Alumnus Boosts Nation’s Drug Defenses

By Matt Windsor

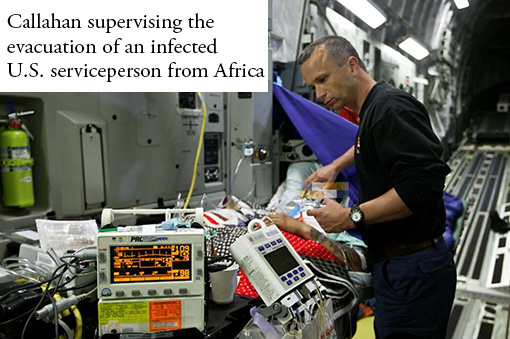

Michael Callahan, an alumnus of the UAB schools of Medicine and Public Health, has pioneered revolutionary methods of producing vaccines and predicting and reacting to virus outbreaks. Photo: Joseph Ferraro, Massachusetts General Hospital

Michael Callahan, an alumnus of the UAB schools of Medicine and Public Health, has pioneered revolutionary methods of producing vaccines and predicting and reacting to virus outbreaks. Photo: Joseph Ferraro, Massachusetts General Hospital

If there is trouble somewhere in the world, Michael V. Callahan, M.D., DTM&H, M.S.P.H., probably isn’t far away. For three months every year, Callahan, a 1991 graduate of the UAB School of Public Health and 1995 graduate of the UAB School of Medicine, works in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital. The rest of his time is spent on the move.

Callahan has been on the scene at some of the world’s most famous—and dangerous—virus outbreaks, including H5N1 avian flu in Hong Kong in 1999 and 2001, SARS in Hong Kong in 2003, Marburg in Angola in 2004, and so on. He also has responded to recent Ebola virus outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lassa fever in Nigeria, and controversial laboratory accidents resulting in the infection of scientists at foreign biohazard laboratories.

But Callahan’s most enduring contribution to health care may come from the lab rather than the field. Since 2005, he has been a program manager for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the secretive R&D center of the American military. Callahan was recruited to DARPA “to work on fast-paced solutions to health threats,” he says. His biggest mission: Create a government-funded drug research and production capability focused strictly on national priorities, such as defense and pandemic preparedness, rather than profits. “The Department of Defense had no idea how to make drugs, and neither did I,” Callahan recalls. But they knew they needed to learn how.

Rush Request

“The military is most concerned about the diseases of the tropics and the diseases of bioterrorism, but these are rare globally,” Callahan says. “Even though you might have 170,000 deaths per year from yellow fever, that’s not going to be a money maker for a drug company, so they aren’t interested.”

Big Pharma itself is undergoing seismic shifts. Many formerly U.S.-based firms are transferring their operations to countries such as China, India, and Brazil as the industry pursues expanding markets and takes advantage of lower overseas research costs. It is in America’s interest to make sure that cutting-edge work is supported at home, Callahan explains.

His solution mirrors the evolution of the modern military. Instead of amassing a standing army of researchers, Callahan opted for a special forces approach. His team identified promising work in U.S. labs, offering researchers the funding and equipment they needed to turn their discoveries into patient-ready treatments directly as “distributed manufacturing centers.” In 28 months, DARPA-funded projects created six new vaccines, leveraging taxpayer dollars into economic payback at a ratio of up to 11:1. “It’s been wildly successful,” Callahan says.

Callahan also thought carefully about his targets. He developed a strategy called “twinning,” in which he would search for treatment approaches that could be applied to related diseases: one of interest to the military or government (such as bird flu, with its potential to cause a pandemic), and the other attractive to drug companies and venture capitalists (the regular flu). These players could then help fund development costs needed to bring the products to market.

