Life at a snail’s pace is anything but slow or boring. My focus since arriving at Palmer Station has been chasing after small to wee tiny snails that live on a very large brown alga easily collected in the subtidal.

Imagine whole wheat lasagna pasta as wide at 20 or more inches across and stretching as much as 40 feet in length or a leather belt of the same dimensions suitable for Paul Bunyan and you would have a good mental image of the brown alga Himantothallus grandifolius (Himanto for short). This massive alga can carpet the seafloor or drape down from underwater cliffs and walls. For additional imagery of our local giant, see this YouTube Chuck filmed a few years ago :

Himanto is home to an impressive array of snails with three of the more abundant species pictured above in paired Noah’s ark-style on a small bit of the alga. The largest, about a US quarter in diameter, are limpets (Nacella concinna). Both limpets appear to be accessorized with pink adornments. Actually, they are providing a home to encrusting red algae growing attached to the limpets shell. The multiple little arms projecting from underneath both limpets are tentacles which help the limpet sense their surroundings for food. The smaller pretty white pearly snails are Margarella antarctica (shorthanded to Marg). Smaller yet is the pair of cone-shaped shells in the center. These tiny snails have a very long name: Eatoniella kerguelenensis regularis. I call it E kerg reg for short. The photo below is what it looks like magnified by a microscope. Pretty cute huh!

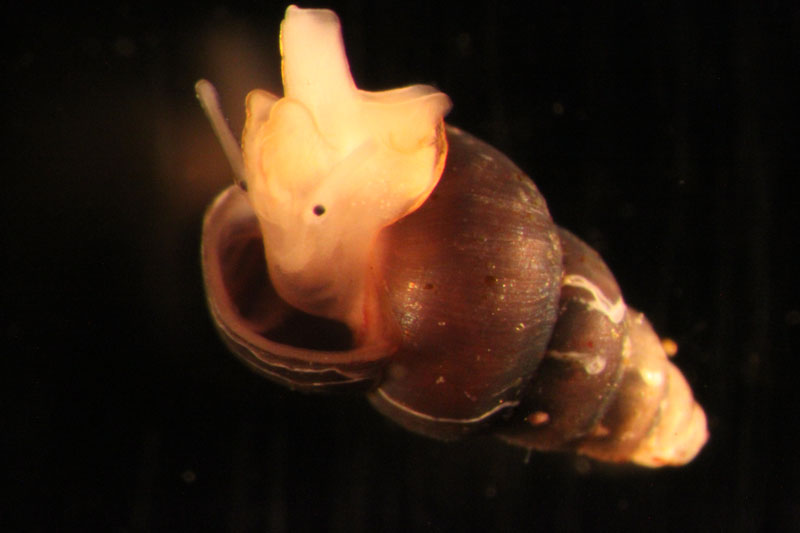

A little taxonomy-speak: E kerg reg, along with the all other snails are collectively known as gastropods. Gastropods are related to bivalves (“two shells” like clams, mussels, oysters) and in turn both are generally known mollusks (aka sea shells). Gastropods differ from other mollusks in that they are anatomically twisted such that the mouth and rest of the digestive tract, along with the foot are both at the same end of the animal. The term dissects into mouth (“gastro”) and foot (“pod”) or mouth-footed. The above image of E kerg reg shows the animal’s two black beady eyes with the mouth in between and broad foot underneath. The twisting or torsion of the gastropod body is in part why snail shells are coiled.

