The Never-Ending Story

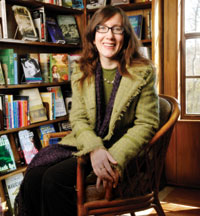

Kerry Madden, M.F.A., Assistant Professor of English • Novelist

By Jo Lynn Orr

|

Kerry Madden says she discovered a love of writing as a fourth-grader. |

The twists of Kerry Madden’s writing life wouldn’t be out of place in a novel. She has written several—and also published plays and poetry, scripts for soap operas, and a biography of Harper Lee. Her teaching career has been equally eclectic, including stints at several prestigious writing programs as well as workshops for teen moms in Los Angeles and foreign language learners outside Shanghai. Last fall, she joined UAB’s Department of English, where she teaches creative writing and is the editor of the UAB women’s literary magazine, Poemmemoirstory.

UAB Magazine: Writing is such a subjective process. How do you identify students with exceptional talent?

Madden: As with high-achieving students in any discipline, potential good writers take feedback really well. They follow the directions for writing a particular assignment, and then they rewrite. They also act as giving and generous critics to the other members of the workshop by taking the time to read others’ stories and give really good responses. You can tell that those students take writing seriously.

And there are those students whose voices really come through in their writing. I mean, whether they’ve worked for 30 years at the phone company and are coming back to school to fulfill a lifelong dream of becoming a writer, or they’re 22 years old and have read a ton of young adult fiction, there’s just a voice that comes through. What has really been exciting is to hear some of the creative nonfiction written by those who are older—who grew up in Birmingham during the civil rights years, or in the 1950s before the civil rights movement. There were some essays based on those experiences that were painful to hear. But one of the writers said to the class, “Don’t judge me by what happened, just judge me on the writing.”

UAB Magazine: When did you first know you were a writer?

Madden: In fourth grade, when my teacher told me, “You’re a good writer.” That was the first time a teacher had ever complimented my writing. I immediately went home and wrote a story called “The Five Cents.” I thought I was writing about the five senses—I’ve always been a horrible speller. But fourth grade was when it clicked—the idea that I could write a story.

UAB Magazine: When did you first begin teaching?

Madden: I started out teaching English as a Second Language [ESL] at Garfield Adult School in East Los Angeles, where the movie Stand and Deliver was filmed. Then I became involved in teaching writing to teen moms. I just loved those girls. They were 14, 15, and 16 years old, raising kids and being told by adults, “Don’t use your big dictionary words with us. Don’t get above yourself; stay in your place.” I ended up becoming really close to a couple of them, and we wrote a play together.

During the 1992 L.A. riots, when it seemed like the whole city was burning, I was teaching ESL students ranging in age from 20 to 70 years old. They wrote and performed plays about the events unfolding then—many of them were personally affected because of the neighborhoods they lived in. One of the plays was called “One Hot Date.” It was about a girl who wants to go out and play in the fires, while the city is burning. It was exciting to see these ESL students, who were mostly from El Salvador, Mexico, and Guatemala, write and perform these plays. We staged them in the cafeteria.

I also taught creative writing in Ningbo, China, which is south of Shanghai. My Chinese students wrote 12 plays and performed them in English. There wasn’t a theater with a proscenium, so we moved the desk, the big teacher’s platform, and used it as a stage.

So I’ve been writing and teaching since college. After my first novel, Offsides, came out, UCLA asked me to teach in their writers’ program. I also taught at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. It has been kind of piecemeal teaching, I guess—one gig here, a residency there. That’s why it has been really exciting to be at UAB, where I have a full semester to spend working with my students.

UAB Magazine: How do you help students develop an idea into a story?

Madden: We do a lot of workshopping. I don’t lecture a lot because the lecture comes out in the feedback to the stories. Because the fiction class was so large last fall, we did workshops twice a semester with the whole group, but then every other week students were divided into smaller workshop groups. That way, they knew they would have to read something to the group and get a response.

