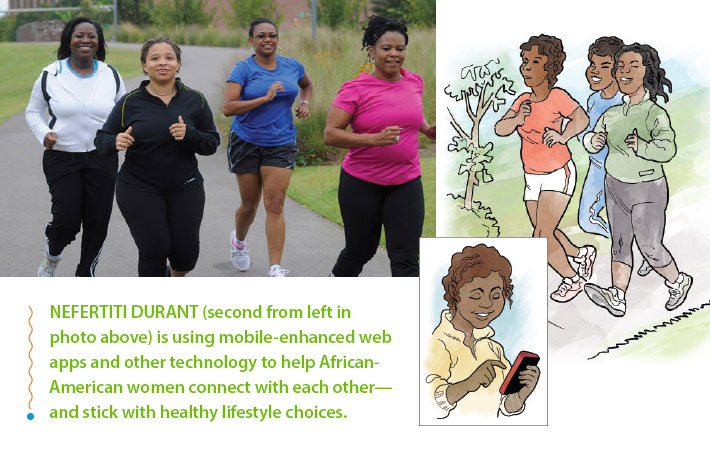

Nefertiti Durant, M.D., wanted to know how the Internet could help young African-American women lose weight. To find out, the UAB adolescent medicine physician is taking an approach straight out of Silicon Valley: crowdsourcing.

In a series of studies, Durant is refining a Web-based, culturally relevant tool to help participants—African-American women ages 19 to 30—stick with a moderate walking program. Her site lets participants track their diets and physical activity, find healthy recipes, and discuss their successes and setbacks on message boards.

“We had very good findings in phase 1,” says Durant. “We showed an increase in moderate physical activity of 81 minutes,” along with an increase in HDL, the “good” cholesterol. The biggest problem was “keeping the young women in the study,” Durant says. Almost half of the original participants dropped out during the six-month project. “But of those who did stay in, 85 percent enjoyed the tool and the program in general.”

Styles Matter

Durant set about revamping the project for a second phase, using her original participants as a focus group. Hair turned out to be a major exercise obstacle for the young women, Durant says. The sweat from a workout can quickly destroy a salon-fresh style, especially chemical-intensive “relaxed” hair. “Everyone wants to look nice, particularly women at this age,” Durant says.

Durant added a blog on hair care advice, including entries on special headbands and shampoos to preserve hairstyles. She also addressed another concern: photos. The original study site featured pictures of trim women exercising. “They wanted to see women of more diverse shapes and hairstyles,” Durant says. “They said, ‘We want to see people like us, not models.’” She scheduled a photo shoot at Birmingham’s Railroad Park and added images of a wide range of women working out. She also optimized the site for viewing on smartphones—a must-have feature for this age group, Durant says.

Preliminary data indicates the changes made a big difference. “We again saw a significant increase in moderate physical activity, but this time we had 80 percent retention,” Durant says. “We also saw increases in participants’ reported social support.”

The participants were outspoken in support of Durant’s requirement that they connect by blogging and posting messages about their experiences. “They had formed real bonds,” Durant says. “Some posted messages several times a day. They would write some very touching things. It was a safe space to tell their story with people who understand.” The redesigned website is now open to the public at www.loveyourheartaha.com.

Tell It Like It Is

In a new project, tentatively titled Fit Heart Narratives, Durant is exploring the power of storytelling as a motivational tool. She plans to create a series of videos in which participants tell their stories of battling obesity.

The idea builds on a successful project led by former UAB faculty member Jeroan Allison, M.D., who filmed patients with hypertension talking about their successes and failures in keeping their blood pressure under control. Patients who saw the videos in addition to their usual doctor’s visit had better outcomes than those who spoke to a doctor alone, Durant says. The concept is now being adopted nationwide.

“People always talk about the successes,” Durant says. “That’s what you hear in the weight-loss ads on TV. But our participants have said, ‘We want to hear the beginning, the middle, and the end. We want to hear it all, not just the good stuff. We want to know how you overcame the struggles.’”

