Building a Game to Fight the Rural AIDS Epidemic

By Matt WindsorComfort Enah, Ph.D., a researcher in the UAB School of Nursing, can't build a time machine to help teens avoid making bad decisions in the future. So she's creating the next best thing: a video game.

Working with a team from the UAB School of Engineering, Enah is crafting a simulation of the challenges of modern teen life—including social media shaming, drug and alcohol use, dating boundaries, and the wildfire spread of misinformation on the Internet. The goal is to slow the HIV epidemic among adolescents in the rural South. Enah's dream, if the game proves effective, is to take it to the even more hard-hit communities of sub-Saharan Africa, where she grew up.

Maturity without Maturity

Over the past century, puberty has been arriving earlier and earlier, which means that “teens are spending longer and longer periods with bodies that are sexually mature and brains that aren't yet capable of anticipating the long-term consequences of their actions,” says Enah, an assistant professor in the Department of Nursing Community Health Outcomes. “They need to practice their responses to those risky situations, and games are a way to do that in private and as often as necessary.”

Enah wants to create a safe space in cyberspace—an adventure game that gives high-risk teens and pre-teens the chance to rehearse the challenges they'll face—and visualize the results of their choices decades down the line. The project is funded by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research.

To succeed, her game can't be lame. “No one wants to play an ‘HIV prevention game,’” Enah says. “We have to embed the messages as part of the play experience itself.” She has teamed up with the School of Engineering's Enabling Technology Lab, which has programmers capable of building a game with the industry-standard Unity software, and an artist with the skill to make it come alive. Enah has also recruited a crew of hard-to-please beta-testers: dozens of adolescents living in Alabama's Black Belt, which has been hit hard by HIV.

Left Behind

The South as a whole accounts for 45 percent of new cases of HIV/AIDS in the United States and nearly half of all HIV/AIDS deaths. African-American teens are particularly vulnerable; they make up only 17 percent of the American adolescent population, but accounted for 68 percent of new AIDS diagnoses among that group in 2009.

Most research and HIV education efforts aimed at teens have focused on urban areas, Enah says, while rural youths have received little attention. She and colleagues addressed that with a paper in the Journal of Psychosocial Nursing in February 2014, in which they documented a mix of stigma, denial, and misconceptions among teens in several counties in Alabama's Black Belt region. “Participants said things like, ‘People just need to know if you take an antibiotic [against HIV], you'll be fine,’” Enah says. Nearly half of the participants mistakenly thought that a vaccine for HIV is available.

But the biggest problem may be one these teens share with their fellow adolescents around the world: “They just really don't think they are at risk,” Enah says. “They think it is somebody else's problem.” Traditional public health HIV education programs haven't been very effective with teens, Enah points out. “For six months, maybe you get some effect, but you quickly lose their interest,” she says.

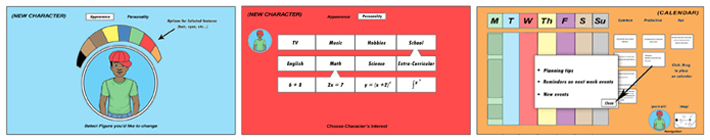

Early graphic concepts for the game from the storyboards created by Comfort Enah and the design team at UAB's Enabling Technology Lab.

Early graphic concepts for the game from the storyboards created by Comfort Enah and the design team at UAB's Enabling Technology Lab.SimTeen

So Enah is taking an alternate path. In a series of meetings in towns across the Black Belt, she has gathered evidence that a game-based intervention could hold the interest of rural teens. She found that video games are a popular outlet for youths who have few other entertainment options, and that most have access to computers and gaming systems. Enah is using the feedback from these focus groups to design the first draft of the game. When that’s ready, she'll take it to her testers and let them tear it apart, then redesign the game based on their criticisms, and so on.

The game's content will be “embedded in a series of challenges,” Enah says. “For example, you'll face a situation where you are with somebody who is desirable—at a football game behind the bleachers—and they want to go further than you want to go,” Enah says. “How do you handle that?”

Players will have a range of options to choose, “and the game will keep track of their decision-making,” says Enah. “All of this will add up. If they are mostly risky with their choices, then their outcome is not going to look that great.”

Periodically, players will “get to peek into the future and see the impact of all these little daily decisions on their lives; mostly on their health, but also on their success in life,” says Enah. “Cognitive research has demonstrated that teenage brains aren't fully capable of evaluating the risks of a situation,” she notes. “We want to show them the consequences so they realize that health and success in life go together.”

The game will be tailored to the player, Enah adds. A 12-year-old girl who is sexually inexperienced will receive different messages than a 16-year-old boy who is sexually experienced, for example.

Peer Pressure

The game will also help players evaluate peer advice, both good and bad. Based on her own research and many other studies, “it is clear that peer norms—or your perception of peer norms—are one of the biggest drivers of whether kids engage in risk behaviors or not,” Enah says. “We really want to tackle that.”

At the game's decision points, players will often “get input from their peers,” Enah explains. “Some of those peers will give them advice that is safer for their health, others will offer opinions that are very risky. The players get to decide what to do based on all that they have heard.”

Players will also have the chance to correct misinformation they get from their peers—to explain that antibiotics in fact have no effect on HIV and that there is no vaccine to cure AIDS. “If they don't have that information, we are going to give them the option of seeking out a mentor in the game,” Enah says.

International Appeal

If the game is successful, Enah hopes to expand her model overseas. “I come from sub-Saharan Africa, and there's a big need there, so I always have that in the back of my mind,” she says. The millions suffering from HIV “aren't just numbers to me. I have classmates, cousins, neighbors that have died from this disease. And from a very early age, I felt an obligation to help. ‘If we can prevent this disease,’ I thought, ‘why aren't we doing more?’”

Exporting the game would require some cultural tweaks—swapping a football game scenario for a soccer match, for instance—but the UAB team is purposely designing the game to be as flexible as possible. “In Africa, many people don't have computers, but everyone has a mobile phone,” Enah says. “We would have to build the game around a phone interface. We would also have to change some of the wording and situations, but the mechanics of the game could stay the same.”

The ultimate message for players, wherever they live, “is that what you do now has implications for your future,” Enah says. “We're telling them, ‘Yes, there are limitations in your environment, there are things you may not have control over, but there are some things you can control, some decisions you can make that might enhance your potential for success in the future.’”

This article originally appeared on The Mix, UAB’s research blog.

Get Involved

• Give something and change everything for researchers in the UAB School of Nursing.