Adam Stermer has been thinking a lot about polyester lately—specifically, how to drape more than 5,000 square feet of it over the façade of the Alys Robinson Stephens Performing Arts Center (ASC) without destroying the structure. “The wind drag created by one sheet of this tremendous amount of fabric would tear the building apart in a mild breeze,” says Stermer, the ASC’s technical director. “So our seamstress spent a week creating eight separate panels, using our largest stage as her workshop.”

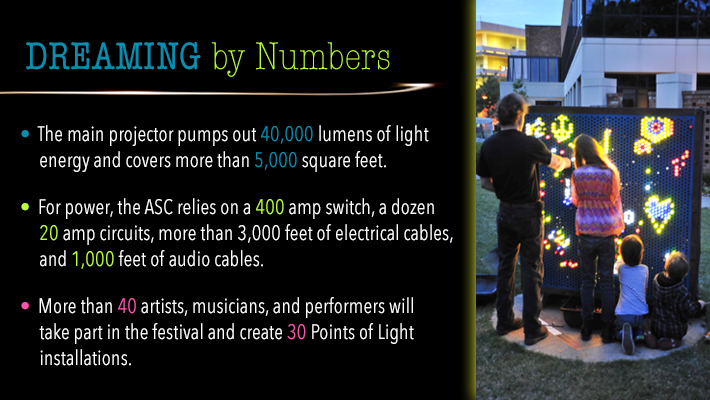

Once unfurled, the luminous white fabric will provide a bright backdrop for Light Dreams, the ASC’s nighttime celebration of Birmingham’s artistic and technological creativity. The free, public event returns for its second year on May 8, 9, and 10, 2014, with new dimensions: 3-D digital projections, virtual reality, an expanded parade, and more than double the number of glowing, smoking, misting, mesmerizing installations created by 40 local artists.

Beyond the polyester puzzle, organizers must solve other logistical challenges, such as wrangling more than a half-mile of cable and securing thousands of 3-D glasses in time for the festival. But ASC corporate board chair Theresa Bruno, who also is president of THB Inc. and co-chair of The Campaign for UAB, eagerly embraces the irresistible opportunity to bring something new and novel to the city. “Along with presenting well-known performers and performances, we want to produce original works for Birmingham that press the edges of how we define art today,” she says. Light Dreams is an example of “living art—art that belongs to an audience in the moment and never takes the same form again. There’s something really powerful about that.”

Light Dreams was inspired by the large-scale, outdoor digital-projection shows that have been popular in Europe, says Jessica Simpson, the ASC’s artist programming consultant. The ASC also opened the event to local artists, challenging them to play with light in sculpture, music, and dance. Last year, more than 2,000 visitors showed up to watch giant digital frogs leap from the façade, marvel at digital dancers, challenge an interactive video game, and explore a grove of glimmering artworks, among other wonders.

“Within an hour of the event starting last year, person after person kept telling me that we have to do this again,” Simpson says. Planning for the 2014 edition began almost immediately.

Jean-Jacques Gaudel in his studio

Jean-Jacques Gaudel in his studio

Pixel Perfection

Gaudel, a French native who arrived in Birmingham 40 years ago, taught himself how to make the digital magic after seeing videos of similar European shows. Those productions involve “architectural mapping,” or projecting a video image of a building onto that building, matching the architecture precisely, and then distorting the image to appear as if the building is falling apart or morphing. Gaudel’s animation uses similar technology, but “it tells a story,” he says. “I’m interested in old things, in textures and colors, more than just light blobs that move around.”

It’s a personal story as well. Light Dreams “is my world,” Gaudel says. Many of the intriguing objects featured in his video actually line the walls and bookshelves of his home. “I have photographs of everything in the house, which gives me a huge library of images to use,” he explains. Those, along with images gleaned from the Internet, reside in meticulously organized folders on his computer—a glimpse reveals files dedicated to balls, bats, books, bottles, and bugs, just to name a few.

Creating the 20-minute “Artista Somnia” has taken at least 800 hours, plus another couple of hundred hours to reformat it for anaglyph 3-D, Gaudel estimates. He works primarily with Adobe After Effects and Adobe Premiere, with his four computer screens dividing each scene into its parts: views from different angles, effects, a timeline, and so forth. Some sequences have up to 400 layers of images and animation and can take more than 65 hours to render into video format. “One idea and image brings another,” he says.

“As far as I know, a full anaglyph 3-D architecturally mapped projection on a large building hasn’t been done anywhere in the world,” Gaudel says. “I’m sure people have thought of it, but it takes a lot of experimenting to get it to work.” Essentially, Gaudel has created animation from two views—the right and left eyes—which will merge when the audience views the projection through its 3-D glasses. He also reworked the digital elements for “deep 3-D space,” so that when a frog hops off the ASC’s façade, for instance, the depth and distance of its leap are magnified for the viewer.

To test his creation, Gaudel projects it onto a scale model of the ASC’s façade, which he built on the back wall of his studio. He’ll get one opportunity to preview parts of the show on the actual building on the night before Light Dreams debuts. “Last year, our big worry was lining up the two projectors we used for the show,” Gaudel recalls. “If the projectors aren’t perfectly aligned—if they’re one pixel off—then the image gets fuzzy quickly.” For this year’s 3-D version, the ASC has secured a single projector, and Gaudel predicts “the effect will be quite striking.”

After a year of viewing the animation on computer monitors and models, Gaudel looks forward to seeing his masterpiece dance on a four-story screen above a curious audience. He’s also working to complete another innovative project that will transform the ground beneath the crowd into yet another surface for 3-D digital projections. “I want them to know that Birmingham has cutting-edge artists and engineers who are creating things that we haven’t seen before,” he says. “We’re trying to put them on the map.”

