It began much like a rock band or a startup company: with a handful of true believers gathered in a small, dingy space who were willing to work tirelessly for a future filled with both promise and uncertainty.

It began much like a rock band or a startup company: with a handful of true believers gathered in a small, dingy space who were willing to work tirelessly for a future filled with both promise and uncertainty.

This was the scene in 1979 when UAB founded the Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME). The department consisted of four professors and a staff technician toiling together in Cudworth Building’s windowless basement.

“It was a truly terrible space,” recalls Linda Lucas, Ph.D., UAB’s first Ph.D. graduate in biomedical engineering who went on to serve as the BME department’s chair, the School of Engineering’s dean, and UAB provost. “I had to paint my office. Since there were no windows, I painted it a bright yellow.”

Now 40 years later, the department’s outlook has brightened considerably. BME covers three buildings with about 20,000 square feet of modern, well-equipped laboratory space. In 2014, it became a joint department of the School of Engineering and the School of Medicine, the only department with dual status at UAB.

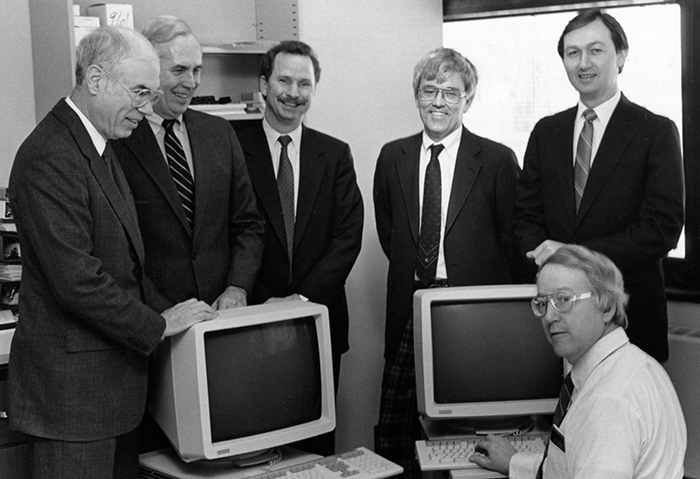

Jay Goldman (far left), and Louis Sheppard (second from left) watch fellow professor Martin McCutcheon (seated) demonstrate the university’s new expert system from Digital Equipment Corp., circa 1987The department has grown so much that it now consistently ranks in the top five nationally in National Institutes of Health research funding. From 2016-2018, the department ranked top 5 in NIH Blue Ridge Rankings. Moreover, several BME collaborations across schools have led to successful spinoff businesses throughout the years.

Jay Goldman (far left), and Louis Sheppard (second from left) watch fellow professor Martin McCutcheon (seated) demonstrate the university’s new expert system from Digital Equipment Corp., circa 1987The department has grown so much that it now consistently ranks in the top five nationally in National Institutes of Health research funding. From 2016-2018, the department ranked top 5 in NIH Blue Ridge Rankings. Moreover, several BME collaborations across schools have led to successful spinoff businesses throughout the years.

“In spite of the tiny faculty at the beginning, there was a strong cadre of M.S. and Ph.D. students,” says Ernest Stokely, Ph.D., who became the department’s second chair. “Since we had so few faculty members, it was only through collaborations in the School of Engineering and across UAB that we achieved research at critical mass to span several research areas.”

Lucas agrees that a spirit of collaboration has been key to the department’s growth. “From the very beginning of this program, partnerships from both sides of the campus were important,” she says. “There has always been strong collaboration between the engineering and medical programs, and BME couldn’t have succeeded without faculty who liked to work across campus.

Linda Lucas (left), Rose Scripa (second from left), and Martha Bidez (far right), with then-president of the Society of Women Engineers Suzanne Jenniches (second from right), present James Woodward (center) with the Rodney D. Chip Memorial Award from the Society of Women Engineers, circa 1989“We recruited students who saw that we were an engineering program with a very strong medical program. That was a strong recruiting tool for students and for faculty. From the get go, that has been our spirit and our driving force.”

Linda Lucas (left), Rose Scripa (second from left), and Martha Bidez (far right), with then-president of the Society of Women Engineers Suzanne Jenniches (second from right), present James Woodward (center) with the Rodney D. Chip Memorial Award from the Society of Women Engineers, circa 1989“We recruited students who saw that we were an engineering program with a very strong medical program. That was a strong recruiting tool for students and for faculty. From the get go, that has been our spirit and our driving force.”

