As we embarked on the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic in Alabama, we asked people from across the School of Medicine to take part in conversations about what they had learned from the past year, and what they see when they look ahead to the future. The following are excerpts of those conversations, which have been edited for clarity.

As we embarked on the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic in Alabama, we asked people from across the School of Medicine to take part in conversations about what they had learned from the past year, and what they see when they look ahead to the future. The following are excerpts of those conversations, which have been edited for clarity.

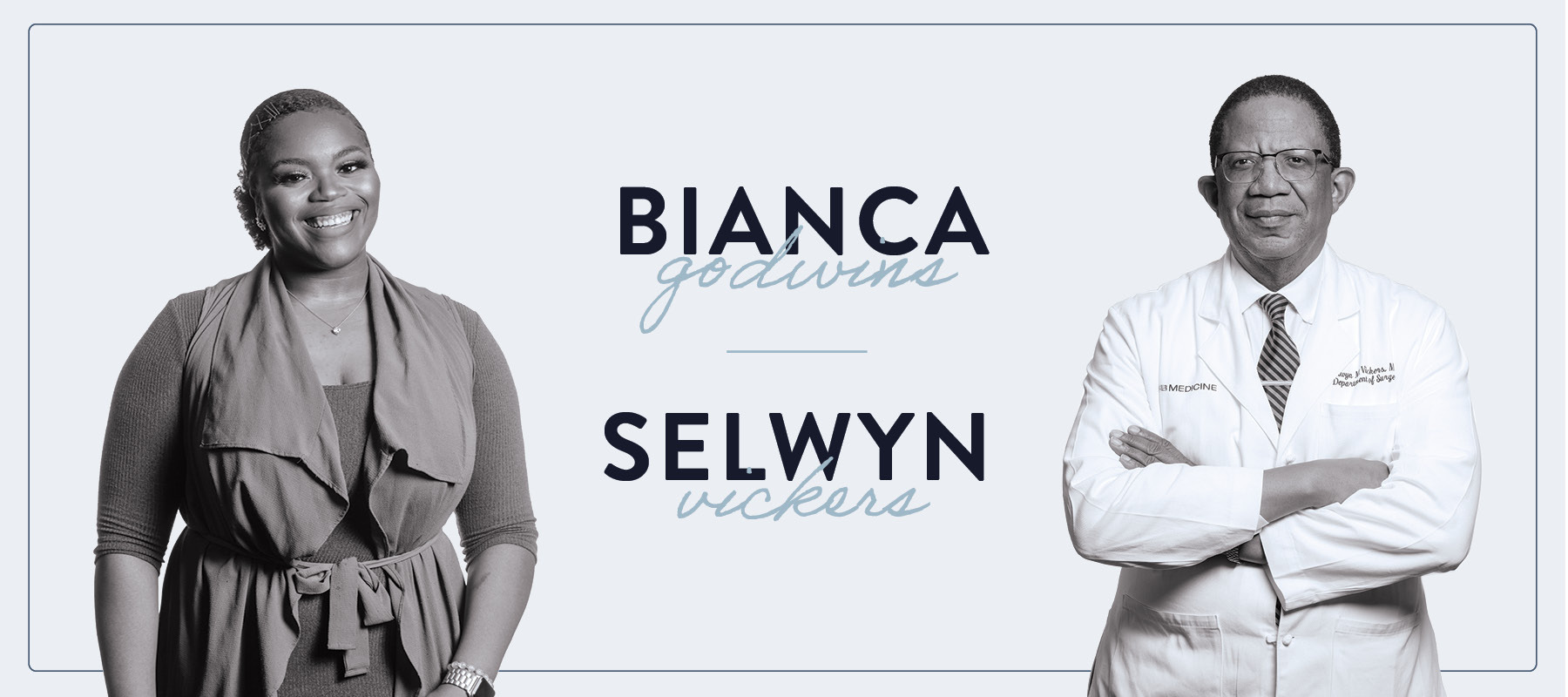

Bianca Godwins is a rising third-year medical student who is enrolled in the school’s M.D./MBA dual degree program. During the pandemic, Godwins has managed a team of undergraduate, graduate, and medical students who work as contact-tracers as part of a program between the UAB School of Public Health and the Alabama Department of Public Health. Selwyn Vickers, M.D., FACS, is senior vice president of Medicine and dean of the UAB School of Medicine. He also serves as chair of The University of Alabama Health Services Foundation. A renowned surgeon, pancreatic cancer researcher, and pioneer in health disparities research, Vickers is a member of the National Academy of Medicine and in April started a term as president of the American Surgical Association. We asked Vickers and Godwins to discuss COVID19 and health disparities, what Godwins learned through contact tracing, leading during a pandemic, and what it’s been like to be a medical student during the pandemic.

Vickers: So tell me Bianca, what are some of the things you learned in the past year?

Godwins: I think the biggest lesson I learned was, nothing matters in terms of all you’re striving for if you’re not healthy. Honestly, it made me love other people more, because we all come from different walks of life, but nothing matters if we’re not healthy and alive to experience the joy of all that we’re striving toward.

Vickers: There’s no doubt suffering and pain level the playing field for everybody, right? But you also highlight the fact that that for certain groups, the impact of the virus and their ability to recover are very different. And that difference is often based on what a person’s life looked like before the pandemic. Which leads me to ask, how did your volunteer work doing contact tracing during the pandemic affect your perspective?