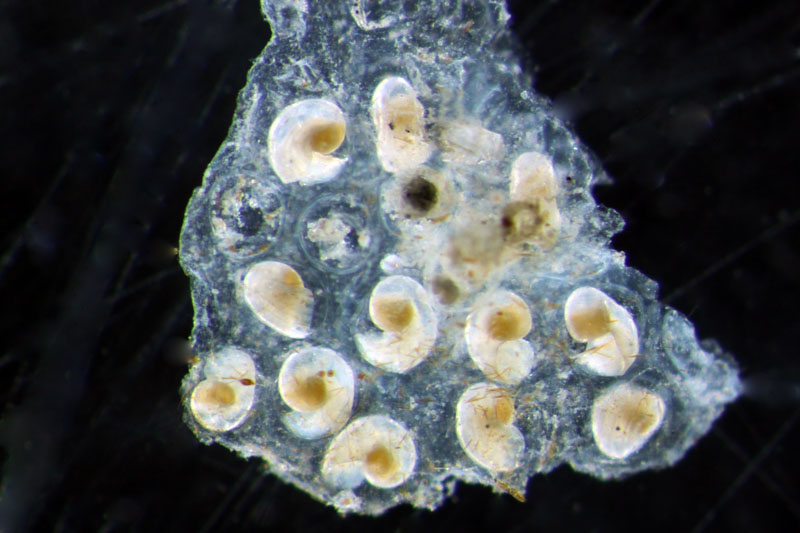

The coil of the gastropod shell and body is easy to see in these practically transparent developing snails. I have also been finding lots similar jelly-like egg masses on Himanto. Hopefully, I can rear the snails to hatching and identify the species.

In addition to the pretty profile of Marg’s coiled shell shown above are three other species of similarly twisted gastropods. On the lower left on the edge of the Himanto is the top ranked abundance-wise Skenella umbilicata. I have yet to get a good picture of this wee tiny snail resembling, on magnification, a spinning top toy. Above Skenella is another minute dark shell shaped like a pyramid. It is E. cana – relative to Ekerg reg. Finally, my favorite: closest to Marg with a chocolate brown shell and dark antennae is Laevilacunaria antarctica (nicknamed Laevilac).

So why am I devoting huge amounts of time to such small critters?? We are interested in the relationship between gastropods and Himanto. Clearly, some of the gastropods use this alga as a nursery as evidenced the occurrence snail egg masses. Do the snails provide some service for the alga? Himanto’s snails, just like those in your garden, are herbivores and like to feed on tender young foliage. However, Himanto is shoe-leather tough and may be too tough for snail teeth. Hmmm - is a puzzlement. Future posts will address this conundrum. Check back.

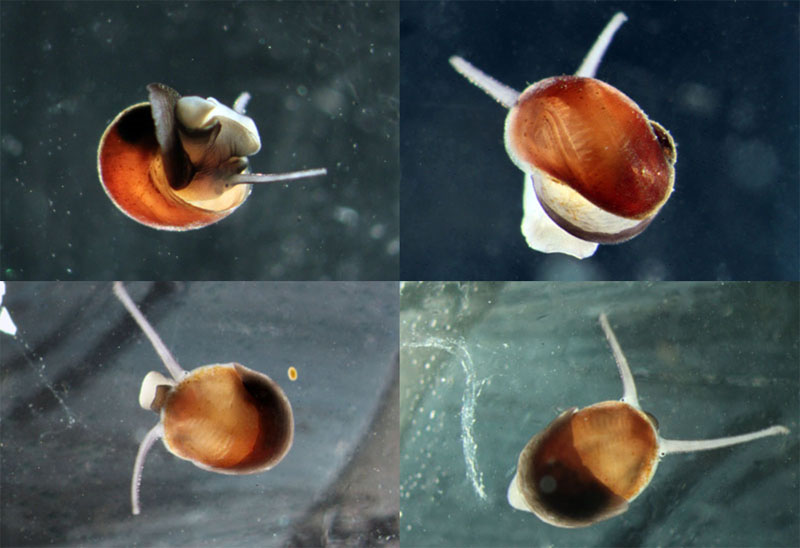

Before you go I want to share pics my favorite snail- Laevilac. The composite above shows various views this little snail. The upper left is a view of the animal with its purplish antennae, black eye, grayish foot and purplish tissue called the mantle. The mantle is partly responsible for making the animal’s shell. One reason La evilac is my favorite is that it can pull its mantle up over the shell, as if attempting to disguise or cloak itself. The upper right image shows Laevilac preparing to ‘cloak.’ The lower pair of images both show a cloaked snail. A little green jelly bean in the lower left is Laevilac’s -excuse me - poop – deposited from an opening very close to the mouth courtesy of the evolution of torsion in gastropods. And evident in the lower right corner, just like your common garden snail, Laevilac leaves a slime trail. Gliding away on slime at a snail’s pace is too quick for this microscoped photographer to keep up. Time for me to run and chase more gastropods. Expect future tales of twisted snails.