The results have been impressive, with a number of BME faculty members and graduates making substantial contributions to the field. They include:

Martha Bidez, Ph.D., who founded the Birmingham-based dental implant company BioHorizons, which has had several BME graduates serve in leadership roles over the years. Bidez also pioneered BME’s Advanced Safety Engineering degree program and was named the International System Safety Society’s 2011 Educator of the Year.

Ken Solovay, M.S., B.S., who has worked for companies ranging from Johnson & Johnson to smaller startups such as Aspiration Medical Technology, where he brought an obesity treatment from concept through development and validation. Solovay has extensive experience developing implantable devices with minimally invasive delivery systems and holds 36 patents.

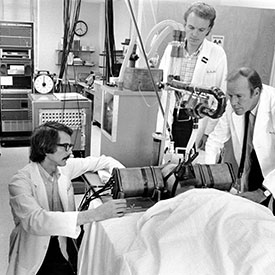

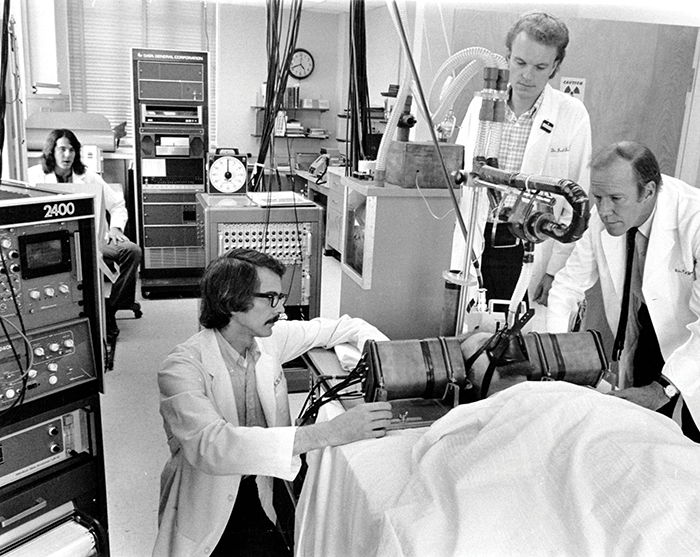

computer operator; Timothy Wick with a researcher pictured in Wick’s lab, circa 200Louis Sheppard, Ph.D., the first chair of BME, who developed computer-based systems for intensive care that utilized closed-loop, feedback control of cardiac and vascular pressures.

computer operator; Timothy Wick with a researcher pictured in Wick’s lab, circa 200Louis Sheppard, Ph.D., the first chair of BME, who developed computer-based systems for intensive care that utilized closed-loop, feedback control of cardiac and vascular pressures.

Sheppard was succeeded as BME chair in 1990 by Ernest Stokely, Ph.D., who expanded BME’s focus to include biomedical imaging. By the turn of the 21st century, UAB recruited Raymond Ideker, M.D., Ph.D., and his entire team from Duke University. This recruitment created new opportunities in the area of cardiac electrophysiology. Many of the team members have become leaders in the field of cardiac electrophysiology. Ideker is now professor emeritus in the Division of Cardiovascular Disease.

Timothy Wick, Ph.D., became department chair in 2005 and spent the next decade guiding the department through an era of tremendous growth. In particular, his efforts bolstered faculty recruitment, which in turn expanded extramural research funding, especially around tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Wick was also central to creating the strategic plan that led to the department’s most recent major transition.

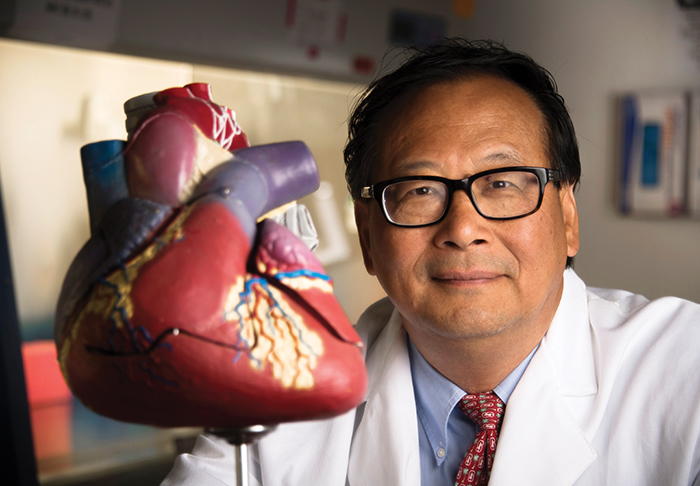

The department’s biggest change came in 2014 when BME joined forces with the School of Medicine. This enabled UAB to recruit Jianyi (Jay) Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., from the University of Minnesota Medical School to succeed Wick to become BME’s current chair. Zhang is an international leader in myocardial bioenergetics, biomaterial, and cell therapy for myocardial repair.

