In This Issue: Service Learning Brings Medical Training to Community

With the opening of the School of Medicine's Office of Service Learning, service learning is being formally incorporated into the school's curriculum. Learn why service learning is increasingly emphasized in medical education, and read about the benefits both students and the community reap from our new service learning programs, which include a new Alabama chapter of the Albert Schweitzer Fellowship.

With the opening of the School of Medicine's Office of Service Learning, service learning is being formally incorporated into the school's curriculum. Learn why service learning is increasingly emphasized in medical education, and read about the benefits both students and the community reap from our new service learning programs, which include a new Alabama chapter of the Albert Schweitzer Fellowship.

To support the School of Medicine's service learning initiatives, please contact us.

Volume 42, Number 3

Connecting the Dots: Service learning takes medical training out of the classroom and into the community

Craig Hoesley, senior associate dean for medical education, and Caroline Harada, assistant dean for community-engaged scholarship. Medical students’ days are a constant rush of workshops, lectures, and textbooks, and their evenings are spent deciphering the meaning of seven-syllable words and memorizing that the hand bone is connected to the distal phalange bone. But there is another part of being a physician that can fade from view as students tackle the monumental learning challenges of medical school; the part that is described in the Hippocratic Oath as the “art of medicine,” where “warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.” The part that can be referred to simply as service.

Craig Hoesley, senior associate dean for medical education, and Caroline Harada, assistant dean for community-engaged scholarship. Medical students’ days are a constant rush of workshops, lectures, and textbooks, and their evenings are spent deciphering the meaning of seven-syllable words and memorizing that the hand bone is connected to the distal phalange bone. But there is another part of being a physician that can fade from view as students tackle the monumental learning challenges of medical school; the part that is described in the Hippocratic Oath as the “art of medicine,” where “warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.” The part that can be referred to simply as service.

In recent years, the School of Medicine has worked to better integrate these two aspects of being a physician into the school’s curriculum. Students still must accumulate an enormous amount of “book learning,” but they also need to learn how important compassion is to the practice of medicine, and the ways that health care (and lack thereof) affects people’s lives in the world outside the lecture hall. In other words, they need to combine both service and learning.

Read moreNew Beginnings: Introducing the Class of 2020

Each August, the School of Medicine welcomes its incoming class with the White Coat Ceremony. The ceremony marks the end of medical school orientation and the students’ first class, “Patient, Doctor and Society,” which emphasizes professionalism, compassion, responsibility, ethics, and the doctor/patient relationship. In addition to receiving their white coats, which are provided by the school’s Medical Alumni Association, the day marks a major milestone on the path to becoming a physician. Being accepted to medical school and participating in the White Coat Ceremony is a remarkable achievement; the School of Medicine is privileged to walk with these students on the journey of knowledge and self-discovery that they are just beginning.

Each August, the School of Medicine welcomes its incoming class with the White Coat Ceremony. The ceremony marks the end of medical school orientation and the students’ first class, “Patient, Doctor and Society,” which emphasizes professionalism, compassion, responsibility, ethics, and the doctor/patient relationship. In addition to receiving their white coats, which are provided by the school’s Medical Alumni Association, the day marks a major milestone on the path to becoming a physician. Being accepted to medical school and participating in the White Coat Ceremony is a remarkable achievement; the School of Medicine is privileged to walk with these students on the journey of knowledge and self-discovery that they are just beginning.

Practice Makes Perfect: The evolving role of the UAB Clinical Skills Center

Shawn Galin became director of the Clinical Skills Center last winter and is overseeing its transition to a campus-wide resource and a place for a variety of health professions students to interact. Since becoming director of the UAB Clinical Skills Center last December, Associate Professor of Medicine Shawn Galin Ph.D., has been overseeing a change that will bring the center under the governance of UAB’s new Center for Interprofessional Education and Simulation (CIPES).

