When I arrived at Palmer Station this past February, I set about what has become a routine whenever I am fortunate enough to visit and live at the station: an assessment of how climate change has altered the region since my last visit. As I was to depart the station after a month’s stay, and there was much to do to help initiate our team’s chemical ecology research, my time for a climate-change check-up was short.

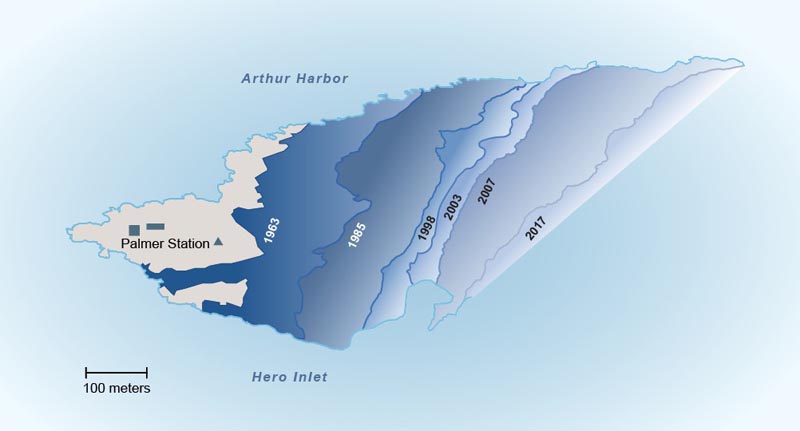

The first thing on my list was to catch up on the state of the Marr Glacier behind the station (the Marr is one of the 87% of the glaciers on the western Antarctic Peninsula currently in retreat). Since our Palmer Station science technician had used GPS to map the leading edge of the glacier as recently as 2017, I had a good idea where the retreating edge lay relative to past decades. In the map below you can see that when Maggie first came down to Palmer Station in 1980, the glacier was almost at the station’s back door. Now you have to hike about a half a kilometer to reach the edge!

To further check-up on the glacier I questioned station residents about the general condition of the glacier over past months. ‘Pock marked with melt holes and coated with crusty ice,’ was a typical response. When queried about the frequency of calving I heard comments like ‘daily thunder,’ or ‘lots of big chunks of falling ice.’ A visual of the action, captured last year by scientist Drew Spacht, is above.

I shared my interest and concern in the rapid retreat of the Marr Glacier with Dr. David Johntson, one of the Principal Investigators with the Palmer LTER (Long Term Ecological Research). David, an expert in the use of drones, proposed that we write a proposal to the NSF (National Science Foundation) to seek support to use drones to map the retreat of the glacier. By flying a series of transects each year, we could use topological software to render in three dimensions the recession of the glacier. We agreed such videos would be exceptional educational outreach tools to inform the public about climate change.

My check-up on climate change at Palmer Station continued with a visit to the birder’s ‘hut,’ a large, canvas tent perched on the back side of the station with a stunning view of the Marr Glacier. Once inside, three of the avian researchers gave me an update on the status of Adelie penguins nesting on the small islands near the station. ‘Not good,’ said Shawn, proceeding to explain that over 100 breeding pairs of Adelies had disappeared just this past year. Shawn explained that this continued a 45-year decline in the local Adelie colonies, now collectively down 90% from the original 15,000 breeding pairs tagged by penguin expert, Bill Fraser, in the mid-1970s.

My Palmer Station climate change check-up concluded with one last hike to the top of the hill behind the station to meet with our science technician Marissa to explore past station weather records. Pouring over monthly measurements of precipitation, she and I agreed that levels of precipitation seem to have been increasing over the years. Unfortunately, it was not possible to separate rainfall from snowfall in the precipitation measurements, but our sense was that it was raining more than it used to at Palmer Station. If this is the case, then Palmer Station is following the general trend of weather changes along the western Peninsula, established in part by the Palmer LTER program. Basically, a climate transitioning from a cold, dry polar environment, to a warmer, more humid, sub-Antarctic environment.

Now, home from my recent month living and working at Palmer Station, my travels continue. Only now they are taking me afar to share this poignant story of climate change and the Palmer Station region with public audiences. It is a sober tale to tell, marked by remarkable changes in both ice and wildlife, and most not for the better. But it is an important story to share, perhaps now more than ever. Our UAB and USF team members know and appreciate that working in such a magnificent, yet fragile, climate-sensitive place carries a responsibility. As scientists, we must share this story of rapid change and the potential loss of biodiversity; for its own sake, and because it foretells changes coming closer to home, changes certain to challenge future generations.