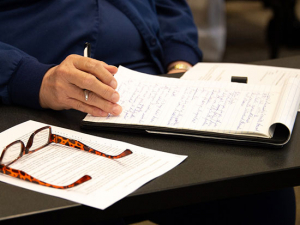

Nursing Professor and internationally recognized expert in forensic nursing and primary care Pat Speck, DNSc

Nursing Professor and internationally recognized expert in forensic nursing and primary care Pat Speck, DNSc

From UAB Athletics summer camps to researchers conducting youth-centric studies, many UAB faculty and staff frequently interact with minor children.

According to Pat Speck, DNSc, a nursing professor and internationally recognized expert in forensic nursing and primary care, everyone who interacts with children should be able to recognize signs of child abuse.

“The association of adult health and childhood trauma has more than 20 years of evidence,” Speck said. “The challenge for society is to ensure healthy beginnings through interventions with families in trouble who need resources to lessen the chance of long-term health issues with their children.”

Speck and eight other nursing faculty contributed their expertise in domestic abuse, public health, trauma and more to a publication titled “Child Abuse Quick Reference 3E: For Health Care, Social Service, and Law Enforcement Professionals” to better prepare professionals across multiple disciplines to respond to child abuse.

The text is a primer for professionals without experience in the field, such as medical practitioners, social workers, attorneys and law enforcement, who increasingly are required to provide real-time responses to child abuse.

Speck distilled the tips in the book into four tenets to guide UAB faculty and staff working with children.

1. Children respond to abuse in varied ways — and not all reactions are negative at face value.

For most children, abusers are their parents, siblings or extended family, Speck said, but sometimes can be from other social systems outside the family, such as schools, churches or sports clubs, Speck said.

Some children do not understand what they’re experiencing is abuse, so they’ll have difficulty reporting what happened to them and often learn to cope in unhealthy ways.

|

“Protection agencies and agencies providing support and intervention to families in chaos can prevent continued toxic stress. Most parents want help to ensure their children are safe and healthy.” |

A child’s reaction to abuse and neglect may vary, but usually include the core family’s strategy for facing stress. Some children adopt attention-seeking behaviors and act out by yelling, fighting or taunting others, Speck said. Other children take initiative to “fix” problems for their siblings or the vulnerable adults in their family, Speck said.

“This co-dependent caretaking results in pseudo-maturity and super-achievement in acceptable venues, such as in academics,” Speck said. “The effect is that no one questions the escape from the family chaos to study.”

A child’s negative behaviors at each stage of development are easier to identify, Speck said. These can include unreasonable anger toward themselves or others, self-loathing, extreme emotions and drug use to escape their pain, obvious or continuous sadness or forced isolation from peers who aren’t comfortable around the disruptive behavior.

2. A child may test you before fully trusting you can help them — and that can take time.

Some children will disclose certain abuses in convoluted ways, using language unfamiliar to the listener, Speck said. When understood, a direct report is usually an effort by the child to get a specific kind of abuse to stop — even if other kinds of abuse are happening concurrently.

The disclosure might be minimal, such as saying, “I don’t like that person and don’t want to go where they are.” Another subtle example is a child wearing shorts in the cold weather to show whip marks on their legs, yet explaining that they were a bad child and deserved the abuse.

|

Some children do not understand what they’re experiencing is abuse, so they’ll have difficulty reporting what happened to them and often learn to cope in unhealthy ways. |

“The child tests the water with a simple report before trusting the system to rescue them,” Speck said. Failure of the system to protect the child at the earliest disclosure could doom the child to mistrust the system and be subjected to continued abuse.

Adults closest to the child with the most opportunities to observe them over time are the likeliest to spot signs of abuse, Speck said. Developing rapport with the child and parent to provide a culture of safety builds trust and allows space for a child and parent to report troubles.

3. Remember that children may try to hide their abuse in varied ways.

An obvious example of this, Speck said, is when children wear long sleeves and pants in the summer heat to hide marks of abuse, and when confronted,

|

To report suspected child abuse, immediately call UAB Police at 205-934-3535. Read UAB's Protection of Children policy in its entirety. Visit uab.edu/childprotection for more information. |

minimize or deny what happened to them. When questioned, neglected children also will offer explanations to minimize their situation. For example, a child may say, “I’m not hungry,” when there is no food in the house or money to buy lunch at school.

4. Seek an interprofessional evaluation of the suspected abuse or neglect.

Adults who were abused as children often experience health issues directly related to the toxic environment to which they were exposed during their youth, Speck said.

“Protection agencies and agencies providing support and intervention to families in chaos can prevent continued toxic stress,” Speck said. “Most parents want help to ensure their children are safe and healthy.”