While popular culture likes to brand science as logical, objective, and serious and art as more emotional and subjective, the two fields are “oddly parallel,” says Doug Baulos, M.F.A., assistant professor in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences Department of Art and Art History. “At its foundation, art is about perception and experience, and that’s basically what science is as well.”

This spring, Baulos helped students bridge the divide in a course focusing on scientific illustration—a broad field encompassing everything from diagrams and infographics to medical illustrations for academic texts to digital 3-D model-making. Science needs art to help communicate concepts that can’t be explained easily or succinctly in words, Baulos says. In his own early days as an illustrator, Baulos worked for a plastic surgeon and gave patients a preview of their new look after a procedure. “They need an artist for that,” he says. “Art graduates have a ton of opportunities for careers in science.”

In turn, science gives art the tools for creativity—it takes chemists to create paints and other art supplies, after all. But just as important, science “supports art by giving it a basis and structure,” says Anna Zoladz, a senior art major who took Baulos’s class. “Research strengthens our artwork and gives it meaning; we know what we’re doing and why we’re doing it.”

An illustration created for the class by art student Katelyn Ledford

An illustration created for the class by art student Katelyn Ledford

You know a class is going to be good when it begins with a lesson in alchemy. The ancient tradition, which blended chemistry, philosophy, symbols, myth, and magic in an effort to transform materials or people, helped birth modern science and art, Baulos says. But the two fields have crossed paths countless times throughout the millennia, beginning with prehistoric humans who used cave drawings to record their world—and to attempt to understand the invisible forces that controlled it.

Baulos took his students from the Renaissance, where Leonardo Da Vinci tried to integrate scientific logic with artistic inspiration, through the early 20th century, when both Einstein and Picasso revealed radical new ways to look at the universe, and into today’s digital world, where the real and virtual merge. Students also visited UAB’s Reynolds-Finley Historical Library, where librarian Peggy Balch introduced them to rare illustrated manuscripts, some dating back to 16th-century Europe.

There, junior art major Vincent Rizzo became fascinated with the hand-drawn, hand-colored images depicting the latest knowledge about medicine and science in the Middle Ages. (One image in particular, known as “Wound Man,” shows battle injuries—with arrows, swords, clubs, and the like actually embedded in a man’s body—that medieval caregivers might treat.) “I’ve also been studying books about ghosts and apparitions,” says Rizzo, a Birmingham native who took the class to refine his illustration skills. The easy availability of that kind of history “has given me a different perspective,” he explains. “I’ve gone from drawing simple comics to creating silkscreen prints inspired by designs from the library’s books.”

Back in the 21st century, Baulos helped his students understand the secret to creating a successful scientific illustration: refining an idea so that it communicates to an audience at a broad level. He also taught them how to get jobs so that they can apply that knowledge. “Illustrators must know how to document things, how to present to a client, how to get paid, how to get an agent, and so forth,” Baulos says. “This is not a drawing or painting class; it’s specifically about the professional disposition of being an illustrator.”

