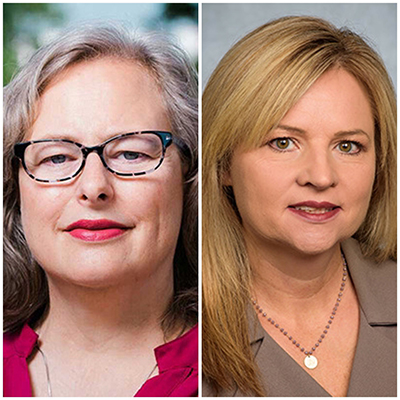

Karen Cropsey, Psy.D. (left) and Karen Gamble, Ph.D. (right)

Karen Cropsey, Psy.D. (left) and Karen Gamble, Ph.D. (right)

Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., and Karen Gamble, Ph.D., professors in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, have received a new grant totaling $4.4 million over a 4-year period to support their study “Medications for opioid use disorder differentially modulate intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell function, sleep, and circadian rhythms: implications for treatment.”

This study investigates why individuals with opioid use disorder, who are maintained on opioids for treatment, often suffer from poor sleep. While the connection between opioid use and sleep problems is well-known, the underlying biological mechanisms remain unclear.

“Previous research in mice has shown that opioids quickly metabolize in the bloodstream and brain but persist at high levels in the eye. This is particularly important because it can affect cells called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs),” said Gamble. “These cells express opioid receptors called mu receptors, and these cells in the eye are essential for regulating circadian rhythms (the body's natural sleep-wake cycle). When opioids activate the receptors, normal function of the ipRGCs is shut down, potentially leading to sleep disturbances.”

Q: What inspired you both to conduct this research/project?

Gamble:

Our close collaboration and frequent discussions on the intersection of circadian rhythms, sleep, and addiction motivated us to delve into this research. During a neuroscience meeting, I learned that opioid receptors disrupt ipRGCs in mice, prompting us to consider its potential implications in humans. We hypothesize that different opioid medications used to treat opioid use disorder may affect the sleep-wake cycle differently.

We swiftly identified an NIH funding opportunity and assembled an interdisciplinary team that included Dr. Paul Gamlin, a world-renowned scientist and expert on ipRGC and retinal function in humans and primates. Dr. Gamlin has developed an assay for ipRGC function in people, and he agreed that we had a great idea and was eager to join our team. Our proposal was one of four projects funded by the NIH.

Q: How will your research impact the science community at UAB?

Cropsey:

Our project highlights UAB's unique ability to unite as a multidisciplinary team, fostering a collaborative spirit to enhance patient well-being through scientific advancements. It serves as a prime example of how insights from animal studies can lead to practical ideas for improving human health. We hope this research will encourage discussions among scientists about applying findings from animal research to develop treatments, ultimately advancing the field of science.

Q: Can you provide an overview of the specific research or activities this grant will support?

Gamble:

Our research involves various assessments, including an eye test to measure ipRGC function, an overnight examination of how light affects the hormone melatonin, an ambulatory assessment of sleep-wake patterns, and an inpatient sleep study. We plan to engage individuals currently using opioid medications (methadone, buprenorphine, or extended-release naltrexone) for participation. Our target is to include 50 participants in each medication group and 50 in a control group. We will then employ these ipRGC function measurements to assess their predictive value for opioid relapse at 1, 3, and 6 months down the line.

Q: What is the desired outcome hoped to achieve with this grant?

Cropsey:

If our hypotheses are supported, we anticipate our findings will shed light on a fundamental mechanism responsible for sleep disruptions in individuals using opioids for opioid use disorder treatment or pain management. We plan to follow participants on these medications for six months to assess whether ipRGC function can predict relapse, which occurs in about 50% of individuals on opioid treatment medications within six months.

Successfully predicting relapse could lead to innovative screening methods and aid in identifying the most effective maintenance medications. Furthermore, it may open the door to addressing sleep problems with proven behavioral interventions, such as chronotherapy using light and exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or rectifying circadian misalignment through bright light therapy.