I have been doing a lot of diving lately. Most of my underwater excursions (6 in the last 4 days!) have included videotaping the lovely communities living on the seafloor in the waters around the station. Much of what we see is permanently attached to large rocks so we cannot collect them to live temporarily in the station’s sorting table. For today’s episode of All Creatures I will use scene grabs from the videos to introduce you to creatures that are fixed in place. Read on to ‘be at home’ with these homebody critters.

In places on the seafloor not covered with stands of brown algae, we can find a diverse and colorful array of invertebrates. Among the more obvious are sponges. Sponges are very simple, multicellular organisms in the Phylum Porifera – a Latin name for porous. Their body is covered by pores through which they get food, breath, and excrete. All pretty amazing. Those pores also make some of them capable of absorbing a lot of water – hence the kitchen sponge. Good news for the phylum is that now most kitchens use manmade sponges.

Sponges come in various shapes, sizes and colors. The opening image shows multiple strands of stringy green algae and numerous small red algae but also two different sponges. In the lower right and upper left corners are yellowish, round sponges each about the size of a softball, which is our common name for it. In contrast, the bright red-orange band above the lower softball sponge is different species. Crella is an encrusting sponge, growing only a couple of millimeters thick but can cover a dinner plate size area. Several years ago Team UAB determined that this sponge produces a potent chemical to prevent animals from eating it. Many attached organisms, especially in Antarctica, defend themselves using chemical warfare. Crella’s defensive chemical, or natural product, was isolated and purified by our chemist colleagues and christened norselic acid. Lab trials have shown that synthetic norselic acid has promise as an antibiotic. (By the way, the numbers in the lower right of the image indicate the image depth 32.8m (108 ft) and water temperature 2oC (36oF).)

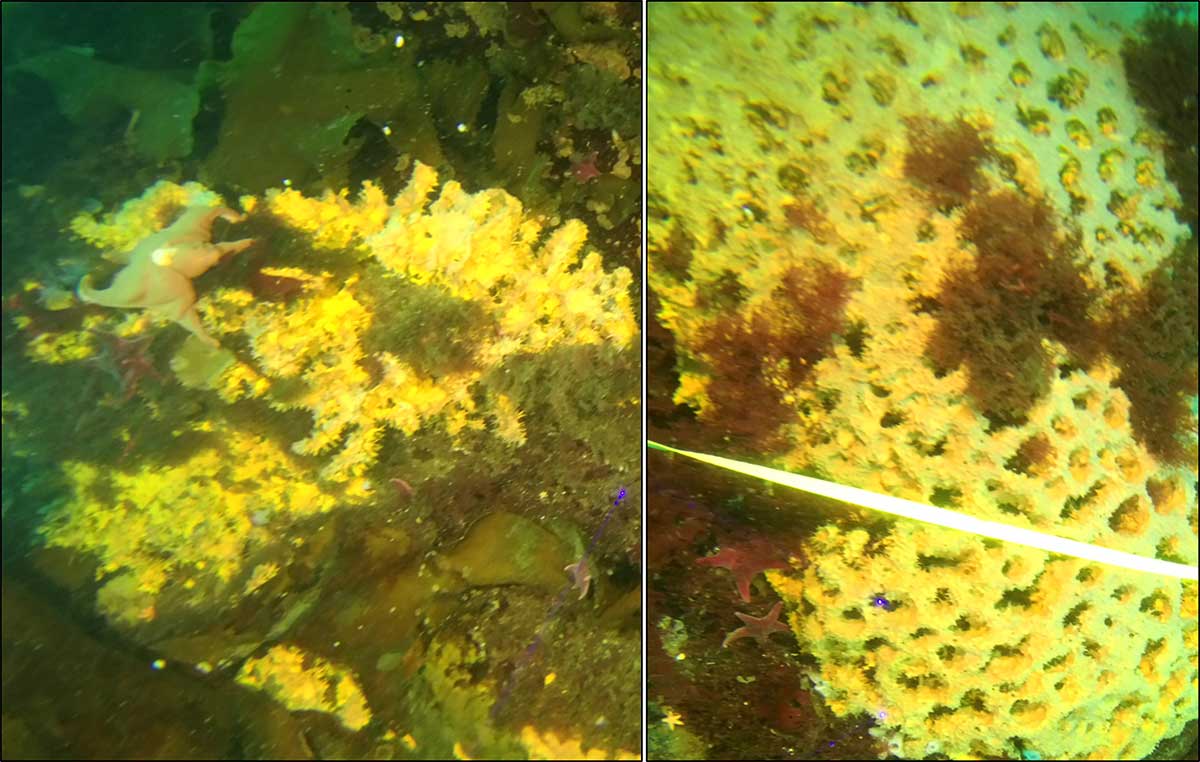

The shape of a single sponge species can vary a great deal. Dendrilla membranosa is one such shape-shifting sponge. Always screaming yellow in color its shape is sometimes short spiky arms in form earning it the nickname cactus sponge. Other times it forms flat mounds with short spikes. See the difference in the composite image below? No matter the shape, this sponge also produces numerous defensive chemicals. One in particular is called Darwinolide and its synthetic form also has attracted a huge interest as an antibacterial agent, especially against MRSA– a nasty staph infection and bane of gyms and hospitals. Healthier living based on natural products from sponges in Antarctica’s waters. (The band crossing over the mounded sponge is a tape measure. Chuck’s next entry will explain why we swim around with a tape measure.)

Soaked up enough sponge (pun intended)? OK let’s switch gears to the sedentary cousin of jellyfish and look at sea anemones. These could have been included in the first installment of All Creatures as their numerous tentacles, 160-190, qualify them as multi-armed – at least in my book. Those tentacles often contain stinging cells to stun small prey. The clownfish in the movie Finding Nemo and in reality too, is immune to the stings of its local anemone. Anemones only partially qualify as sedentary as their big foot, firmly attaching them to a hard surface, is capable of movement. I mentioned in the second installment of All Creatures that urchins can be lunch for an anemone. Given their Little Shop of Horror-like behavior, their flowery appearance it is best admired in its home environment.

Alongside the anemone and again above at the top, are yellowish barrel-shaped critters called ascidians. Each has warty skin and large siphons at either end. Similar to sponges, these guys feed by drawing seawater and microscopic goodies in one siphon and waste out of the other siphon. Commonly called sea squirts, children (of all ages) have been known to find individuals washed up on a beach and demonstrate the derivation of the moniker. They make a perfect all-natural squirt pistol!

Another fun fact about ascidians is that these critters are actually distant cousins of ours. The larval form of ascidians is free-swimming and resembles amphibian tadpoles. Appearances aside, the larval ascidians also have structural features common to vertebrates, frogs, and humans alike, that disappear once the larva settles down and metamorphoses into its attached adult form.

Palmer Station is currently metamorphosing. Winter is taking shape as it has been snowing since last night and the predictions are for more white stuff to come in the next few days. Good day to be a home body, sort of settled in place like creatures in this entry. Maybe tomorrow I can swap fins for skis but only after the zodiacs have been shoveled out.

(Editor’s note: The day after composing this entry a warm north wind and rain washed the snow away.)