A man boarded an airplane in Atlanta in 2007 with a highly contagious, potentially fatal disease that easily can be spread from one person to another.

|

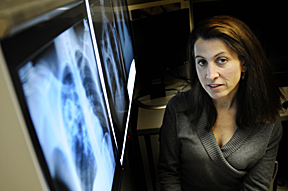

| Think TB is a harmless disease from the past? Elizabeth Turnipseed says to think again. TB is not a half-a-world-away issue. In reality, it’s a cough or sneeze away. |

Think this couldn’t happen a second time? Think again.

This past January a passenger with TB was detained in San Francisco after flying from Philadelphia despite being on a “do-not-board” list.

This is the doomsday scenario government health officials fear when it comes to TB — a disease largely treatable and under control in the United States, but spiraling out of control in other parts of the world. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) 2009 TB report estimates 9.27 million people were diagnosed with the disease worldwide in 2007 with an estimated 1.7 million deaths — numbers that local experts say are conservative estimates.

At the heart of the TB issue is way the virus has replicated to create several different types of TB. There is standard TB, multi-drug resistant TB (MDR TB), extremely drug resistant TB (XDR TB) and another extreme form of TB, known unofficially as XXDR TB, or totally drug resistant TB. The concern of U.S. health officials, says Elizabeth Turnipseed, M.D., voluntary assistant clinical professor and director, disease control for the Jefferson County Department of Health, is that if this extreme form of the disease doesn’t come under control soon in places like Africa and Asia, it could spread to the United States and cause a nightmare health-care scenario.

“People think of TB as an historical disease or somebody else’s problem,” she says. “They think it’s half a world away. In reality it’s just a cough or sneeze away.”

What is TB?

Nancy Dunlap, M.D., professor of medicine in Pulmonary, Allergy & Critical Care, has treated MDR TB patients at UAB in the past, and for 10 years she was a consultant through the Alabama Department of Public Health to patients confined to the maximum-security Kilby Correctional Facility in Montgomery who refused to take their medication properly.

Dunlap says the TB organism is very difficult to treat. Patients must maintain a strict medical regimen of multiple antibiotics for long periods or the disease will progress. The reason: TB differs from common bacteria. It has a very thick, waxy coat, is slow growing and it does not respond to usual antibiotics. If antibiotics are taken improperly, the TB organism may become resistant to them.

“With most bacteria, like pneumonia for example, you get infected and the bacteria divides every 20 minutes, and you’re sick eight hours later,” Dunlap says. “TB divides every day or two. It’s a very slowly progressing, indolent kind of infection.”

Most people with a normal immune system can develop an effective immunity to the TB organism in six to eight weeks. The body effectively walls off the disease and encapsulates it.

“The germ itself may not be dead, but it is contained,” Dunlap says, “and 90 percent of people who have TB bacteria won’t get sick. It’s the other 10 percent who have a tough time with the disease.”

That’s the reason the disease is prevalent in parts of Asia and Africa, where HIV rates are linked to increased diagnoses of XDR TB.

“TB is the leading killer worldwide of people with HIV, and it’s the leading infectious killer of healthy young adults. The burden of disease is just tremendous,” says Turnipseed.

Many people in these developing countries dying with TB have XDR TB, which is resistant to all first- and many second-line drugs. MDR and XDR can develop if medications to treat basic TB aren’t available — the case in most developing countries — or aren’t taken properly by the patient.

History of TB

A 19-year-old Peruvian visiting the United States to study English instead found himself in A.G. Holley State Hospital just south of West Palm Beach in Florida in late 2007. The hospital is the nation’s last standing TB sanatorium and is a quarantine hospital. The student, Oswaldo Juarez, was diagnosed with XXDR TB — a strain that previously had never been seen in the United States and is so rare that only a small number of people in the world are thought to have had it.

Juarez’s diagnosis and treatment — reported for the first time by the Associated Press this past December — caught the attention of Dunlap and Turnipseed.

Dunlap says the fact that the disease in this XXDR form was in the United States is “scary.”

“We have porous borders, and people come and go into our country all of the time,” Turnipseed says, “and we don’t always know who’s coming, who’s going, where they come from or what their issues are. As long as that’s the case, whatever is happening in the world is a potential problem for us.”

Treating TB in the United States

Despite the threat of TB, the good news is that the nearly 20,000 cases of active TB that occur in the United States every year are treatable. The standard of care is a Directly Observed Treatment Shortcourse (DOTS) that involves at least a six-month antibiotic regimen.

“There is a good side to this, and that is that if we do the right things, TB is an imminently treatable disease,” Turnipseed says. “If we can continue to figure out how to develop better diagnostics, make meds available and coordinate resources all over the world so there can be directly observed therapy, that would be even better. Those would be huge steps toward preventing this from becoming a catastrophic problem here at home.”