UAB Researchers Targeting New Ways to Define, Treat the Disease

By Matt Windsor

On September 12, 2008, bestselling author David Foster Wallace, whose 1996 novel Infinite Jest was considered one of the great works of the late 20th century, hanged himself in his California home. Wallace’s father told the New York Times that the 46-year-old writer had been severely depressed for a number of months. For 20 years, Wallace had been taking medication to control his depression, which had allowed him to be productive, his father said. But side effects had led him to wean himself from the medication in June 2007. The depression returned, and after trying several other treatments, including electroconvulsive therapy, Wallace resumed taking his initial medication, only to find that it was no longer effective. “He just couldn’t stand it anymore,” his father told the Times.

(Story continues beneath the video)

We tend to think of America as Prozac Nation—the title of another famous work of the 1990s by Elizabeth Wurtzel. But for every Wurtzel, who wrote about the transformative power of antidepressant medication, there is a Wallace, whose relationship with his treatments was much more difficult.

The Many Degrees of Depression

“The world divides between people who have good response to antidepressant medications and those who do not,” says Richard Shelton, M.D., professor and vice chair of research in the UAB Department of Psychiatry. “Roughly 70 percent of depressed people don’t have adequate responses to SSRIs and SNRIs”—that is, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, which are the first line of treatment for depression.

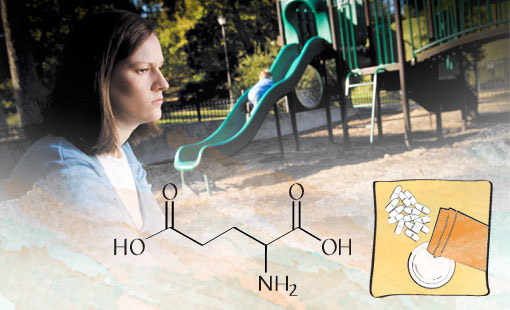

Depression FightersAntidepressant therapy is currently dominated by two related classes of drugs— SSRIs and SNRIs. But these medicines simply don’t work for many patients. UAB researchers are studying several new options. Rapid mood-boosters: Recent research shows that scopolamine (used in motion sickness patches, among other uses) and ketamine (an anesthetic) can raise mood dramatically within a few hours. Administered intravenously in a clinical setting, they could help patients as they wait for slower-acting drugs in pill form to have an effect. Long-term therapy: Unlike SSRIs and SNRIs, which affect serotonin and norepinephrine, new drugs coming on the market target another neurotransmitter called glutamate. These drugs could potentially help many patients who have failed to respond to current medicines. |

The numbers are even worse in terms of long-term response to treatment, as Shelton helped demonstrate in the largest mental health treatment study in history, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR-D) study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

“We found that if you gave a standard antidepressant medication to a group of people with depression, only one in three would actually recover,” Shelton says. Patients do sometimes have a better response to another medicine in the same class, but not nearly as often as doctors’ prescribing habits would suggest, Shelton adds. “What we see in practice is that doctors will just continue to prescribe yet another SSRI, and another one, and another, even though there’s pretty good evidence that if you didn’t have an adequate response, you’re unlikely to respond to the next one in the sequence.”

Why do antidepressants fail so miserably for some patients, when others respond so well? That’s the question that Shelton has been pondering throughout his career. As the director of UAB’s new Mood Disorders Program, he has made it his mission to find enhanced treatments for depression. That starts with the realization that the disease comes in many forms—each of which may require a different treatment option, Shelton says.

“Saying ‘depression’ is like saying ‘cancer,’” he says. “We’re talking about a broad category that is very likely to include multiple subcategories. And I think most doctors are not familiar with that idea. We may even need to change the names of the condition eventually. We don’t call breast cancer just ‘cancer.’ We really need to break apart the syndrome in the same way that oncologists have done.”