In the waning moments of an Australian winter day last July, Alan Franks ended up surrounded by curious kangaroos. Franks, a filmmaker, assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies and director of the department’s broadcasting program, is attracted to ecosystems in danger and the people fighting to preserve them.

Nearly four years after the start of the megafire that killed most of their predecessors at Rae Harvey’s Wild2Free wildlife sanctuary south of Sydney, Franks found himself with a crowd of inquisitive kangaroos sniffing his camera, and another hugging his leg. “When I first arrived that morning, the adults were out at the treeline,” Franks said. “There had been so much distance between me and them. But as the day progressed, they started coming in, and then they were all around me.”

Franks is no stranger to immersive nature filmmaking. He has searched for Spanish shipwrecks on the floor of the Gulf of Mexico and floated rivers in Malawi in pursuit of hippos. His travels have taken him to an uninhabited island at the edge of the Great Barrier Reef and into the American west, where he was a researcher and assistant editor on the series “America the Wild.”

But his work in Australia is particularly close to his heart: bringing the country’s beautiful but fragile ecosystems to life in a way that encourages viewers to get involved in the efforts to save them. In summer 2023, Franks was finally able to return to Australia, where he attended the film program at the University of Sydney on a Fulbright fellowship in the late 2000s, to pick up a project derailed by COVID. Soon after the devastating impact of the Australian wildfires became clear in fall 2019, Franks applied for and received funding from the UAB Faculty Development Grant Program to document the aftermath. Before they were over, the fires of what Australians call the Black Summer of 2019–2020 had burned more than 46 million acres and affected an estimated 3 billion animals.

He planned to travel in summer 2020, but COVID and the Australian government’s strict quarantine and travel restrictions delayed the trip until last year. In the meantime, his project, called “After the Fires,” has changed somewhat.

“The original idea was to film the devastation; now it is devastation plus inspiration,” he said. Harvey, owner of the wildlife sanctuary, lost nearly all her kangaroos and had to be evacuated by small boat from the water’s edge to save her life. Today, she has rebuilt the sanctuary. While he was in Australia for two months last summer, Franks also interviewed a retired professional runner, Erchana Murray-Bartlett, who set a record for the most consecutive marathons run (150) by covering the distance from the country’s northernmost point at Cape York to its southern reaches in Melbourne, 26.2 miles at a time. The goal of Murray-Bartlett’s “tip to toe” feat was to raise awareness of plants and animals at risk for extinction and to raise funds for the Wilderness Society, which preserves wilderness areas. Franks also talked with researcher Chris Dickman, Ph.D., who documented the fires’ web of effects on animals from koalas and kangaroos down to insects and lizards, and Danielle Celermajer of the University of Sydney, author of a book on the fires called “Summertime: Reflections on a vanishing future.”

COVID frictions sapped much of the momentum for change that had built up in Australia in the aftermath of the fires. “But looking at coming weather patterns, once the higher rainfall levels they have seen in recent years stop, there is concern that this may all start again,” Franks said. And as North Americans saw last summer, megafires are not only an Australian phenomenon. While Franks was filming Down Under, American skies were darkened by vast fires in Canada. “Big picture, I would like to use these stories as a teaching tool for other parts of the world — sharing experiences and sharing perspectives,” Franks said.

