By Sean Carter, MD (CMR)

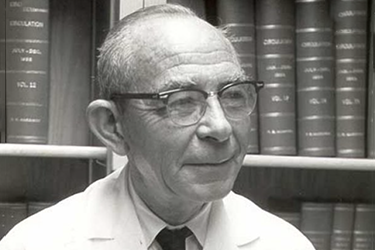

Image courtesy of UAB Archives

Image courtesy of UAB Archives

Dr. Glenn Cobbs is Professor Emeritus at UAB who obtained his medical degree from Harvard University in 1963. He then trained at UAB Hospital and Cornell prior to becoming an academic physician at UAB. He had the opportunity to train under Dr. Tinsley Harrison, the namesake of our letter series and the Internal Medicine Residency Program. I was able to sit down with Dr. Cobbs and reflect on his experience with Dr. Harrison.

Q: What are your first memories of Dr. Harrison?

A: Dr. Harrison moved to Birmingham in 1950 to work at UAB and had joined a country club where my father was a member. I first met him in social situations when I was 16 years old; he gave me some advice about pursuing a career in medicine. After I went to college for two years, I had the opportunity to round with Dr. Harrison in Jefferson Towers and was amazed by how sick the patients were. I did not continue premed after that and after college, I joined the U.S. Marine Corps and was in for four years. After the Marines, I went to medical school and came back as a house officer. I had the opportunity to serve on services where Dr. Harrison was the attending, and it was apparent what an extraordinary physician he was. Incidentally, in between the service and medical school, I was also able to work with him in his blood gas lab and went to conferences with him and his fellows.

Q: What advice did he give you prior to medical school?

A: Well. When I was pre-med and thinking about what to do, I was considering a mental health career. Dr. Harrison told me that if I was interested in mental health, Don’t think about being a psychologist, get a medical degree and become a psychiatrist. He emphasized that medical school was the way to go. Once I got into medical school…that prospect didn’t look so good, and I chose Internal Medicine

Q: How would you describe him as a clinician and a person?

A: He was unusual. He was different from any academic physician that I have ever encountered. I trained in Boston at Harvard Medical School, in New York for fellowship, and at UAB in academic medicine. I have encountered a lot of noteworthy physicians, but there were none like him. He had a classical background. He was a polymath and knew a lot about everything. His father was a physician, and during summers would take him on a one-to-two-month hike from Talladega to Atlanta. They would study trees, stars, or birds and more. He later studied in Germany.

His father had trained at Hopkins under Osler. He described his experience to Tinsley who became enamored with the idea of trying to emulate the kind of physician who was extremely capable and taught at the bedside. Dr. Harrison adopted that in spades, not only as a caretaker of patients, but as a teacher. He used the bedside to effectively teach medicine; it was unusual then and it is unusual now to carefully examine and talk to the patient and show the thought process to trainees. He would take a long time to do all that, but he was the best at that because he wanted to teach, and he had an encyclopedic knowledge of medicine. In the first edition of his textbook that he wrote with the editors, he said he basically knew everything that was in that book—neurology, hematology, infectious diseases, etc. Later, he said he stopped trying to keep up because his brain was “close to busting.” The first thing he decided not to know any more about was clotting. He said clotting was too complicated, to hell with it (laughs).

Q: How do you think his influence persists to this day?

A: His influence is both direct, in the individuals who he trained (but there aren’t many of us left), and in the institution in a kind of Zen sort of fashion. George Karam came back about 10 years ago and gave a grand rounds talk about Dr. Harrison’s legacy. He stated that the department of medicine should become more aware of what Dr. Harrison’s legacy was all about and adopt it. This led some of the things that we’re doing right now like the legacy dinner, the name of the residency and resident service.

He described an equation (E = hH2, Education equals Teacher’s head times Teacher’s heart squared) that is a “mathematical description” of what he thought was the most important part of teaching. He wanted to give a “cardiac transplantation” to the trainee. In other words, what he would like to transmit is his own enthusiasm for caring for the patient. He thought that all of the other things about teaching like transmitting knowledge was not as important as transmitting an ethic about how to take care of people. He felt that medicine was a priesthood that had to be transmitted to a trainee in order for them to do their best job. The mentor has to transmit to the trainee his feelings about what he is doing. He talked about a Contagious Fire that he always tried to identify in a physician; he thought that it was important for a mentor to be enthusiastic about medicine and transmit this to trainees.

Q: What advice do you think Dr. Harrison would give to the residents now?

A: I would say that you don’t really need Dr. Harrison’s advice on what to do. It’s not really knowing what to do that is the problem, but doing what is to be done to take care of people. You need knowledge and compassion to take care of people. The only two things you need to be a good physician is to know how to talk to people and when to look things up. If you talk to people and are interested in their lives, know where to look up things that will help them, you can be a good physician. He would also encourage residents to be fired up about teaching and to teach, like about clotting (laughs). Really, there’s just three things residents need to do: care about people, build your knowledge, and teach.