Few figures did more to improve Alabama’s emergency health care system during the 1960s than Alan Dimick, M.D. ’58. He was on the front lines, with achievements that include integrating the hospital’s emergency rooms, establishing the UAB Burn Unit, and pushing for the creation of a modern paramedics service.

Few figures did more to improve Alabama’s emergency health care system during the 1960s than Alan Dimick, M.D. ’58. He was on the front lines, with achievements that include integrating the hospital’s emergency rooms, establishing the UAB Burn Unit, and pushing for the creation of a modern paramedics service.

When Dimick finished his surgical training in 1963, he went to work under Champ Lyons, M.D., then chair of the Department of Surgery. Lyons charged his young protégé with heady new responsibilities. “He said, ‘I’m going to give you two jobs,’” Dimick remembers. “‘The first is to start a burn center. The second is, I want you to combine the black and white emergency departments.’”

That conversation took place at the height of the civil rights movement in 1963. At the time, African-American patients were treated in the old Hillman Emergency Room—known as ‘the hole’—while white emergency patients were treated on another side of the hospital. As a result, staff and resources were stretched thin, and patients often waited an hour or longer to see a doctor. “It was bad medicine,” Dimick says. “We had to change people’s thinking, but we gradually worked through all that.”

Alan Dimick

Alan Dimick

Outside the hospital, racial turmoil raged on. Dimick says he will never forget the call he received Sunday, Sept. 15, 1963. “I was cutting the grass at home when the hospital called and said there had been a bombing at a church. I drove in and it was a horrific thing, as you can imagine,” he says. Four girls—Addie Mae Collins (14), Denise McNair (11), Carole Robertson (14), and Cynthia Wesley (14)—died in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing. As part of the team that pronounced the deaths of the girls, Dimick was tasked with informing the parents that their daughters had died.

Dimick’s father influenced his interest in medicine and burn care. “My father and grandfather were in the iron and steel business,” he says. “Iron melts at 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and back then they didn’t have good protection. Quite often a worker would get a ladle-full of iron spill or slosh and get burns. And my father was busy taking care of these burns in his office or taking them to the doctor’s office, so I frequently was involved in burn care.”

Dimick remembers burn care in the ’60s as primitive by today’s standards. “At that time … they were just putting Vaseline or some sort of ointment on (wounds). The smell was horrible, and the burns frequently got infected. A lot of patients died.”

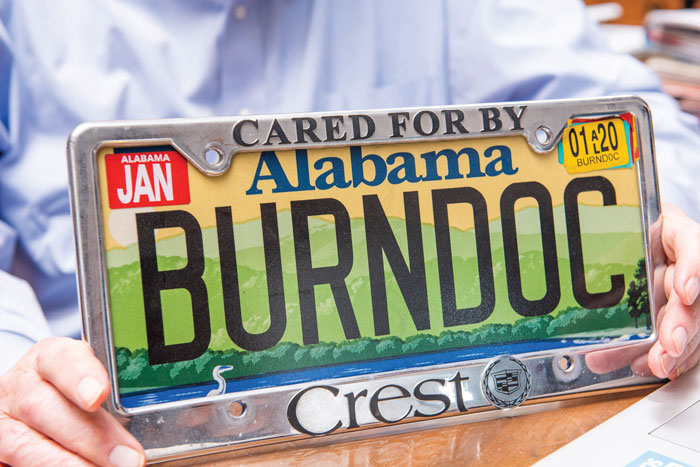

Dimick’s license plate reflects his lifelong commitment to burn care. Dimick established and became director of the UAB Burn Unit in 1970. “You can’t be a pessimist and take care of burns,” he continues. “You have to be an optimist.” Soon enough, new topical antibiotics were introduced, improving burn care dramatically. The Burn Unit also got its own ward with a dedicated staff specially trained in burn care.

Dimick’s license plate reflects his lifelong commitment to burn care. Dimick established and became director of the UAB Burn Unit in 1970. “You can’t be a pessimist and take care of burns,” he continues. “You have to be an optimist.” Soon enough, new topical antibiotics were introduced, improving burn care dramatically. The Burn Unit also got its own ward with a dedicated staff specially trained in burn care.

Beyond burns, Dimick worked to improve all types of trauma care, with a focus on training the people we now know as first responders. Nothing resembling modern-day paramedics existed then. “Ambulances at that time were station wagons run by funeral homes,” Dimick recalls, “Drivers had no training whatsoever, not even first aid. Once a driver bragged how he had dragged a man with a broken back 50 yards and threw him in the back of the station wagon. The man had major complications as a result.

“That motivated us to get better training for the people responding to trauma. Through the state department of health, we established an emergency medical service system, and the legislature finally passed the EMS law for training EMTs and paramedics.”

In 1972, Dimick became medical director of a federal grant that provided funds for emergency medical training for 33 firefighters in the fire departments of Birmingham, Homewood, and Vestavia Hills. These 33 firefighters were the first paramedics in Alabama. Since then, the paramedic program has grown to cover the state. UAB started its own paramedic training program and Dimick served as its medical director from 1975-1995. His influence can still be felt in the Birmingham emergency medical services community today. He currently serves on the board of the Birmingham Regional Emergency Medical Services System, the organization responsible for the overall coordination of and improvements in the pre-hospital emergency medical care of a seven-county region.

Dimick’s work in burn care is likely to remain his proudest legacy, though. He was the UAB Burn Unit director until 1997, and he remains dedicated to its cause. Dimick continues to attend—and often chair—American Burn Association conferences, where the highlight for him is visiting the burn centers at different host sites. “Everyone is doing some kind of research; thank goodness,” he says. “I always learn something new.”

By Rosalind Fournier

Honoring a Legacy

In 2018, the Medical Alumni Association (MAA) renamed its longstanding Perpetuity Fund in honor of Alan Dimick, M.D. Dimick was MAA president from 1967-1968 and treasurer from 1998-2012. The Perpetuity Fund helped fund the Volker Hall Student Study Lounge renovation, provided the lead gift to the Wayne H. Finley Genetics Travel Award, and helped refurbish furniture on Volker Hall Plaza. To give to the Alan R. Dimick, M.D., Medical Alumni Association Perpetuity Fund, call (205) 908-7004 or email office@alabamamedicalalumni.org.

The Alan R. Dimick Burn Care Fund supports the work of the UAB Burn Unit, which Dimick founded. The UAB Burn Unit is a nationally recognized leader in the treatment of burn-related injuries. It is committed to providing the highest-quality patient care, educating the next generation of surgeons, and conducting groundbreaking burn care research. To give to the UAB Burn Care Fund, please click here.