When it is not possible to get a severely injured patient to the hospital quickly enough, the best solution may be to bring the hospital to the patient. That was the thinking behind the development in 2019 of the UAB SWIFT Team (Surgical forWard Intervention for Trauma), which enables doctors to perform life-saving procedures directly at the scene.

When it is not possible to get a severely injured patient to the hospital quickly enough, the best solution may be to bring the hospital to the patient. That was the thinking behind the development in 2019 of the UAB SWIFT Team (Surgical forWard Intervention for Trauma), which enables doctors to perform life-saving procedures directly at the scene.

This initiative was employed in the most dramatic fashion during the wee hours of January 25. After an EF-3 tornado ripped through the Birmingham suburb of Fultondale, a UAB trauma and emergency medicine team performed a leg amputation to free a man who was pinned underneath a massive oak tree that had fallen through his home.

“The SWIFT team has the capability to basically carry an operating room on their backs out into the field, where minutes can determine whether somebody survives or dies,” says Jeffrey Kerby M.D., Ph.D., director of the UAB Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. “Moving out of the hospital to where the injury happened in order to save those minutes was the impetus for this whole program. It’s so gratifying to see the vision we had for it actually result in a life saved.”

Answering the Call

On the night of the Fultondale tornado, area Fire Rescue and Paramedic teams were on site trying to free Arnoldo Vasquez-Hernandez, a father of three, from underneath the tree that had pinned him. They were on the phone receiving advice from two UAB doctors: Donald Reiff, M.D., Trauma and Acute Care surgeon, and Blayke Gibson, M.D., Emergency Medicine physician.

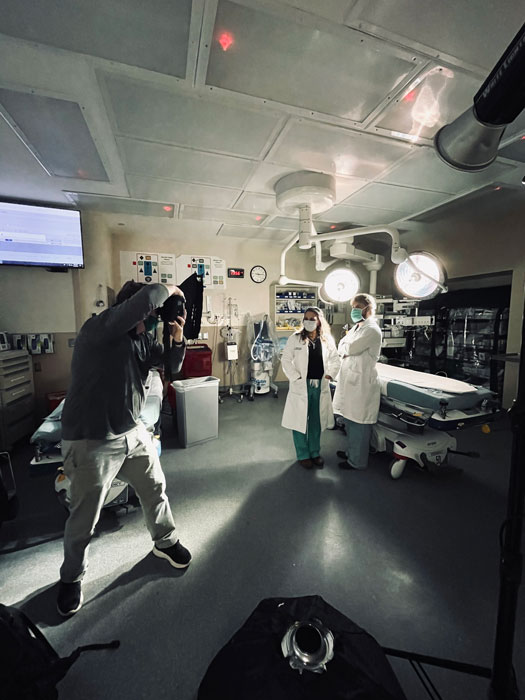

After more than two hours of unsuccessful attempts, the first responders became concerned. Not only was Vasquez-Hernandez in dire need of medical care, but the house appeared to be growing increasingly unstable. “I could hear the desperation in their voices,” Gibson says. “They just didn’t really know what to do.” Blayke Gibson, an Emergency Medicine physician, and Donald Reiff, a Trauma and Acute Care surgeon.

Blayke Gibson, an Emergency Medicine physician, and Donald Reiff, a Trauma and Acute Care surgeon.

A team from UAB was dispatched to evaluate the situation and determine whether an on-site amputation was needed and could be performed. In addition to Blayke and Reiff, the team included Sherichia Hardy (trauma and burn nurse manager) and India Alford (director of nursing services at UAB Medicine’s Gardendale Freestanding Emergency Department).

“We prepared all the equipment that the surgeon might need from the OR, and other supplies that we might need from the emergency department,” Gibson says. “We packed up airway supplies, drugs, a blood cooler, and blood.

“The nurses put everything together, the other attendings and residents in the department took over to cover my patients, and UAB police transported us to the scene with all the equipment. It was an incredible team effort between trauma, emergency medicine, nursing, and UAB police.

A Perilous Procedure

Once on site, the team entered the house through the basement and managed to get close enough to Vasquez-Hernandez to examine him and let him know an amputation was necessary. But the team could not get close enough to perform the procedure, so they had to enter through the front of the house and work their way through the wreckage, with an instrument tray and other equipment in hand.

“We dosed him up with a bunch of ketamine, and then it took me about 20 minutes to get the tourniquets on his legs because of the way his leg was trapped,” Reiff says. “If we’d lost control of the tourniquet there could have been a lot of active hemorrhage, and that would have been dangerous.

“We dosed him up with a bunch of ketamine, and then it took me about 20 minutes to get the tourniquets on his legs because of the way his leg was trapped,” Reiff says. “If we’d lost control of the tourniquet there could have been a lot of active hemorrhage, and that would have been dangerous.

“At one point the fire chief stuck his head in and was like, ‘Hey, I just want to let you guys know that the house is becoming progressively more unstable.’ So you’re just moving as fast as you can to get him out of that, but you still have to deal with the bleeding.”

While all this was taking place, Gibson had to keep the patient sedated, which also was a tricky procedure. “We didn’t have a ventilator or anything, so throughout the procedure we had to bag him and continue to administer drugs,” she says. “It wasn’t like an OR. We didn’t have IV drips or anything, I just was pushing boluses of medications to try to keep him appropriately sedated.”

Despite the difficult and dangerous conditions, the above-the-knee amputation itself took only about 10 minutes to complete. The rescue team was finally able to extract Vasquez-Hernandez and carry him to the ambulance, though even that was proved to be no easy task.

“Because of all the mud and debris, you really couldn’t walk. You would just slide everywhere,” Gibson says. “So the firemen formed two lines and passed him from person to person on the basket up the hill until they got him in the ambulance.

“The two nurse managers and I got in the ambulance with him and continued to provide the sedation to keep him under throughout the transport. We were able to give him blood and get another IV started. We transported him to UAB, where I’ve never been so excited in my life to see the trauma bay doors.”

A Team Effort

Vasquez-Hernandez is recovering from his injuries, and the team believes he will have an opportunity to live a normal life, possibly with the use of a prosthetic leg.

While it was a harrowing night for all those involved, it also confirmed the value of the SWIFT Team. Kerby says Reiff has been integral in building the program and expanding its capabilities, drawing on experiences and relationships with both military and law enforcement officials.

“UAB has had a long-term affiliation with the military, especially with our division of trauma,” Kerby says. “A lot of what our military partners have done with the special operations surgical teams is pushing capabilities outside the hospital setting and into more austere environments. So we’re now taking techniques like advance hemorrhage control, resuscitation, and even stabilizing surgery out of the hospital and closer to the incident.

“This response was a great success, and certainly fits right into what we were hoping to build on with these capabilities. Because doing this work in the field definitely has the potential to save lives. Hopefully we can continue to build on the program, and if a situation like this ever arises again, we will have the capability to address it.” – Cary Estes