Text This, Not That

One of Durant’s colleagues in the Department of Preventive Medicine, Jasmine Pagan, M.D., is studying text messaging as a motivational tool. Several women in Durant’s original study agreed to brainstorm texts that could help peers push through obstacles to working out. “They each wrote the messages they would like to hear,” Durant says. “Then my staff texted them out over a couple of weeks, and the girls re-rated them.” After several iterations, “we now have a bank of messages that address shame, hair problems, feeling like you don’t have enough time to work out, and more,” Durant says. She and Pagan plan to keep the writing and review process going with future groups.

Durant hopes to combine all of these insights into a single study in a large population. Her goal is to create a research-tested tool she can use in her own practice to connect with patients—and connect them with each other. “They know what they need to do,” she says. “We just have to find a way to nudge them.”

Pump It Up

Bringing Multisite Trials to Exercise Medicine

Marcas Bamman, Ph.D., wants to take exercise research to a whole new level. “While we all know that some exercise is good for us, there are a number of scientific questions that have yet to be answered,” says Bamman, director of the UAB Center for Exercise Medicine (UCEM). “What’s the right exercise dose for a patient with heart disease versus someone with Alzheimer’s, or a patient who has just had a joint replacement? How often should they exercise, and at what intensity?”

Studies to answer those questions are already under way at UCEM, Bamman says, but no single site can generate the data needed to make definitive recommendations for every type of patient. Bamman illustrates his point by citing a recent UCEM study, in which investigators tested a hybrid workout regimen for patients with Parkinson’s disease. “Two things are happening in Parkinson’s that we haven’t much of an answer to before,” Bamman says. First, patients have an “increased perception of fatigue—they just don’t want to do much,” he explains. Second, their mitochondria—the powerhouses of the cell—have reduced capacity, not just in the brain but “all over the body.”

Bamman’s team designed a workout that would improve patients’ mitochondrial capacity while reducing their perception of fatigue. “It combines strength training with high-intensity intervals so that patients rest very little during the exercise sessions,” which last about 45 minutes, Bamman says. By the time fatigue takes over, the sessions are done. In a pilot study, Bamman notes, “we had really good responses.”

But what if there was something about the participants’ ethnicity or genetic makeup that skewed the results? It’s possible that the UAB investigators just know how to push patients to perform harder, where other, less-experienced instructors might fail. “Not everyone responds the same way to certain drugs or devices, and exercise falls into that same category,” Bamman says.

To get truly definitive results, Bamman continues, exercise researchers need to follow the standard practice for drug treatments and expand into collaborative multisite research. He’s leading the way by founding a national exercise clinical trials network known as NExTNet, with UAB as the coordinating center. NExTNet already has 48 member institutions, and a first meeting is scheduled to take place at UAB in February 2014.

Adding more patients, and therefore more statistical power to the results, is one benefit of such a network, Bamman says. “But another major one is that you can standardize the conduct of the treatment itself,” he adds. “Today, one site will prescribe a three-day-per-week exercise regimen, with a very particular intensity or type of equipment.” And even though on the surface the regimens seem the same, “another site may define a very different intensity, or use different equipment,” potentially skewing the results, says Bamman. “Just like any trial, the first step is to make sure we collect data the same way.”

Bamman’s UAB team recently submitted a two-site exercise trial with a group from the University of Kentucky, which will take advantage of the NExTNet infrastructure. “We have visited each other’s facilities and have matched equipment and testing procedures, so we’re not combining apples and oranges,” Bamman says. “Our goal for the network is to stimulate interactions that will catapult this field forward into the treatment realm with definitive exercise prescriptions.”

Pioneering a Team-Based Approach to Weight LossExperts from the UAB Health System, School of Medicine, and School of Health Professions have joined forces in a new, team-based approach to address Alabama’s obesity crisis. The UAB Weight Loss Medicine program, the only one of its kind in the Southeast, builds on UAB’s successful EatRight approach, which includes physicians, dietitians, behaviorists, and exercise trainers to help participants achieve a goal weight. The program will also work with patients to prevent excessive weight gain during post-injury rehabilitation, breast cancer treatment, and other high-risk conditions. Learn more at www.uabmedicine.org/weightloss. |

Get Involved

• See if you are eligible to participate in a UAB clinical trial.

• Give something and change everything for UAB exercise and weight-loss research.