UAB is celebrating 50 years of giving people like Rhonda Lusco a second chance at life through transplant medicine.Moving to a new city and changing schools is a difficult transition for any teenager, never mind a senior in high school. But in 2010, that’s exactly what happened to 18-year-old Megan Gagliardi when she and her family moved from Memphis, Tennessee, to Birmingham. She says starting at a school where she knew no one was hard. Therefore, when she began experiencing health issues, she ignored them because she was focused on making it through the school year.

UAB is celebrating 50 years of giving people like Rhonda Lusco a second chance at life through transplant medicine.Moving to a new city and changing schools is a difficult transition for any teenager, never mind a senior in high school. But in 2010, that’s exactly what happened to 18-year-old Megan Gagliardi when she and her family moved from Memphis, Tennessee, to Birmingham. She says starting at a school where she knew no one was hard. Therefore, when she began experiencing health issues, she ignored them because she was focused on making it through the school year.

“I would go to bed at night, and I felt like there was a pressure in my chest,” Gagliardi says. “I had this constant cough that never went away, but it was the end of the school year so I just tried to push through. After graduation, I told my mom how I felt. She took me to UAB where they ran a whole bunch of scans, test, and panels. They noticed there was a ton of fluid in my chest.”

Gagliardi’s UAB Emergency Medicine care team gave her a diuretic. “The next morning I woke up 15 pounds lighter,” Gagliardi says. “I had lost 15 pounds of fluid during the night.” After more tests, Gagliardi was diagnosed with a genetic form of dilated cardiomyopathy, which enlarges and weakens the heart muscle, preventing the heart from pumping blood efficiently.

Megan Gagliardi, pictured here with her mother Lynne Klinke, got the call that a heart transplant organ had been found on her 19th birthday. She calls the transplant “the best birthday present I’ll ever get.” Photo by Spindle Photography. Gagliardi’s unexpected diagnosis came with another frightening blow: She was in end-stage heart failure and would need a heart transplant to survive. “To get that news at 18, it just throws you into shock,” Gagliardi says. “But I knew I would have great doctors taking care of me.” She was put under the care of Salpy Pamboukian, M.D., and Jose Tallaj, M.D., both professors in the Division of Cardiovascular Disease, and James Kirklin, M.D., the James K. Kirklin Endowed Chair of Cardiothoracic Surgery in the Department of Surgery.

Megan Gagliardi, pictured here with her mother Lynne Klinke, got the call that a heart transplant organ had been found on her 19th birthday. She calls the transplant “the best birthday present I’ll ever get.” Photo by Spindle Photography. Gagliardi’s unexpected diagnosis came with another frightening blow: She was in end-stage heart failure and would need a heart transplant to survive. “To get that news at 18, it just throws you into shock,” Gagliardi says. “But I knew I would have great doctors taking care of me.” She was put under the care of Salpy Pamboukian, M.D., and Jose Tallaj, M.D., both professors in the Division of Cardiovascular Disease, and James Kirklin, M.D., the James K. Kirklin Endowed Chair of Cardiothoracic Surgery in the Department of Surgery.

Since the first heart transplant in the Southeast was performed at UAB in 1981, the UAB Heart Transplant Program has evolved into one of the most distinguished programs of its kind in the nation, with hundreds of heart transplants to its credit. Patients are cared for in a state-of-the-art, 23-bed Heart Transplant Intensive Care Unit, one of only a handful of its type in the country.

The day of her 19th birthday, Gagliardi got the news that a heart had been found. “I received my heart transplant on my 19th birthday, the best birthday present I’ll ever get,” Gagliardi says. “I just remember feeling so grateful. The night we went in for the transplant, my whole family was around me praying. I remember everyone crying, and at the same time I was thinking, ‘I’m so excited to be on the other side of this and to finally have my health back.’”

Gagliardi’s transplant was a success, and her doctors expect that her heart will last 15-25 years before she may need another transplant. She has since graduated from college, completed three half marathons, gotten engaged, and is co-writing a book with her mother about her transplant journey. “When I look in the mirror, my transplant scar represents to me my battle scar; it shows everyone what I’ve been through and what I’ve achieved,” she says. “After the transplant, people would give me advice like, ‘You can put oil on that’ or ‘You can use a scar cream and fade it away.’ I didn’t want to do that. I love my scar, and I love showing people what I’ve been through. It’s a huge part of me.”

