The path to a career in medicine and health care is unique for every person. For some, the first spark of interest occurred while they were answering the call for a different kind of service in the military. In advance of Veterans Day, UAB Medicine magazine talked with several military veterans at the UAB Heersink School of Medicine to learn how their time in the armed forces impacted their professional lives and their journeys to medicine. With a unique blend of experience, dedication, and compassion, they continue to make a profound impact on the lives of others, embodying the true spirit of sacrifice.

Building Military-Civilian Partnerships

In 1999, Jeffrey Kerby, M.D., Ph.D., left UAB to join the military. When he returned to UAB four years later, he brought the military with him.

A Missouri native, Kerby originally came to UAB after earning both his undergraduate and medical degrees from the University of Missouri at Kansas City. He earned a Ph.D. in Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics from UAB in 1997, then completed his surgical residency.

In order to further his medical training, Kerby joined the United States Air Force under the Health Professions Scholarship Program. In doing so, Kerby was continuing a family tradition. His father served in the Navy during the Korean War, and his older brother spent 23 years as an Air Force fighter pilot.

During his time in the Air Force, Kerby made the connections and learned the skills that eventually led to the formation of military training programs at UAB, including the Special Operations Surgical Team (SOST), a permanently stationed group of active-duty Air Force personnel who work at UAB’s Level 1 Trauma Center.

“Serving in the military was the most important time in my career as far as the people I met and the relationships I developed,” says Kerby, who currently serves as the Brigham Family Endowed Professor in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery and is the director of the Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. “It definitely led to the collaborations we’ve been able to establish with the Air Force at UAB.”

The connections started during Kerby’s time at Wilford Hall Medical Center, located on the grounds of San Antonio’s Lackland Air Force Base. The center contained a verified trauma program that also served the civilian population.

While there, Kerby began working with the head of the trauma program, Donald Jenkins, M.D., on the development of small, mobile surgical teams that could be utilized in combat situations. Each team consisted of a trauma surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, scrub tech, anesthetist, and emergency medicine physician.

“The idea was for these small teams to be able to go far forward into a conflict, set up an operating room in a shelter of opportunity—a shed or a tree with a canopy—and establish a mobile OR to provide stabilizing damage-control surgery for injured combatants close to the front lines,” Kerby says.

Two years of planning and training were suddenly put to the test following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 and the ensuing conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“You always want to avoid those circumstances,” says Kerby, who was deployed in 2002 in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. “But given the need at that time, we were glad we had developed the teams and gone through the training and were ready to utilize that resource for the soldiers who were putting themselves in harm’s way.”

Kerby was able expand upon that work once he returned to UAB in 2003 following his departure from the Air Force, where he achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel. First, in 2006, Kerby used his military connections to bring an Air Force Pararescue Jumper (PJ) training program to UAB.

“They do rescues for downed pilots and anybody who needs to be extricated from a situation. They also serve a tactical role for specialized missions” Kerby says. “They’re already highly trained combat medics, but they need to maintain their trauma life-saving skills. When the opportunity presented itself to develop that program at UAB, I jumped at the opportunity to support this military mission in my new civilian role.”

The program initially trained approximately 50 Air Force personnel each year, but Kerby says it has expanded significantly in recent years thanks in part to the efforts of Daniel Cox M.D. In addition to being chief of UAB’s Trauma Service and an associate professor in the Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Cox is a 13-year Air Force veteran who still serves in the Air Force Reserves.

Under the direction of what is now called the Special Operations Center for Medical Integration and Development (SOCMID), the program will eventually train 300 to 400 personnel each year. “It’s turned into a total-force operation for trauma training for these Air Force PJs,” Kerby says.

UAB’s success with the original 2006 PJ program led to the establishment of the SOST program in 2010. Under the program, active-duty Air Force surgeons are credentialled to work at UAB’s trauma center, where they often encounter injuries similar to the type they might see on the battlefield.

“We now have four SOST teams stationed here taking calls in our trauma units, but they’ll also deploy as a team wherever they’re needed around the world,” Kerby says. “Building this military-civilian partnership at UAB and seeing it flourish and grow has been one of the most rewarding aspects of my career.

“The great thing about doing this at UAB is the collaborative spirit that’s part of the culture here. When we first started talking about this military-civilian collaboration and how it would need multi-departmental assistance, everybody was fully supportive of the idea. I never had a leader say no. It was always, ‘How can we get to yes.’ That’s what’s so special about UAB.”