Raymond Ideker (pictured in 2001), an expert in cardiac electrophysiology, came to UAB from Duke University in the early 2000s and directed the Cardiac Rhythm Management Laboratory.“Engineers develop tools to benefit society, and medical research develops inventions that improve public health,” Zhang says. “So the convergence of these two schools was attractive to me because we can apply scientific discoveries to benefit society.”

Raymond Ideker (pictured in 2001), an expert in cardiac electrophysiology, came to UAB from Duke University in the early 2000s and directed the Cardiac Rhythm Management Laboratory.“Engineers develop tools to benefit society, and medical research develops inventions that improve public health,” Zhang says. “So the convergence of these two schools was attractive to me because we can apply scientific discoveries to benefit society.”

Through a $2.5 million NIH grant in collaboration with Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York and UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Zhang is leading research at UAB to discover ways to, as he puts it, “turn back the clock” on cardiac myocyte regeneration.

“One of the major reasons the heart fails is the loss of myocytes, a type of cell generate force and found in muscle tissue. That’s because we are born with a set number of myocytes, and they don’t regenerate,” Zhang says. “Myocytes continue to divide during the fetal stage, but they stop dividing after birth. When we lose enough of that muscle tissue, it causes heart failure to occur.

“So if we can understand the mechanisms of why the myocyte exits the cell regeneration cycle after birth, then we can manipulate the mechanisms to increase lost cardiac muscle mass due to a heart attack.”

As part of a seven-year, $8 million NIH grant, Zhang and UAB are also working with Duke University Medical Center and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health on cell therapy research to create a cardiac “muscle patch” for patients who have experienced a heart attack. “We want to use a patient’s own stem cells to generate more cardiomyocytes,” Zhang says. “That way we can engineer tissue to patch on to the heart with a patient’s own cardiac-fabricated tissue to prevent further dilation of the heart.”

This type of cutting-edge research might have seemed impossible four decades ago, when the first BME faculty members say they were simply trying to spruce up the walls of their offices.

Jianyi (Jay) Zhang joined the BME department as chair in 2014, when the department became a joint department between the Schools of Medicine and Engineering. “It’s amazing how much the program has grown in both quality and strength,” Lucas says. “And it’s not just the numbers, but it is also the kinds of problems they’re addressing in a very interdisciplinary way. It would have been hard to believe 40 years ago when I was sitting in that basement at Cudworth that all this would have happened.”

Jianyi (Jay) Zhang joined the BME department as chair in 2014, when the department became a joint department between the Schools of Medicine and Engineering. “It’s amazing how much the program has grown in both quality and strength,” Lucas says. “And it’s not just the numbers, but it is also the kinds of problems they’re addressing in a very interdisciplinary way. It would have been hard to believe 40 years ago when I was sitting in that basement at Cudworth that all this would have happened.”

By Cary Estes

It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll

Rarely do the worlds of rock ’n’ roll and bioengineering collide. But this odd convergence has been a regular occurrence since 2003, each time the band BEDrock—founded in part by two current UAB BME professors—takes the stage.

Alan Eberhardt, Ph.D., professor and associate chair, and Joel Berry, Ph.D, associate professor, are regular members of the band, which consists of a rotating list of bioengineering professors from across the globe who perform at major bioengineering conferences. It began as something of a lark at the 2003 conference for the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Bioengineering Division—the BED in BEDrock—but quickly grew to become one of the conference’s most anticipated events.

“Our first gig was at a conference in Miami. We played at the student center, and there were maybe 40 people there,” Eberhardt says. “In 2014, we played at the House of Blues in Boston in front of 2,000 people.”

“Our first gig was at a conference in Miami. We played at the student center, and there were maybe 40 people there,” Eberhardt says. “In 2014, we played at the House of Blues in Boston in front of 2,000 people.”

Eberhardt says the band’s lineup changes every year, with different professors and even some students joining a jam session that consists heavily of classic rock covers (Rolling Stones, Tom Petty, etc.). The band has swelled to as many as 19 people and has included participants from England, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

Once the lineup is established for the current year, each member practices on their own. They then get together for a single group practice session at the conference the night before they perform.

“There are moments where you’d think we’re a professional band, and then there are other moments where it’s obvious we practiced only one time,” Eberhardt says, laughing. “It’s just something we do for fun.”

“With BEDrock, we found a way to make other bioengineers dance, which is not an easy thing to do,” adds Berry.