Bringing Brighter Futures

Gagliardi’s transplant is one of more than 14,000 organ transplants UAB Medicine has completed since 1968, when Arnold Diethelm, M.D., performed the Medical Center’s first kidney transplant. Fifty years later, UAB performs heart, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, and bone marrow transplants, as well as multi-organ procedures. Led by Interim Executive Director Devin Eckhoff, M.D., and Co-Director Charles Hoopes, M.D., the UAB Comprehensive Transplant Institute has pioneered groundbreaking research, new therapies, and innovative techniques. It also helps UAB train the next generation of transplant leaders.

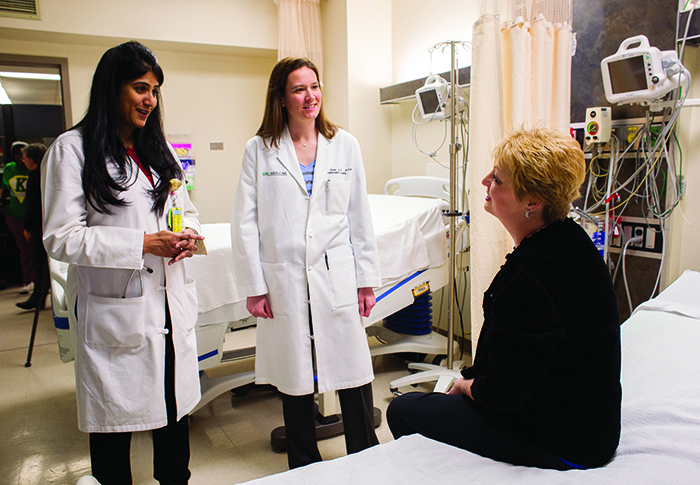

Left to right: Vineeta Kumar and Jayme Locke are using their roles with UAB’s Incompatible Kidney and Kidney Paired Donation Programs to alleviate the problems of donor incompatibility and the lack of available kidneys for transplant. Photo by Steve Wood.UAB’s kidney transplant program, one of the three largest in the country, has completed more living donor transplants than any other program in the U.S. since 1987. This past December, UAB reached the 10,000 kidney transplant milestone. The program is known for taking on complex cases that other transplant centers can’t manage thanks to a high level of expertise and the ability to combine multiple technologies to “push the envelope” to restore patients’ quality of life and save lives. In 2017 alone, under the leadership of Michael Hanaway, M.D., and Cliff Kew, M.D., kidney program surgical and medical directors, respectively, UAB completed almost 100 living kidney donor transplants at a time when the nation was seeing a decline in the number of living kidney donations.

Left to right: Vineeta Kumar and Jayme Locke are using their roles with UAB’s Incompatible Kidney and Kidney Paired Donation Programs to alleviate the problems of donor incompatibility and the lack of available kidneys for transplant. Photo by Steve Wood.UAB’s kidney transplant program, one of the three largest in the country, has completed more living donor transplants than any other program in the U.S. since 1987. This past December, UAB reached the 10,000 kidney transplant milestone. The program is known for taking on complex cases that other transplant centers can’t manage thanks to a high level of expertise and the ability to combine multiple technologies to “push the envelope” to restore patients’ quality of life and save lives. In 2017 alone, under the leadership of Michael Hanaway, M.D., and Cliff Kew, M.D., kidney program surgical and medical directors, respectively, UAB completed almost 100 living kidney donor transplants at a time when the nation was seeing a decline in the number of living kidney donations.

This bold attitude is reflected in the Incompatible Kidney Transplant Program, by which a living donor kidney can be transplanted into a patient despite the donor and recipient having different blood or tissue types, a problem in almost half of all living donor transplant cases. Many programs offer living donor kidney transplantation but require a fully compatible match. UAB offers desensitization pretreatment to overcome blood group and/or tissue incompatibility barriers. The program also collects incompatible donor-recipient pairs in a database and identifies connections among incompatible pairs to facilitate transplants.