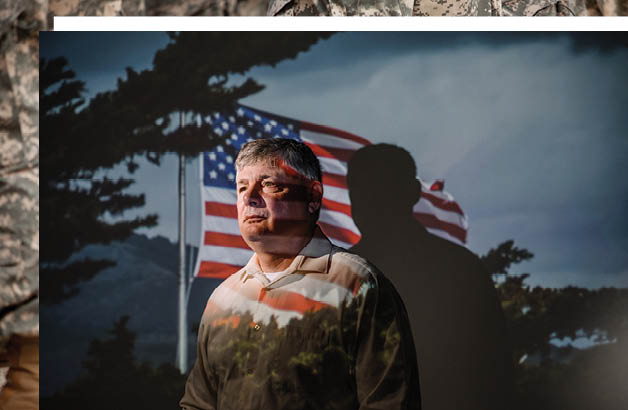

Rosylen Quinney's service with the Army Reserves Military Police in Iraq spurred her to consider a career in health care.

Rosylen Quinney's service with the Army Reserves Military Police in Iraq spurred her to consider a career in health care.

From Military to Maternity

After experiencing death up close as a young Army Reserves recruit, Rosylen Quinney decided she wanted to pursue a career dedicated to the creation and preservation of life. She currently is doing just that as a Clinical Research Coordinator II in the Heersink School of Medicine’s Center for Women’s Reproductive Health.

A native of Forkland, Alabama, Quinney graduated from Demopolis High School in 1987, then began a 10-year stint with the U.S. Army Reserves 1165th Military Police Unit. At the time, she envisioned that her military service would lead to a career in civilian law enforcement.

But in 1991, Quinney was deployed to Iraq for six months as part of Operation Desert Storm. While there, Quinney says she witnessed things “that a young woman from Greene County never could have imagined.” This included watching as one of the sergeants in her unit stepped on a landmine and died.

“It’s obviously something I will never forget,” Quinney says. “At first, I wanted to go into police work. But after being deployed and seeing all the death, I made up my mind while still there that I wanted to come home and be a nurse. That’s how my career changed from being a law officer to being in the medical field.”

It took more than two decades, but that decision eventually brought Quinney to UAB. She began her medical career in 1993 by working at a Birmingham senior-living facility and becoming a Certified Nursing Assistant. She then furthered her training through a program at Carraway Methodist Medical Center for Intensive Care Technicians.

In 2000, Quinney began working as a Clinical Medical Assistant with Alabama Neurology Associates, which is where she first became interested in the research side of the profession. That led to a series of roles as a Clinical Research Coordinator for several facilities, including the Birmingham Pain Center and St. Vincent’s Central Research Associates.

Quinney assisted on numerous clinical trials during that time, gaining experience in investigational drugs, medical devices, biologics, vaccines, surgical intervention, and other treatments and procedures.

Through it all, Quinney says she continually monitored potential job openings at UAB, where both her brother and sister-in-law previously worked. So when she received an offer in 2018 to join the Heersink School of Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in the Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, she jumped at the opportunity.

“I had never done OB/GYN or neonatal research, but as soon as I interviewed here, I knew this is where I should be,” Quinney says. “I just fell in love with the babies and the moms. Especially the babies.”

Quinney currently is co-coordinating the Randomized Trial of Continuous Airway Pressure for Sleep Apnea in Pregnancy study with the national Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network out of George Washington University. She serves as lead coordinator on the Identifying and Assessing Multi-Level Barriers to Equitable Postpartum Sterilization study and The Meaning of Screening Intervention Study which is evaluating the effectiveness of a prenatal screening educational game to improve knowledge and reduce decisional conflict among underrepresented and a range of health literacy levels of pregnant people.

Rosylen Quinney was awarded the National Defense Service Medal for her service in Iraq during Operation Desert Storm.

Rosylen Quinney was awarded the National Defense Service Medal for her service in Iraq during Operation Desert Storm.

But her primary passion is working as the program manager for the P3 Providing an Optimized and emPowered Pregnancy for You (P3OPPY) study, funded by the American Heart Association.

