UAB and the Sidewalk Film Festival

Michele Forman was rushing through the Los Angeles Airport one day in September 2004 when her cell phone rang. She recognized the caller ID and suspected it was good news. She was right.

Forman, a documentary filmmaker and an instructor of the Ethnographic Filmmaking class at UAB, had to be out of town during Birmingham’s annual Sidewalk Moving Picture Festival that year. But one of the event’s founders caught up with her from 1,800 miles away as soon as the awards envelope was opened onstage to let her know that a short documentary by two of her students had won top prize in the competition—against entries from as far away as New York City and the Netherlands.

Every year since, Forman and her students have continued to get exciting news. “Not that I’m like a crazed ‘stage mother’ or anything,” Forman laughs, “but having the Sidewalk Festival venue in town has given my students’ productions a whole new level of seriousness. It’s one thing if your teacher and classmates are the only ones who see your work, but seeing it on a big screen, and getting to experience a live crowd’s reaction at a public screening, is just electrifying, for them and for me. I like to say that it ‘completes the educational circuit’ and connects them to the larger community.”

Big Ideas in Five Minutes

Competitions aside, the goal of students in Forman’s interdisciplinary class is to learn ethnographic and documentary filmmaking. In the process, they use film and video to document aspects of human social life through a method that’s sometimes called “guerrilla filmmaking”—because the two-person production teams tend to use a minimum of equipment and try not to alter or intrude on the situations they’re documenting.

Another limitation on assignments is the fact that “short documentary” means exactly that; five minutes is the designated screen time for each project—six minutes, tops.

“There’s always some shock when students find out how short their films have to be,” says Forman. “At the beginning they say, ‘But this story is different; I need at least 20 or 30 minutes to tell it.’ The learning process, though, is about compressing a story, boiling it down to its essence. That’s what gives a work its impact.

“It’s agonizing, but at the end they’re both exhausted and relieved that they’ve distilled so much material into a core story; they find themselves at a new level of intellectual and emotional maturity when they finish. It’s very satisfying for me, and very moving, to see students grappling with big themes and major ideas.”

Since human social life is such a broad category, to say that the class usually tackles an eclectic range of topics would be an understatement. Past subjects have included hip-hop musicians, a faith-based ghost-hunting club, belly dancers, a clown troupe, a Sikh religious community, aficionados of railroad-car graffiti, film enthusiasts who saved and restored a dying movie house, the people who ride urban transit, and a body-piercing parlor, to name but a few.

Since human social life is such a broad category, to say that the class usually tackles an eclectic range of topics would be an understatement. Past subjects have included hip-hop musicians, a faith-based ghost-hunting club, belly dancers, a clown troupe, a Sikh religious community, aficionados of railroad-car graffiti, film enthusiasts who saved and restored a dying movie house, the people who ride urban transit, and a body-piercing parlor, to name but a few.

From Reel to Real

The student filmmakers’ own backgrounds are a diverse mix as well—from the humanities to science, medicine, and education. “We’ve had a number of education students who’re now using their multimedia skills in their classrooms,” says Forman. “In fact, the skills they learn in filmmaking—such as listening well, and explaining complex information in an understandable way—are useful in any job, from the business world to academics, as well as in just being a good citizen.”

One student received a prestigious Fulbright Fellowship and used the funding to document a community of midwives in British Columbia. Another student has gone into filmmaking full-time and is rising through the ranks at a local production company.

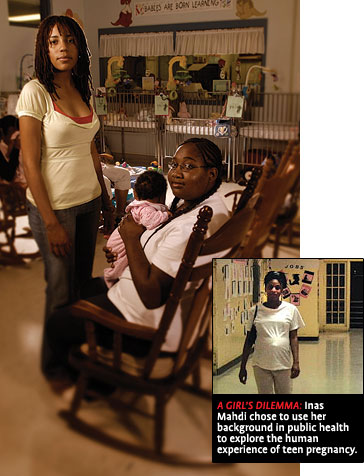

Inas Mahdi, a graduate student in public health, brought her career skills to bear on her documentary about a program for pregnant high schoolers. “My background is in HIV and teen pregnancy prevention,” Mahdi says, “and I wanted to fuse my scientific side and my artistic side to tell a story about the human experience of being young and pregnant.

“The community connections were more than we could have hoped for—we built relationships with grandmothers, teenagers, parents, teachers, principals, and caregivers. It’s an experience we’ll take with us wherever we go.” Mahdi’s film, A Girl’s Dilemma, apparently connected with audiences, as well. After it screened, she was approached by a group of people who commissioned her to produce another documentary, this one about a spiritual retreat for HIV-positive people and their caregivers and health-care providers.

Fluid Focus, Blinders Off

Clay Daniels is another student whose project drew more response than he anticipated. A biology major, Daniels took the class to pursue something “completely unrelated” during his last semester before grad school: “I had heard a church pastor speak at different gatherings on campus about conflicts between Christianity and gay rights, and I was intrigued by how his congregation resolved those problems.”

He says his approach to the project took several unexpected turns during research and production: “Being more of an agnostic than a follower of any faith myself, I found it difficult to relate to the spirituality of the people I was featuring,” Daniels says. “But I completely understood their need to be accepted as openly gay persons in all aspects of their lives. So the focus of the film changed; instead of being mainly about how members of the congregation resolved the conflict, it became more about why the reconciliation of religion and sexuality is so necessary.

“The main thing I learned from the class is not to let your preconceived ideas blind you to the truth that a subject, itself, presents. That’s a lesson I’ll use while studying biological systems here at UAB.”

Daniels’s film, Congregation, was chosen as a finalist to screen at theSidewalk competition downtown; it was also picked for the annual “Sidewalk Sneak” preview at the Alys Stephens Center. In addition, it was accepted into the Fresno Reel Pride Gay and Lesbian Film Festival in California and will be screening at the first annual Birmingham SHOUT: Gay + Lesbian Film Festival of Alabama.

Zandile Moyo likewise found her short documentary, Beneath These Hills—another Sidewalk finalist—evolving while she worked on it. Though she was initially drawn to the architectural styles of the houses and commissary in the historic coal-mining town of Docena on the outskirts of Birmingham, her focus gradually shifted to the dramatic stories of the people who lived there.

“They had explosions in the mines,” one of her interview subjects, an elderly man, says onscreen in a dramatic close-up. “I was down there during one of ’em, but it didn’t get me. It killed 30 or 40 people. A lady come down there hollerin’, ‘Lord, my husband! I know he’s gone. . . .’”

“People don’t tend to think of Birmingham as a place where a lot of interesting things are happening,” Moyo says, “but we found out what an untapped source it is for great documentaries. I’ve taken film classes in New York City and San Francisco, but I’ve never had one as thorough as Michele’s. I think she is the main reason UAB continues to have such a strong presence at the Sidewalk Festival.”