Shawn Galin became director of the Clinical Skills Center last winter and is overseeing its transition to a campus-wide resource and a place for a variety of health professions students to interact. Since becoming director of the UAB Clinical Skills Center last December, Associate Professor of Medicine Shawn Galin Ph.D., has been overseeing a change that will bring the center under the governance of UAB’s new Center for Interprofessional Education and Simulation (CIPES).

The Clinical Skills Center is where medical students taking Introduction to Clinical Medicine practice skills such as taking patient medical histories and performing physical examinations. It is also the testing space for medical students taking their Objective Structured Clinical Exams (OSCE). The Center has 20 exam rooms outfitted with audio and visual recording equipment. During medical simulations, instructors watch students’ performances on TV monitors in a nearby room. Afterward, students are debriefed and offered instruction on how to improve their clinical skills and bedside manner.

Read moreJoining Forces: A powerful alliance between UAB and the Birmingham VA enriches residency training

From left: Louis Dell'Italia, associate chief of staff for Research at the BVAMC and professor of medicine in the UAB Division of Cardiovascular Disease; Susan Laing, associate chief of staff for education at the BVAMC; and Gustavo Heudebert, assistant dean of graduate medical education at the School of Medicine.When WWII ended in 1945, thousands of returning soldiers sought medical treatment through the Department of Veterans Affairs. To meet the challenge of providing quality care for those who had served, the VA established an association with academic medical schools. On January 30, 1946, an agreement called Policy Memorandum #2 was issued to formalize this alliance. This year marks the 70th anniversary of the partnership.

From left: Louis Dell'Italia, associate chief of staff for Research at the BVAMC and professor of medicine in the UAB Division of Cardiovascular Disease; Susan Laing, associate chief of staff for education at the BVAMC; and Gustavo Heudebert, assistant dean of graduate medical education at the School of Medicine.When WWII ended in 1945, thousands of returning soldiers sought medical treatment through the Department of Veterans Affairs. To meet the challenge of providing quality care for those who had served, the VA established an association with academic medical schools. On January 30, 1946, an agreement called Policy Memorandum #2 was issued to formalize this alliance. This year marks the 70th anniversary of the partnership.

“There wasn’t a way to take care of all of the soldiers who came to the VA seeking medical treatment after the war,” says Susan J. Laing, Ph.D., associate chief of staff for education at the Birmingham VA Medical Center (BVAMC). “So the memorandum gave physician residents an opportunity to train and help provide care for veterans. It has been a very valuable partnership—a wonderful marriage between academic medical centers like UAB and the Department of Veteran Affairs.”

Read moreConfronting Health Inequity: New medical students learn about social determinants of health

Spenser Hayward admits he had only a surface understanding of the connections between poverty and health before he started medical school in August 2015. Hayward and about 50 of his new classmates arrived on campus a few days before the start of medical school orientation to participate in the first-ever Health Disparities Boot Camp, which was sponsored by the School of Medicine’s Office of Diversity and Multicultural Affairs. The group learned about the profound impact that income can have on a person’s health. “I wanted to become more culturally self-aware, and better able to understand the differences between my experience and that of my future patients,” Hayward says.

Spenser Hayward admits he had only a surface understanding of the connections between poverty and health before he started medical school in August 2015. Hayward and about 50 of his new classmates arrived on campus a few days before the start of medical school orientation to participate in the first-ever Health Disparities Boot Camp, which was sponsored by the School of Medicine’s Office of Diversity and Multicultural Affairs. The group learned about the profound impact that income can have on a person’s health. “I wanted to become more culturally self-aware, and better able to understand the differences between my experience and that of my future patients,” Hayward says.

A Matter of Principle: Small groups offer ideal setting for medical ethics instruction

As a Learning Communities faculty mentor, Todd Peterson (left) leads small group discusions about medical ethics. Mariko Nakano (right), assistant professor of bioethics, created much of the school’s new medical ethics curriculum. At the intersection of medicine and morality lies medical ethics, a system of principles that guides how physicians apply values and judgments to their practice. But determining the best way to teach medical ethics can be tricky. In the last few years, the School of Medicine realized that holding occasional ethics teaching sessions with an entire 180-person class wasn’t conducive to meaningful dialogue. Aside from those large group discussions, it has traditionally been left to faculty members to incorporate ethics lessons into the regular curriculum.

