Exploring UAB's Past Lives

By Roger Shuler

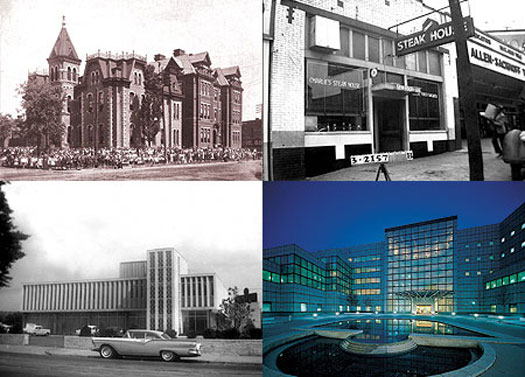

LIFE ON THE BLOCK: A century of change on the site of the Kirklin Clinic (bottom right), one of UAB's signature settings. The block was once home to Hayne Grammar School (top left), then to a series of restaurants and other businesses (top right), and eventually to a savings and loan (bottom left).

LIFE ON THE BLOCK: A century of change on the site of the Kirklin Clinic (bottom right), one of UAB's signature settings. The block was once home to Hayne Grammar School (top left), then to a series of restaurants and other businesses (top right), and eventually to a savings and loan (bottom left).

Like any healthy city, Birmingham is filled with ghosts. Walk through its streets, and behind every emblem of economic vitality—glossy new shopping areas and sleek condo towers—you may be able to detect the outlines of other buildings and older days.

This spectral quality is especially strong in Birmingham's Southside, where more than 80 blocks of homes, businesses, and civic buildings have been transformed into the classrooms, labs, and hospitals of UAB.

| Web Extras: |

One of his favorites is Dr. Gus's BBQ Restaurant. "It was about a block from University Hospital, and it was a popular barbecue joint," Pennycuff says. "I'm sure a lot of people who have been around Birmingham awhile remember Dr. Gus's." The building was on the corner of 18th Street and 7th Avenue South, where the Sparks Center now resides.

What became of this bastion of Birmingham barbecue? A 1958 urban-renewal plan, the first of two such projects that would spur the growth of UAB, sealed Dr. Gus's fate. Its block was swallowed up by the university's westward growth, and the restaurant building was renovated to become the University Hospital School of Nursing.

"I've often wondered if the first group of nursing students could still smell the barbecue," Pennycuff says.

Visions of the Past

UAB Archives holds a treasure trove of historical photographs that illustrate the transformation that has taken place on the Southside. UAB's origins date to September 14, 1936, when the University of Alabama, using a grant from President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, opened its Birmingham Extension Center in an old house downtown at 2131 6th Avenue North.

But the seeds of what would become UAB on Southside were not planted until 1945. That's when the University of Alabama located its new four-year medical school in Birmingham. Jefferson County entered into a contract with the university for the use of Jefferson and Hillman hospitals and conveyed four city blocks (18th to 20th streets and 6th to 8th avenues) that would house the burgeoning medical center—and eventually, UAB, which officially became an independent campus of the University of Alabama system in 1969.

An aerial photo from the 1930s, looking west from what is now the Kirklin Clinic parking lot, shows what the area looked like in the years before the medical center began to take shape. "You had some two-story Victorian homes, plus a number of businesses," Pennycuff says. "There were corner markets and gas stations and pharmacies. I don't think the homes were residential at this point, but they had been. And you notice outbuildings in the alleys.

"As you look west, to where Spain-Wallace and the Eye Foundation Hospital are now located, you can see the rooflines of houses. And there were lots of trees, which I'm sure provided very useful shade in the 1930s, when most places were not air conditioned."

Urban Renaissance

The 1958 urban-renewal project allowed the university to obtain 10½ blocks for expansion, leading to the construction of Lister Hill Library, the School of Optometry, and the School of Nursing. A photo from this period shows a series of apartments on what is now the corner of 20th Street and University Boulevard, the current home of the DoubleTree hotel. "The apartments were built in the early 20th century, and they were purchased by the university and renovated to serve as dorms and apartments in the 1940s and '50s," Pennycuff says. "As residents moved out, they were used for university offices. In fact, the university's first public-relations office was in those apartments."

One photo, looking up 20th Street from the apartments, shows a mansion on the hill where Southern Research Institute now stands. While some opulent homes like this one once framed the southern borders of the medical center, low-income homes were directly to the west. "These were row houses, and most had no indoor plumbing, and some had no electricity into the 1950s," Pennycuff says. "You can see cracks through the sideboards, and I'm sure it could get very hot and very cold. In some photos, you can see laundry hanging out, with the VA Hospital and Jefferson Tower in the background."

A photo from around 1960 shows another historical oddity—the Medical Center Putt-Putt Course. It was across 20th Street from the School of Dentistry and would give way to the Central Bank Building, now UAB's Administration Building.

Westward Again

In 1970, a new urban-renewal project began fueling UAB's growth to the west. Aerial photos from 1970 and 1971 show a forest of cranes rising over the Southside, with Volker Hall, the School of Nursing, Lister Hill Library, and Cooper Green Hospital all being built. By 1973, the first buildings that would become the academic end of campus—Sterne Library and the Chemistry, Education, and Humanities buildings—were in place, fulfilling the dream of Joseph Volker, D.D.S., Ph.D., UAB's first president, who wanted a comprehensive university for Birmingham.

"All of the non-health classes had been taught in Tidwell Hall, which housed the extension center at the time, or in the Engineering Building, now Cudworth Hall," Pennycuff says. "But with UAB becoming an independent campus in 1969, and the major expansion starting in 1970, you can see Joe Volker's dream coming to fruition."