“You did financial projections for one month. What about 12 months?”

“Where’s the logo of the organization? Where is your team name on this?”

“Why did you pick Manhattan for your comparison city to Birmingham?”

The UAB Collat School of Business students on the receiving end of these questions sat silently, some taking notes, some with eyes wide open.

“That spreadsheet on the PowerPoint was overwhelming. We couldn’t follow it.”

“Did you interview people at the organization?”

The students, divided into three teams, had just outlined their strategies for a panel of business leaders from UAB and the community. Each team had 15 minutes to discuss its initial research and offer recommendations on the feasibility of two proposals. It was just like any business presentation. Except that the business in question is a nonprofit organization, and the presentation is part of a semester-length service-learning project at the heart of UAB’s Nonprofit Management course. Instructor Annetta Dolowitz has designed both the project and course to show her students what life is like at the reins of a nonprofit organization.

Doing Good, Facing Challenges

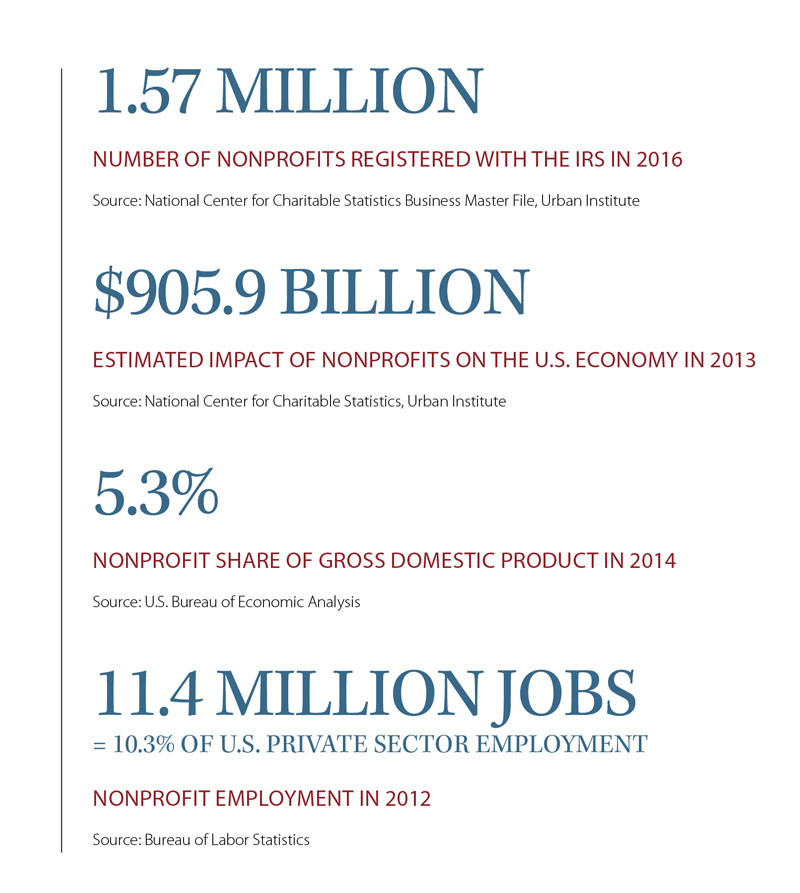

Many people misunderstand nonprofit organizations, thinking that they “are not responsible for what happens financially or strategically; they are just out there doing good in the world,” says Betzy Lynch, executive director of Birmingham’s Levite Jewish Community Center (LJCC). “But while we are there doing good in the world, we also are a business just like everyone else,” facing the same challenges, whether it’s revenue, personnel, or market share.

At the beginning of the semester, Lynch came to the class to talk about the LJCC, a family-oriented recreational and educational facility on 70 wooded acres off Montclair Road. The organization had two needs to assess: Could it increase rental of its facilities? Was it viable to expand after-school offerings? The students voted to take those on as their class service-learning project. Lynch would provide data and answer questions. “We asked them to look at programming that already exists and make some strategic improvements,” says Lynch, who knew Dolowitz from speaking to her classes about using a SWOT (strengths/weaknesses/opportunities/threats) analysis in a nonprofit setting. Last year Dolowitz asked if the LJCC had any research needs. Lynch jumped at the chance, and she likes that she got the opportunity “to see the LJCC through completely objective eyes.”

Layering Information

Suited up and sounding professional from the start, it was clear from their presentations that all three student teams had done some homework:

“The threats may be a saturated market. Our SWOT analysis shows a high level of start-up costs while the growth rate for this market is less than 1 percent.”

“You have the opportunity to market your facilities to leagues or intramurals.”

The students received praise for their professional approach and initial research. Dolowitz complimented them for being the best prepared class in the course’s history. But senior Lalit Karnam called it “pretty nerve-wracking.”

“I made it clear to the kids they are guinea pigs,” says Dolowitz of her methods to prepare students for the real world before they get there. “The panel helps them understand the professionalism that is required.” She describes the course as a layering of information, much of it provided by a network of local nonprofit and for-profit leaders who speak to her classes.

“One would talk about finance, and somebody else about boards [of directors], project planning, or timelines,” says Kwesi Butler, a business management major from Birmingham. Two guest speakers came each week, each one explaining what students should know about his or her area of expertise. Afterward, Dolowitz and the students discussed what was presented.

Those insights “helped us put together our whole presentation, with budget, SWOT analysis, timeline, and so forth,” Butler adds. “It all came together right at the end.” With its due dates and schedules, the class felt like a real job, he says.

Each student completed an individual project while contributing to the LJCC research and presentation. Dothan, Alabama, native Anna Buie, who graduated in human resource management in April, created documentation to support Leeds-based The Red Barn, which uses horses to help connect to people with disabilities. It was among half a dozen nonprofits Dolowitz had lined up to benefit from the class.

“I have never had a class that has been this demanding, but I also have never had a professor who worked this hard,” Buie says. “She is trying to get us as much experience as possible. It has given me an inside look at what a nonprofit organization is like.”

(Left to right) LJCC director Betzy Lynch meets with students Kwesi Butler, Lalit Karnam, and Grant Walkup to discuss their plan to enhance the nonprofit’s programs.

(Left to right) LJCC director Betzy Lynch meets with students Kwesi Butler, Lalit Karnam, and Grant Walkup to discuss their plan to enhance the nonprofit’s programs.

Practical Application

For Dolowitz, the key is a “flipped classroom” approach. “You need to study, you need to figure it out, and have this stuff ready to apply when you get to class,” Dolowitz tells students. “I care more about if you know how to apply the information you get, rather than if you can parrot it back to me.”

Karnam, a native of India majoring in health care management, calls it his most interactive class at UAB. “I thought this class would be like any other—take tests, write a paper or two. Actually, it is exactly the opposite.”

Grant Walkup, a marketing major from Columbiana, Alabama, says that students understood the end point; it was up to them to figure out how to get there. “There was a ton of material, but we had to go out and get it ourselves,” he says. They also handled challenges along the way; for example, they used Google Hangout to connect remotely with a class member who traveled for work and couldn’t attend group meetings.

The three teams returned to the panel for their final exam—this time for poster presentations. They all have bragging rights on their resumes for creating the LJCC proposal, Dolowitz says. As for Lynch, she is sharing the students’ final report with her staff, and she expects them to make good use of the recommendations. She credits the course with giving students comprehensive, practical knowledge that is applicable in both nonprofit and for-profit settings.

Several of the students say that the course has encouraged them to look at careers in the nonprofit world. “It has opened my eyes and broadened my horizons,” Butler says. “In this class, we weren’t just taking tests; we were making a difference in the community.”