UAB is one of three locations in the nation and the only one in the Southeast able to combine desensitization with paired donation at a single center, helping to meet a serious need in a state that ranks ninth in kidney disease. With roughly 2,500 people on the kidney transplant waiting list, Alabama has more people per capita in need of a kidney transplant than any other state in the nation. “Living donor transplants that result from combining kidney paired donation and desensitization programs now account for almost a third of all living kidney donor transplants at UAB,” says Vineeta Kumar, M.D., medical director of the Incompatible Kidney and Kidney Paired Donation Programs. “Growth seen through these programs is only possible because of the generosity of our many wonderful living kidney donors and their recipients.”

The UAB Kidney Chain is also tackling the problem of donor incompatibility. Through the Kidney Chain, a transplant candidate becomes eligible to receive a kidney if a family member or friend volunteers to donate a kidney to another patient. The chain began in December 2013 with Helena, Alabama, resident Paula King, who felt called to donate a kidney despite not having an intended recipient. King’s gift launched what is now the world’s longest kidney transplant chain, which reached 88 transplants this past December. Eighteen Kidney Chain donors are altruistic donors like King, but the program is full of stories of tremendous generosity.

“We’ve had compatible pairs who elected to receive from and give to a stranger instead of a direct donation so they could help others in need of transplant,” says Jayme Locke, M.D., surgical director of the Incompatible Kidney and Kidney Paired Donation Programs, and Kidney Chain coordinator. “That kind of sacrifice showcases a sense of community here that is very different from anything I have ever experienced in any of the places where I have previously worked. It’s one thing to give directly to your loved one; it’s something else to say, ‘I want to do more.’”

Setting Records

Inside the Donor Recovery Center at the Alabama Organ Center. Photo by Frank Couch.Advances like these plus long-running efforts by UAB transplant specialists to increase organ donation resulted in a significant increase in transplants at UAB in 2017, part of a national trend. UAB surgeons performed 462 total transplants in 2017—up from 398 in 2016—helping to fuel a national record of more than 10,000 deceased-donor transplants performed for the first time in a calendar year in the U.S.

Inside the Donor Recovery Center at the Alabama Organ Center. Photo by Frank Couch.Advances like these plus long-running efforts by UAB transplant specialists to increase organ donation resulted in a significant increase in transplants at UAB in 2017, part of a national trend. UAB surgeons performed 462 total transplants in 2017—up from 398 in 2016—helping to fuel a national record of more than 10,000 deceased-donor transplants performed for the first time in a calendar year in the U.S.

Deceased organ donor transplants at UAB rose from 318 in 2016 to 361 in 2017. Living kidney donors who donated through UAB’s Division of Transplantation also rose significantly, from 68 in 2016 to 96 in 2017. The number of organ donors within the state likewise has increased more than 53 percent over the past five years, while organs recovered for transplant have increased 55 percent.

The increase in deceased donations recovered for transplant is in part thanks to the growth of the Alabama Organ Center (AOC) housed at UAB, which opened a new Donor Recovery Center in February 2016. The AOC recovered and transplanted 495 organs in 2017, a record year for the organization. The Recovery Center is the second busiest in the nation and is the only in-house center of its type connected to an academic medical center the size of UAB. This attribute and the addition of critical care specialist Sam Windham, M.D., have helped improve donor management protocols at the Recovery Center, which has resulted in more organs utilized for transplant.

Traditionally, when an organ donor is declared brain dead, the process of maintaining the health of the donor’s vital organs until transplant surgeons can remove them occurs in the donor’s hospital. Recovered organs are then chilled and brought to the hospital where the transplant will occur. The amount of time that passes during transport can potentially diminish the quality of the organs.

As part of the new Recovery Center process, the AOC transports the donor to the Recovery Center with the donor family’s permission and at no cost to the family. The organ and tissue evaluation and recovery are then performed at the Recovery Center. Afterward, the donor is transported to the funeral home of the family’s choosing or to the state medical examiner for an autopsy if necessary. Bringing donors to the AOC Recovery Center significantly decreases the time from procurement to transplant, improving transplant outcomes.

Eckhoff says the increase in living donors in 2017 can be tied to the successful implementation of a Living Donor Navigator Program. As part of the program, each patient identifies a “living donor champion” to oversee his or her search for a compatible kidney. UAB surgeons performed six kidney transplants within the first six months the program was implemented in 2017. These donors were directly attributed to the advocacy role played by living donor champions.