Godwins: It’s opened my eyes to just how much more difficult dealing with the virus is for some people than others. The types of people we talk to on the phone can be really different in terms of where they come from and what they’re experiencing. One patient might live in an affluent community and be able to afford to go to the doctor or get a COVID test, or even just stay home and quarantine more easily. But, as an example, another patient one of my investigators and I interacted with was pregnant and was infected with coronavirus. She didn’t want to take off of work as we advised because she worked at a fast food restaurant and was afraid her supervisor would be mad because they were understaffed. So she was in a difficult position of, do I choose my health and the health of my child? Or do I choose my source of income?

Vickers: So, how have you used your voice to help your classmates who may not have had the journey and experience that you’ve had to understand disparities?

Godwins: Being in the midst of all that happened last year around racial injustice and experiencing all that’s going on with COVID and the type of patients that have been disproportionately affected, it’s really made me understand how there has to be a perspective change in order to be able to make the changes that we need to in our society right now. With all of the division that’s going on in this country, it’s easy to fall into the trap of not wanting to pay attention to what those around you are experiencing. But there has to be united front. I’m just hoping that being transparent about my experience, that hearing my story or hearing the stories of the patients that I’ve talked to, it’ll touch that light and make people want to join arms in ending this pandemic. Building on that, I’d like to ask you, if you could change one thing to make health care more accessible to underserved populations, what would that be?

Vickers: If I look back at history, what has affected disparate communities in this country more than anything, including their health care, is education. The greatest single factor that determines the health outcome of a family is the education level of the mother. So if I could change anything, it would be changing the quality of education and the value of getting an education. The thing that allowed my ancestors to separate themselves from poverty, was, one, hard work, and the other was the value they placed on education. So even if they couldn’t get it themselves, they made sure those who came next in line would because they knew it would give them a foot in the door to opportunity.

Godwins: So the last thing I’d like to ask, how has COVID-19 affected you, both as a leader and as a surgeon in the hospital on a day-to-day basis?

Vickers: As far as leading during COVID goes, I think not being able to completely connect with other leaders has been especially hard. I also think an aspect of working with patients in COVID that has been really hard is the inability to care for the person and their loved ones. Under normal circumstances, there is usually is a group of family members who come to the hospital daily, but because of the pandemic, you don’t get to really connect or, in some ways, minister to the whole family as you take care of their loved one. That’s important when things are looking good, but is even more important when they are not looking good.