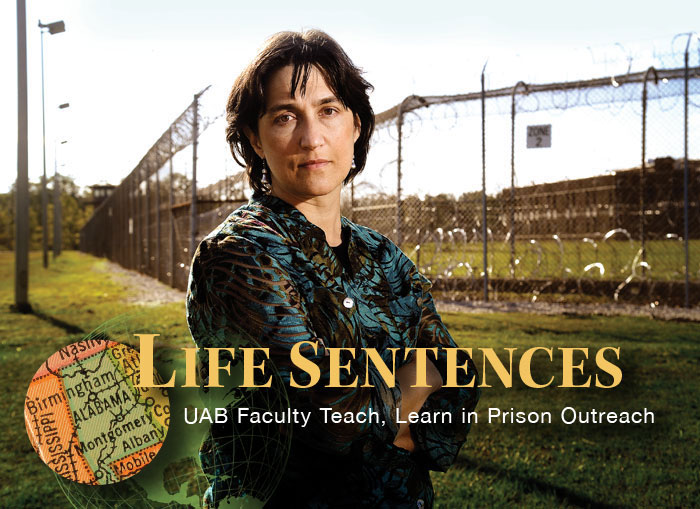

Each year, Alison Chapman (above) and other UAB faculty members take turns lecturing at Alabama’s Donaldson maximum-security prison.

Each year, Alison Chapman (above) and other UAB faculty members take turns lecturing at Alabama’s Donaldson maximum-security prison.

|

By Jo Lynn Orr By all accounts, the young man (we’ll call him Jimmy) was brilliant. He came highly recommended for admission to the UAB Honors Program. So it was a real shock for Ada Long, Ph.D., then director of the program, to awake one morning in 1987 and learn that Jimmy was under indictment for capital murder. “It was almost unbelievable,” she recalls. “He was an exceptional student and one of the smartest people I’ve known.” Jimmy was subsequently tried, convicted, and sentenced to life without parole. He was sent to West Jefferson (now Donaldson) prison to begin serving his term. “I visited Jimmy every week for a couple of years,” Long recalls. “I also became acquainted with many of the other prisoners at Donaldson and felt that it was a nightmare to be in such an environment with no intellectual stimulation.”

Changing of the GuardLong retired from UAB in 2004, but the Donaldson lecture series that she began continued, thanks to the advocacy of Ron Cavanaugh, Psy.D., who was then the prison psychologist and is now director of treatment for the Alabama Department of Corrections. In 2008, Alison Chapman, Ph.D., UAB associate professor of English, took charge of the series. “Typically, we send one or two faculty members a month to Donaldson to lecture on just about any academic subject,” says Chapman, who specializes in British literature of the English Renaissance period. “We’ve offered everything from acting workshops to lectures on Antarctic marine biology, German Expressionist art, and poetry.” Kathy Allen, Ph.D., a psychologist at the prison who coordinates the series with Chapman, says she is “delighted” with the contributions of UAB faculty members. “Our inmates just love it. I find that the UAB lecturers, especially if they’re coming out for the first time, almost always say things like, ‘I wish my freshman class was like this.’”

Chapman says she encourages faculty not to focus on coming up with lectures that they think will be appropriate for the audience. “Inmates usually want to learn about things completely outside their sphere of reference.” In 2005, after Chapman’s first lecture at Donaldson, she was asked to teach there on a regular basis. “Inmates wanted me to teach them about John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost,” she says. An essay Chapman wrote about that experience, “Milton’s Captive Audience,” was originally published in UAB’s PMS poemmemoirstory literary journal and was later listed in the “New and Notable” section of 2010’s Best American Essays. “They enjoyed Milton so much that they wanted to keep going,” Chapman says. “So the next year, we focused on Shakespeare’s King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, and Hamlet. Finally, the inmates said that the tragedies were too depressing—and could they please read some comedies. “They go right to the heart of really big questions about life and death, and all of the lousy things people do to one another,” Chapman says. Seeing the works through the inmates’ eyes has made “me quicker to reach for the deeper questions in the classroom,” she adds. The Iceman Cometh“Literature is sort of the crystal palace on the hill that can take inmates away from imprisonment for a while,” Chapman says. But the inmates at Donaldson have a chance to explore more than the world of books.

UAB polar biologists Charles Amsler, Ph.D., Margaret Amsler, and James McClintock, Ph.D., lead discussions at Donaldson on their research in Antarctica. It’s not unusual for them to have 30 to 40 inmates attend their talks. “We’ve had them help us demonstrate how to put on a dry suit, like the kind we wear when diving beneath the Antarctic ice shelf,” McClintock says. “This, of course, gets everyone rolling with laugher—watching some poor guy struggling to get into the suit.” It can be easy to forget the unique circumstances of students at Donaldson. “I recall one kid who looked about 16,” McClintock says. “He was so bright and attentive that I couldn’t help but ask the prison psychologist what he possibly could have done to land in a maximum-security prison. She replied, ‘Well, he killed his mother and father and his siblings with a hatchet.’ And I was stunned. I’m sure there are those who wonder why anyone would waste their time teaching people who are incarcerated. But that’s never been my feeling—and it wasn’t Ada’s.” Ducks in a RowThe alien nature of the prison can put people off at first, Chapman says. But, typically, once visiting lecturers begin talking, they find that they’re dealing with a very respectful, curious, and attentive audience. McClintock says he has received questions at Donaldson “that I would expect from students in a graduate seminar.” The inmates are also able to let down their defenses for a few hours. Dennis McLernon, M.F.A., UAB associate professor of theatre, first visited Donaldson in 2008. “I was looking for a unique way to volunteer,” he says. “The Donaldson experience provides that and more.” McLernon says he went in with no materials, “just an idea of starting acting exercises to create a sense of trust among all of us. To break down masks, I had everyone waddle and quack like a duck. They completely bought into the exercise and didn’t want to stop. We all quacked together in a circle. After I left that first night, I knew I had to keep doing this. I’ve been conducting workshops at the prison ever since.” Like many of his fellow visiting lecturers, McLernon credits the Donaldson experience with giving him a new perspective. “Suddenly the smallest freedom becomes absolutely spectacular,” he says. “It encourages me to meditate on all that I have and acknowledge gratitude for those things and the people in my life.” |