I do a lot of warm-ups, simple things like evoking the favorite food they ate as children—or the most disgusting thing and whether they were they forced to eat it or dared to eat it. I try to include a lot of messy warm-ups that will spark memories or ideas to feed their stories later on. I have them write from the point of view of the main character, or from a minor character that they might need to get to know more.

I also encourage them to read their work out loud. In the beginning, they read their work out loud almost every day because that’s where you catch things. So it’s a combination of reading stories and warm-up assignments aloud—writing “sparks” is what I call them. What was their first job like, and how did they get it? How did they feel, halfway through a shift? Who was a character that could change the routine for them in that job? That always sparks something. You usually get that first job around 15 or 16, and it’s usually pretty humiliating—you’re wearing a uniform or reek of Thousand Island dressing.

UAB Magazine: How do you help students find the elusive quality of “voice” in their writing?

Madden: In my classes, I give students an exercise where they’re required to sit in a cafe and listen—just eavesdrop and write down everything they hear. These observations go into idea notebooks that I have them keep. Also, I tell them to meander while writing. I encourage them to overwrite, because they can always go back and cut it—especially in creative nonfiction, a newly defined genre that’s different from the typical five-paragraph topic essay. In creative nonfiction, you should feel free to meander, to contradict yourself. Writers should not be afraid to show themselves in a bad light—to show contradiction or weakness or vulnerability.

In vulnerable situations, you evoke something readers can connect with. So that, too, is voice. But it also goes back to good writing: strong nouns and verbs, active voice, catches of dialogue. For instance, yesterday I spoke at a library in Selma, followed by a luncheon. One of the dishes served was a casserole, and the person seated next to me said, “I like a good crunch! I like a CRUNCH!” I’ve never heard someone say that. It stuck with me. Listening to storytellers like Kathryn Tucker Windham helps with finding voice, too, because you become a really good listener, which is part of it.

UAB Magazine: Finding a publisher can be a writer’s biggest challenge. What kind of advice do you give students?

Madden: In the children’s writing workshop that I teach, I suggest students join the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI). Finding an agent or a publisher requires networking. An editor pulled my book Gentle’s Holler from the slush pile at an SCBWI workshop. “Don’t give me your manuscript,” he told us. “I’m boarding a plane to New York soon, but if you write me and say you were here, I’ll read it.”

For my creative nonfiction workshop, I invited Joey Kennedy—a Pulitzer-Prize winning editorial page writer for the Birmingham News—to speak to the class. Students then submitted opinion pieces to the paper’s editorial page and two students, Donna Thomas and Doug Betton, had their work published for the first time in November. They were also paid for their articles. So that’s a way to get started.

I also direct students to a great listserv called Creative Writing Opportunities. It’s a Yahoo group site that’s constantly announcing contests and residencies. Also, the links from the Web site Poets & Writers are good. I do a lot of e-mail follow-up with students to keep them aware of the current trends in publishing, and to stress that it’s a long road. It isn’t some magical thing that happens overnight. Getting published is a combination of focus and dedication, and not taking “no” for an answer.

UAB Magazine: Who are some of your favorite Alabama writers?

Madden: Mary Ward Brown. I love her work. Her stories just kill me. I also love Wayne Greenhaw, the poet. Helen Norris Bell is another writer I like. I have an essay I wrote about the three of them called “Words on Fire.” When I was working on the Harper Lee biography and she declined to be interviewed, I knew I had to speak to some women of her generation. Brown and Bell are 10 years older than Harper Lee, but they were so interesting in themselves that I didn’t end up asking much about her. I felt compelled to write their stories—Alabama women in their 90s who are writing.

UAB Magazine: What sustains you—as a person and a writer?

Madden: I think teaching does. It’s that exchange between students and teachers, especially when I’m working with little kids. The idea of being an elementary school teacher horrifies me. But to go into a classroom for an hour and encourage young students to write their stories—it’s like Prozac. They’re feeding me.

Kerry Madden is the author of four novels: Offsides and the trilogy Gentle’s Holler, Louisiana’s Song, and Jessie’s Mountain. Her latest book, Harper Lee: Up Close, was named one of the “Best Young Adult Books of 2009” by Kirkus Reviews.