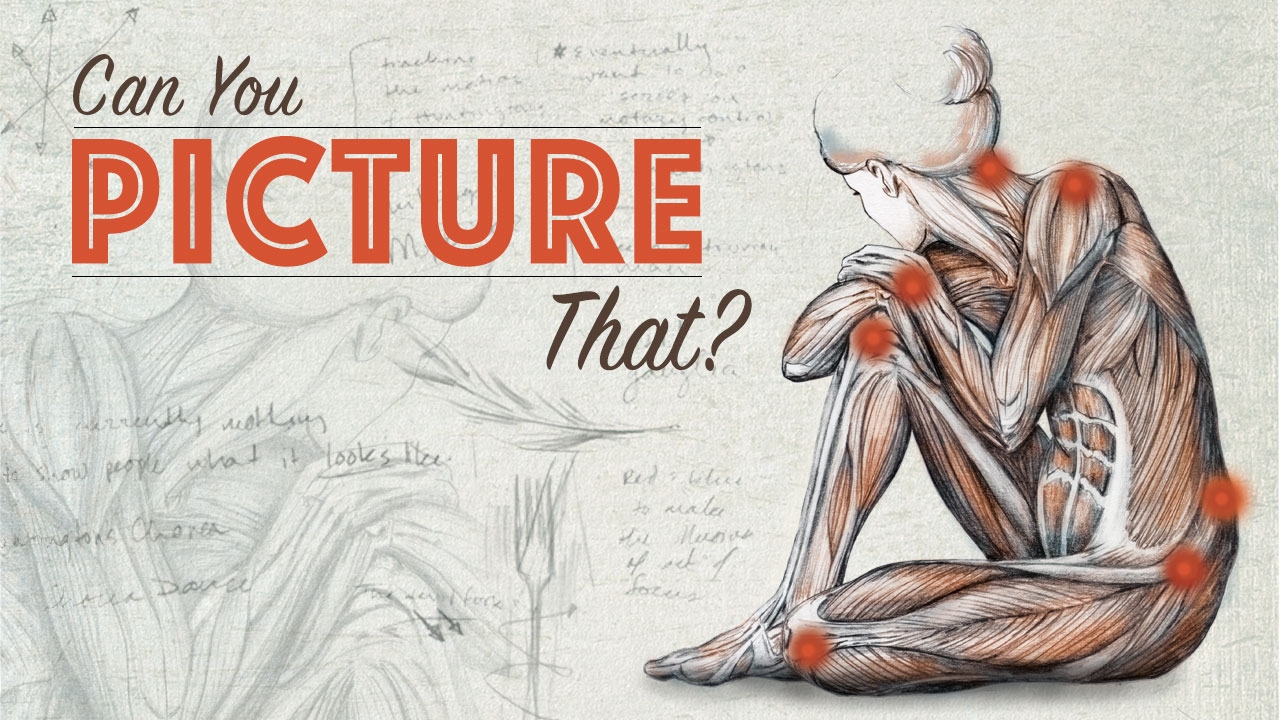

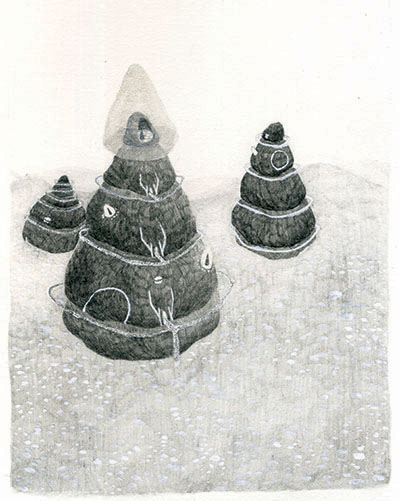

Annabelle DeCamillis's illustration offers a glimpse into a life with fibromyalgia.

Annabelle DeCamillis's illustration offers a glimpse into a life with fibromyalgia.Each of the 24 students chose a scientific field to research—some went with advanced physics, math, and even animal husbandry. Senior Hannah Rettig, who creates intricate pencil drawings of bones, focused on anatomy to hone her artistic skills. Another student embarked on a quest to depict math equations in three dimensions. The students then brought their findings to life through a series of projects leading to a portfolio of publishable illustrations. “We focus on design, typography, ornament, the historical portrait—the types of illustrations that clients ask for over and over,” Baulos says.

Some of UAB’s renowned scientists, including Jacqueline Nikles, Ph.D., associate professor of chemistry, and Jarred Younger, associate professor of psychology and director of UAB’s Neuroinflammation, Pain, and Fatigue Lab, also spoke to the class. Younger’s research into the potential causes of fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, and his strides toward future treatments, inspired an assignment to illustrate the experience of living with those conditions. Some of the resulting images now hang in Younger’s lab, where they can provoke discussions among scientists and patients. (See Rettig's fibromyalgia image at the top of this page; DeCamillis's illustration is at right. UAB Magazine featured Zoladz's work from this assignment in a story about fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue.)