As a Learning Communities faculty mentor, Todd Peterson (left) leads small group discusions about medical ethics. Mariko Nakano (right), assistant professor of bioethics, created much of the school’s new medical ethics curriculum. At the intersection of medicine and morality lies medical ethics, a system of principles that guides how physicians apply values and judgments to their practice. But determining the best way to teach medical ethics can be tricky. In the last few years, the School of Medicine realized that holding occasional ethics teaching sessions with an entire 180-person class wasn’t conducive to meaningful dialogue. Aside from those large group discussions, it has traditionally been left to faculty members to incorporate ethics lessons into the regular curriculum.

Now, ethics and other topics are being taught in small groups called Learning Communities. On the first day of medical school, students are assigned to a Learning Community comprised of about 18 students from all classes. “The main purpose of a Learning Community is to provide a safe, comfortable environment where a student can thrive for four years,” says faculty mentor Todd B. Peterson, M.D., associate professor of emergency medicine. The Learning Communities model also offers a better way to address topics like ethics, service learning, stress management, and others, Peterson says.

Read moreScholarship Voices: Medical students share their paths to medical school and their plans for the future

Serving Locally and Globally

This year third-year class president Salmaan Kamal became the second Finley Scholar.Third-year medical student Salmaan Kamal probably never imagined that his pre-med education would include helping coordinate the logistics of a goat delivery service. Raised in Tuscaloosa, where his parents practice medicine—his father is an endocrinologist and his mother a cardiologist—Kamal’s senior project at Princeton University took him to Sierra Leone, where he researched the accuracy of malaria diagnostic tests at a free clinic run by Wellbody Alliance. The experience included helping Wellbody establish a goat farming initiative, by transporting live goats to farmers via motorcycle.

This year third-year class president Salmaan Kamal became the second Finley Scholar.Third-year medical student Salmaan Kamal probably never imagined that his pre-med education would include helping coordinate the logistics of a goat delivery service. Raised in Tuscaloosa, where his parents practice medicine—his father is an endocrinologist and his mother a cardiologist—Kamal’s senior project at Princeton University took him to Sierra Leone, where he researched the accuracy of malaria diagnostic tests at a free clinic run by Wellbody Alliance. The experience included helping Wellbody establish a goat farming initiative, by transporting live goats to farmers via motorcycle.

Kamal was selected as the 2016 recipient of the Sara Crews Finley, M.D., Endowed Leadership Scholarship. The scholarship, which was established by Dr. Finley’s family to support students who demonstrate exceptional academic and leadership abilities, honors the legacy of pioneer in medical genetics and a beloved faculty member and student mentor. “It is humbling to be recognized as someone with the integrity to carry out that legacy of service,” Kamal says.

Read moreTools of the Trade: The evolution of medical training aids

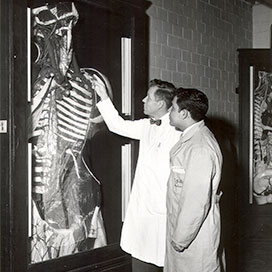

Henry H. Hoffman, M.D., and student Manuel De Los Santos view a papier mache anatomical model, circa 1950. Hoffman was a professor in the anatomy department after 1957. While computer-based learning modules and high-tech gadgetry are central to medical training today, nothing compares to a physical object you can hold and inspect closely to arouse curiousity and a passion for discovery. Presented here are a few training tools and methods from the School of Medicine's past that still inspire fascination.

Henry H. Hoffman, M.D., and student Manuel De Los Santos view a papier mache anatomical model, circa 1950. Hoffman was a professor in the anatomy department after 1957. While computer-based learning modules and high-tech gadgetry are central to medical training today, nothing compares to a physical object you can hold and inspect closely to arouse curiousity and a passion for discovery. Presented here are a few training tools and methods from the School of Medicine's past that still inspire fascination.