Clockwise from top left: Eva Dennis, Mike Brascome, Andrew Hyde, and Corey Shum in UAB's ETLab

Clockwise from top left: Eva Dennis, Mike Brascome, Andrew Hyde, and Corey Shum in UAB's ETLab

Engineering Creativity

Light Dreams gives these engineers a chance to play and show off their skills, says ETLab technical director Corey Shum. “We like showing people that virtual reality isn’t just something in a movie,” he explains. “We want to convey the capacities for interactive, immersive media.”

The ETLab is finalizing several projects for this year’s event, including a kiosk where visitors can put on an Oculus Rift virtual reality headset and discover the sights and sounds of new worlds developed at UAB. The festival marks the first time that the ETLab has brought this technology outside for the public to try. Last year’s popular interactive Pac-Man game also will return in a supersized format. And its creator, Mike Brascome, a system analyst in the UAB School of Public Health, is working on an attraction that combines the Oculus Rift with the Microsoft Kinect to enable guests to fly like a superhero through a cityscape.

“We have an infrastructure where we can throw together new ideas very quickly,” often using bits and pieces of programming designed for other projects, says Shum. “But making it into something beautiful and emotive takes time.” Between their other UAB projects, Shum, Brascome, and their colleagues—including Eva Dennis, a 3-D media designer; Scott Wehby, a research technician in the UAB School of Nursing; and Andrew Hyde, an audio programmer—have spent months planning and programming. In fact, they’re likely to parse pixels until the final moments.

But that tight schedule is OK with Brascome. “Extra time is one of the worst things on a project like this,” he says. “Last year, the day before the event, I had finished the Pac-Man game but started tweaking the graphics. Suddenly, Pac-Man started going through the walls. I fixed it with just hours to go.” The public’s reaction was worth that last bout of anxiety, he adds. “Kids wanted to play the game all night. I was having a ball.”

Shum hopes that encouraging the community to experience virtual reality for itself will help people feel more comfortable with the technology—which will radically change the way we communicate in the near future, he predicts—and recognize UAB’s contributions to the field. Light Dreams could also be the spark that inspires a new generation of imaginative thinkers to consider UAB’s School of Engineering, he adds. “For this work, we need people who cross the boundary between art and engineering—who enjoy both the creative and programming aspects,” he explains. “I want potential students to think this is cool.”

Smoke, Mirrors, and Mist

It gets even trickier when you add water. Using a combination of plumbing materials and sprinkler-system components, Cole, along with Tony Rodio and Christophe Nicolet, created a water-mist projection screen for last year’s event. With Gaudel’s help, they have now enlarged it to 12 feet in diameter, creating a space where ethereal “living portraits” will appear. The finished piece will be one of 30 Points of Light installations arrayed around the ASC. “The screens took a few weeks to envision, design, and construct,” says Cole, who received her commercial photography certification from UAB. “The visual content of the projections has evolved over time and through experimentation. It’s hard to figure the total time involved, especially when you factor in the incalculable hours of pre-visualization and daydreaming.”

The 40 Birmingham artists participating in Light Dreams began work soon after last year’s event. Each month, they gather to discuss projects, share feedback, and brainstorm. “We’re encouraging the artists to do things they’ve never attempted before,” says Simpson. “Everyone is building larger or more complex installations”—some involving smoke, fire, mirrors, and bicycle reflectors in addition to water vapor, she adds. Students in UAB’s Advanced Sculpture courses, taught in the Department of Art and Art History by visiting assistant professor Stacey Holloway, are planning an ambitious piece that resembles a circus freak show tent. Motion sensors inside will light up sculptural interpretations of the students’ own mysterious dreams and daydreams.

People throughout the community are nurturing their own creative spark through ArtPlay, the ASC’s education and outreach initiative. Children and adults can make lighted costumes for the parade in a daylong workshop. Elementary through high school students will learn to become VJs—and then use their newfound knowledge to get the audience dancing during Light Dreams. They can even learn to create their own 3-D computer animation.

“This event showcases local talent in a way that hasn’t been done before,” Simpson says. “There’s so much going on in Birmingham at the intersection of art and technology, and we want people to experience that firsthand.” The artists are enjoying the challenge—everyone participating in 2013 is back this year—and Bruno envisions the collaboration as the first step toward an ASC-centered artist community. In fact, she plans to build on the momentum by opening spaces in and around the ASC where local artists can create and practice their works.

“We have a passion for local artists,” Bruno says. “UAB can be a safe haven for them.”

Flipping the Switch

Last year, “everything ran past the time it was supposed to happen,” she recalls. “But artists helped other artists set up installations. The tech team and the ASC staff pitched in. I physically put together stages. It really is a team effort.”

Organizers have limited time to prepare the site for Light Dreams because they must work around the busy schedule of a university campus in the city center. The façade’s polyester screen and many of the art installations take their final shape a few hours before the event—but even the artists themselves don’t know how the pieces will look on location until the sun sets. “None of the works can test in the daytime,” Simpson says. “Things don’t come together until the audience sees them.”

When things did come together last year, Bruno wept as she watched. “I was so nervous, but then I became overwhelmed by how incredible it was and the audience’s reaction to it,” she says. “I’m always moved by the arts and their ability to affect us.”

The success of Light Dreams will inspire more innovative, original productions at the ASC, Bruno says. “UAB understands that art is the soul of a great city,” she says. “It’s what drives the creativity that helps us to pursue medical and technological breakthroughs and build a strong economy.” Light Dreams offers proof of that, she adds. When the plugs, pixels, and polyester align, “you will believe in the power of art in our community.”