(Story continues beneath the photo)

Out with the Eggs

One of Callahan’s major goals was to find a way to replace the traditional egg-based methods of producing vaccines, which can take “eight years to forever” to develop, and six months or more to actually produce. His team launched a project called Accelerated Manufacturing of Pharmaceuticals (AMP), which has found a solution in tobacco plants. Grown in “bug-free hydroponic facilities,” the plants can be easily and rapidly altered to express the needed vaccine products in a matter of weeks. “One 2,000-square-foot chamber consisting of 12 robotically controlled trays can produce up to three million doses of flu vaccine” in a month’s time, Callahan says. The factories are portable, allowing developed countries to quickly acquire domestic vaccine manufacturing capabilities. These factories can be remotely guided and operated by teams back in the United States or elsewhere.

Meanwhile, a program known as Prophecy seeks to predict emerging virus threats and develop vaccines or other treatments before they hit. Working in small teams with foreign governments, DARPA has established an early warning system that can rapidly collect and share information across borders. In March 2009, the Prophecy network was the first to detect sick flu patients in a Mexico City intensive care unit, an indicator of the coming 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

“In a perfect world, doctors in Indonesia would see a new virus, sequence it, and send us the information by e-mail, turning genetic information into digital information,” Callahan says. Within a matter of days, Callahan’s team can identify the virus and its mechanism of action, letting health workers know if there is an existing vaccine that will help. If not, Callahan says, “we can create a new one, and produce between 30 and 160 million doses of a vaccine within a month.”

Path to Birmingham

Callahan’s interest in combining medicine and travel started early. The Boston native put himself through college at the University of Massachusetts and graduate school at UAB by working as a paramedic. He started traveling overseas on relief missions in the early 1980s; in 1988, he founded a charter organization that provided emergency medical evacuation and refugee medical care in developing countries.

Faster, Higher, FartherAs if reinventing the drug industry is not enough of a challenge, Michael Callahan is also using a “twinning” approach to revolutionize high-altitude acclimatization for mountain climbing. The lifelong mountain climber (he has worked with California’s Yosemite Search and Rescue team since the late 1980s and made regular trips to climb in Steele, Alabama, when he was in medical school) is testing a method to rapidly acclimatize mountaineers to high-altitude conditions. A therapy using an inhalable gas—similar to an albuterol inhaler for asthma, Callahan says—is currently in phase 2 clinical trials, including a planned study on Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro. The military implications are obvious. “Our soldiers in Afghanistan have to chase bad guys uphill at anywhere from 14,000 to 18,000 feet,” Callahan says. “At the moment, it takes 24 to 46 days to truly acclimatize to those conditions, especially since most of our troops are coming from bases in the United States that are at or near sea level.” But the civilian uses are even wider, Callahan explains. The same treatment “could also treat pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic hypoxia from lung disease,” which affect millions of patients worldwide. |

He determined to pursue a career in infectious diseases, and was initially attracted to UAB by the well-regarded Master of Public Health program in international health at the School of Public Health. “I came to UAB at a time of explosive research growth in the late 1980s, during the heyday of the HIV epidemic,” Callahan says. After graduation, Callahan worked in a research lab at Tufts University for a few years before returning to Birmingham to attend the UAB School of Medicine. In 1996, he was awarded the Tinsley Harrison Scholarship for his work in infectious diseases.

“The medical school is in a really great position, placed in the heart of the state’s main population center, but with rural training opportunities close by,” Callahan says. “I had great training, especially on the clinical wards.” Callahan continues to work with colleagues at UAB, he says, including David Freedman, M.D., in the UAB Division of Infectious Diseases, and several members of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine.

Forward Thinking

The challenge of running DARPA programs for seven years has been thrilling, but Callahan says he is ready for new adventures. In fall 2012, he returned to Massachusetts General Hospital to establish a global disease prediction program funded by the Department of Defense and to conduct clinical antiviral drug trials in Africa and Asia. He hasn’t relinquished his frequent-flyer status, however. “I still have federal responsibilities to the Department of Defense and the White House for pandemic preparedness and exotic disease outbreaks, which will continue for the near future,” he says.

Meanwhile, Callahan is excited to see how the techniques he funded at DARPA can be adapted to inefficient bureaucracies everywhere. The White House and the National Institutes of Health are both very interested in the model, which could have applications that reach far beyond infectious diseases, Callahan says. “The technology is cool,” he says, “but this experimental business strategy they allowed me to try will have implications across government."