“I was proud of my class for understanding that fibromyalgia is a spiritual disease as well as a physical one,” says Rettig, an art major from Bessemer, Ala. “This course has given us the vocabulary and references to articulate that science and art are interconnected.”

The interdisciplinary approach to teaching and learning sets an example for students to follow, Baulos says. “It’s important for their perspectives to be broad,” he explains. “Clients will ask them to illustrate things they don’t know anything about, so they have to be good at networking with people in other fields.”

An illustration created for the class by Anna Zoladz

An illustration created for the class by Anna Zoladz

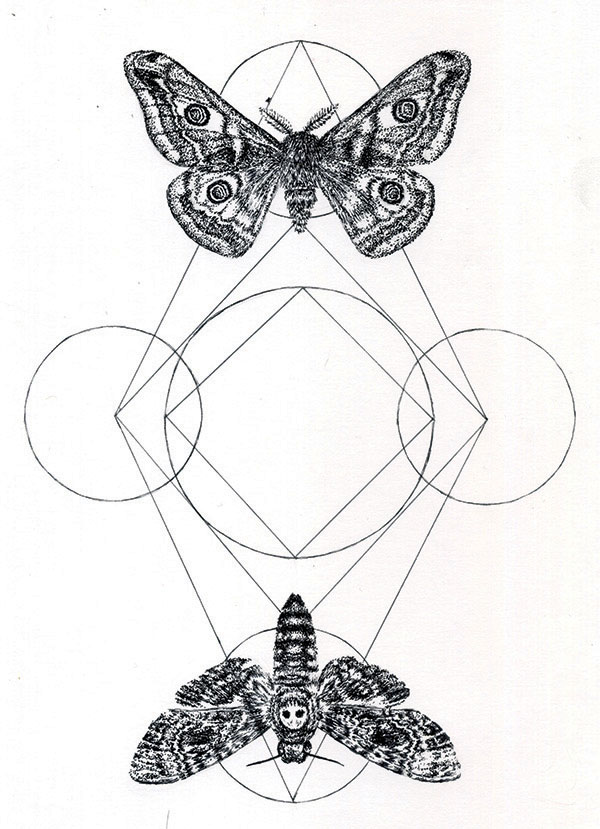

The course took the students into artistic territory beyond their comfort zones. Baulos encouraged Zoladz to depart from drawing and painting and experiment with creating sculptures for the first time. She made “a terrarium—an encapsulated landscape,” says the Huntsville, Ala., native. Lessons on scientific research helped Annabelle DeCamillis, a sophomore art major from Birmingham, further her explorations in the medium of costume design.

“You need a form of the scientific method to figure out your personal aesthetic,” explains DeCamillis, who also is a painter. “All art is much stronger when you have research behind it—when you’re informed about your subject.” Now, she says, she knows how to research historical costumes to find inspiration for her original designs. She also is applying her newfound knowledge to illustrate a new book authored by James McClintock, Ph.D., UAB’s Endowed University Professor in Polar or Marine Biology and a renowned Antarctica researcher.

“Some things can’t be explained in words,” says Zoladz. “Visual imagery can solve a lot of problems.”

Zoladz started school as a neuroscience major before switching to art—but what’s surprising is that her situation isn’t surprising at all, Baulos says. “A lot of UAB science students take art classes, and we have a ton of art students who are interested in various aspects of science,” he explains. “Some of our best students have double-majored in art and science. That does not happen at every university.”

“Everything I did in science is inherent to what I do in art,” Zoladz says. “I’m still interested in a lot of biological processes, and my drawings, like my scientific work, are really technical.”

Baulos has long nurtured his own fascination with science and medicine, which influences his drawing, sculpture, mixed media work, and other creations. “In my book arts work, I’ve researched the last thousand years of suture sewing and incorporated those stitching techniques into bindings,” he says. “I’ve tried to stretch the possibilities of how pages can be put together.”

An illustration created for the class by Annabelle DeCamillis

An illustration created for the class by Annabelle DeCamillis

• Learn more about the classes and degrees offered in the UAB Department of Art and Art History.

• Give something and change everything for UAB art students by supporting scholarships.