Left to right: Devin Eckhoff and Charles Hoopes are co-directors of the UAB Comprehensive Transplant Institute. Photo by Nik Layman.Living donor navigators are trained UAB Medicine employees who help potential donors navigate the living donor evaluation process by answering questions, assisting them with completing required paperwork, setting medical appointments, and ensuring that donors have the support needed after surgery. In addition, the navigators are responsible for training and assisting the living donor champions, providing them with educational materials and other resources designed to help them be more comfortable with initiating conversations, and spreading awareness about living kidney donation. The program is modeled after a highly successful patient navigator program developed by the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Left to right: Devin Eckhoff and Charles Hoopes are co-directors of the UAB Comprehensive Transplant Institute. Photo by Nik Layman.Living donor navigators are trained UAB Medicine employees who help potential donors navigate the living donor evaluation process by answering questions, assisting them with completing required paperwork, setting medical appointments, and ensuring that donors have the support needed after surgery. In addition, the navigators are responsible for training and assisting the living donor champions, providing them with educational materials and other resources designed to help them be more comfortable with initiating conversations, and spreading awareness about living kidney donation. The program is modeled after a highly successful patient navigator program developed by the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“The goal is to improve the chances of locating a donor, given that some patients may be too sick, too busy with treatment and other responsibilities, or too withdrawn from social circles to effectively manage the search,” Eckhoff says. “In some cases, the patient simply may not want to ask others to donate such a priceless gift. Choosing a living donor champion helps eliminate the need for patients to serve as their own advocates.”

Looking Ahead

When discussing Alabama’s heavy burden of kidney disease and the limited supply of available organs during his annual State of the School of Medicine Address this past January, Selwyn Vickers, M.D., FACS, dean and senior vice president for medicine, did not mince words: “We will never have enough human organs to solve this problem.” Approximately 22 people die each day waiting for a transplant in the U.S.

The School of Medicine is pursuing a cutting-edge solution to the lack of transplant organs thanks to multimillion-dollar grant received in 2016 from biotechnology company United Therapeutics Corp. to launch a pioneering Xenotransplantation Program. The program is aimed at generating kidney transplants from genetically modified pigs to humans by 2021. Two of the country’s foremost xenotransplant researchers, Joseph Tector, M.D., Ph.D., and David Cooper, M.D., Ph.D., joined UAB in 2016 to lead the program.

“Drs. Cooper and Tector are asking the hard biological questions—not just can you take an organ from a pig, but can you genetically engineer the pig to protect its kidneys from the human immune response?,” Vickers said during his address. “It’s the vision of the Department of Surgery and the school to be the first in the world to transplant a pig kidney in a human. This is another example of how we as an institution can have local, national, and global significance.”

Xenotransplantation is not entirely novel. Pig heart valves have been used for years without ill effect and are generally rejected only very slowly. UAB scientists believe whole organ transplants from genetically modified pigs are possible in the near future if immunological and physiological barriers can be overcome. The first step is kidneys, but possibilities also exist in pig islet transplantation in patients with diabetes; neuronal cell transplants for patients with certain neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s; corneal transplantation; and eventually in providing pig red blood cells for transfusion into humans, particularly in areas where the availability of human blood is limited.

“We want UAB to be the premier center for end-stage organ disease, whether it’s liver, heart, or kidney. There is no doubt that our list of those awaiting transplants—especially kidney transplants—is steep, and the cost of ongoing dialysis care is prohibitive,” Eckhoff says. “Even if you had 100 percent consent from every brain-dead donor in America, you still wouldn’t have enough organs to fill the need. And here in the South, we’re in the hotbed of organ failure—kidney failure, liver failure. People are dying waiting for organs. Xenotransplantation is a natural fit for us as a university and may spur many more biomedical opportunities in our region.”

To learn more about giving to UAB’s transplant programs, contact Christian Smith at 205-934-1974 or cnsmith@uab.edu. To learn about becoming a kidney donor, call 888-822-7892 or visit UAB Medicine's living donor website.

By Tyler Greer and Jane Longshore