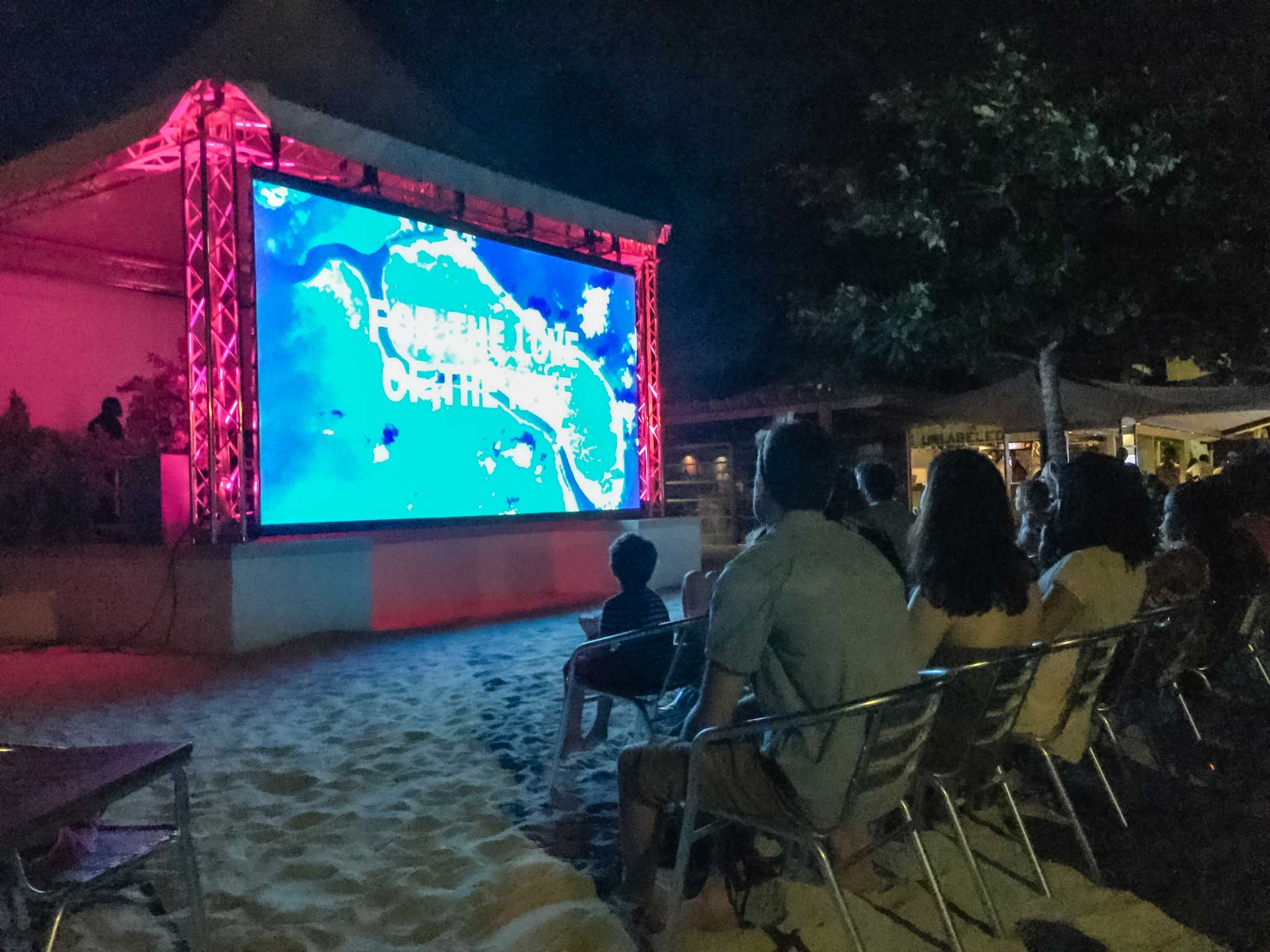

In an earlier film, “For Love of the Reef,” Franks interviewed Iain McCalman, Ph.D., of the Sydney Environment Institute, author of “The Reef—A Passionate History, from Captain Cook to Climate Change,” and asked a question: Why should people care? “When we persuade ordinary people about the importance of the reef, we also have to address their feelings,” McCalman said. “Why should we care? You asked that question. We care because it is unutterably beautiful.”

Now, Franks has a new question for his subjects: Do you still have hope? “The responses ranged dramatically,” he said. “Some people were feeling quite despondent. But for most people, there is hope — not a blind hope that things will work out, but hope that there are people who care enough to try to enact change.”

Storytelling that makes the case for action is a “balancing act,” as Franks explains to students in the broadcasting program. “You want to convey that this is not a lost cause, but you don’t want to be so optimistic that it frees the public from the need for action,” he said. “You have to show that this is a pressing, urgent matter to consider and understand the steps we could take to change. But we also do want to convey that there is still hope as long as there are people who are mindful of those things.”

Franks is part of a long line of Blazers. He is the third of six Franks brothers to graduate from UAB, although he did not major in broadcasting. He had started making videos in high school but also had an interest in science and math that led him to engineering. He graduated with a degree in civil engineering in 2007, along with minors in math and film. “I had enough credits to double major, but UAB did not have a film major at the time,” Franks said. He was interested in environmental topics as an engineer, too, “but eventually I realized I liked talking about it more than practicing it,” he said. “I decided to pursue the film side.”

He received a Fulbright scholarship after graduation to study filmmaking at the University of Sydney. Then, after some time working as an engineer in Birmingham, he discovered an MFA graduate program in Science and Natural History Filmmaking at Montana State University that was specifically geared toward students with STEM backgrounds. “I get to talk about topics that I think are important to explore and can continually learn new things,” he said.

UAB’s broadcasting program includes training in traditional television production in its studio in the Hulsey Center, but the evolution of the field means that students also learn to produce live streams and explore the growing number of avenues for sharing their storytelling. “Over the past decade-plus there has been a lot of blurring of the lines between media,” Franks said. “There are so many avenues to explore, including all the places across the country that are incorporating media in their internal and external communications, including universities, museums, government departments and more.”

Franks’ film “For Love of the Reef” played at several international film festivals, including a screening in Barbados, and won a national award from the Broadcast Education Association and a Telly Award in 2019. Franks is now editing the material from his Australian trip with the goal of having a cut ready for the presentations that Faculty Development Grant Program awardees deliver in the fall. “Then I am looking at niche film festivals around the world with nature or environmental focuses,” he said. “There are some large ones in Australia, Europe and North America. Ultimately, it will end up online after the festival runs and then I plan to develop a home for all of these separate videos. I really consider this a part of a series that started looking at stressors on the Great Barrier Reef and then moved to a focus on the inland ecosystems of Australia. Hopefully, I will be able to go back and continue this series by looking at other stressors on those environments.”