UAB is the coordinating center for the P3 EQUATE Network, which is a collaborative effort between research institutions and community

partners aimed at improving maternal and infant health outcomes. The study is being led by Rachel Sinkey, M.D., an assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Heersink School of Medicine, and Pediatrics professor Wally Carlo, M.D. The focus is on reducing health disparities among maternity patients, particularly for Black and underserved populations.

“We’re trying to see why African American women have the highest maternal mortality rate in the U.S., and why they have so many health disparities,” Quinney says. “I’m writing proposals, creating data files, facilitating meetings. I’ve learned how to do all that during the time I’ve been at UAB. I probably wouldn’t have the opportunity to be doing this if I wasn’t at UAB.”

Quinney says her years in the military taught her traits that she utilizes in her current role, including “how to be disciplined and pay attention to the smallest of details in order to execute my assignments.”

Of course, the smallest details that she enjoys the most are the babies who are benefiting from her research work. Welcoming newborns into the world is a long way—both figuratively and literally—from the Iraq experience that sent her down the medical path.

Challenges and Rewards

Most medical treatments and procedures are focused on curing the body, but for Pete Lane, D.O., his work is also about repairing the spirit.

Since 2004, Lane has been the medical director of Addiction Medicine in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology. In that role, he has witnessed the transformative power of successful addiction treatment.

“Nowhere in medicine that I’ve been have I seen a field where I can have such a huge impact on a person’s quality of life,” Lane says. “They transform physically, socially, and spiritually through the recovery process. If you take a photo of them when they get here and again when they depart, they don’t even look the same. Being able to watch somebody transform and grow into a sober person in recovery is hugely gratifying.”

A native of rural upstate New York, Lane became interested in medicine after enlisting in the Army in 1980. He says there was a shortage of medical lab technicians, so he volunteered and was sent to Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville for training.

“I became interested in the lab tests, where you’re looking at the biology of whatever problem the patient is going through,” Lane says. “I learned a lot about these tests, how to use them and what they mean. That got me interested in being able to diagnose a medical illness, which led me into wanting to go to medical school.”

Lane received his undergraduate degree in biology from the University of Alabama at Huntsville in 1988, graduated from Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine in Missouri in 1994, then completed a Family Medicine residency at UAB in 1997. He worked in private practice for a few years while serving as a volunteer faculty member at UAB before joining the Heersink School of Medicine full-time in 2001.

Over the past two decades, Lane has experienced the ups and downs of working in addiction treatment. Despite all the efforts to treat the disease, Lane says, “We’re still seeing a growing population that’s homeless and using substances.”

That is particularly true for military veterans. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, approximately 11 percent of vets who visit a VA facility for the first time are dealing with some sort of substance use disorder, a figure that is slightly higher than the general population.

“We need more people to get involved and to help treat this patient population,” Lane says, “as well as make changes above our level to hopefully eliminate this problem.”

But Lane also knows what is possible when a person suffering from addiction successfully experiences recovery. And that, he says, is what makes his role at UAB so rewarding.

“Sure, they’re not the most pleasant people to deal with at times, particularly when they’re intoxicated or in withdrawal. But once they’re sober, they’re just regular people,” Lane says. “There are some who you just can’t change. But for a lot of them, if you treat them appropriately and get them a safe discharge plan, then they’re not coming back.

“It’s really satisfying to see somebody totally change their life and be there for their family, go back to work, and be successful at life. That’s what I try to help them do.”

-Story by Cary Estes, Photography by Andrea Mabry

Celebrating 70 Years of Veterans’ Care

On March 16, 1953, the Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) opened its doors in the historic Southside district of Birmingham. Today, the medical center is a level 1A acute tertiary medical and surgical care center with 10 community-based outpatient clinics located in Anniston-Oxford, Bessemer, Childersburg, Guntersville, Gadsden, Huntsville, Jasper, Shoals, and two in Birmingham. The health care system employs more than 3,000 staff members that serve over 71,000 veterans in Alabama. On March 16, 2023, the Birmingham VA Health Care System celebrated 70 years of service with a special ceremony. The Heersink School of Medicine is the primary clinical affiliation and longtime partner of BVAHCS. Each year almost 700 Heersink School of Medicine residents rotate at BVAHCS, and over 115 medical students rotate at BVAHCS each academic year. In addition, research at the BVAHCS is conducted in collaboration with UAB scientists. Grants funded through the VA support numerous clinical and basic science research projects.– Emily Smallwood