Emily Dolan1, 2, Cassandra Newsom2, Melissa Smith3, Rushambli Patel1, Maureen Lichtveld4, Wilco Zijlmans5, Hannah Covert4, Ashna Hindori-Mohangoo6, Anisma Gokoel7, Jeffrey Wickliffe8

1Undergraduate Neuroscience Program; 2Civitan Autism and Neurodevelopment Research Core; 3Department of Biostatistics; 4Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 5Faculty of Medical Sciences, Anton de Kom University, Paramaribo, Suriname; 6Perisur, Paramaribo, Suriname; 7Academic Hospital Paramaribo; 8Department of Environmental Health Sciences

Abstract

It is imperative to investigate potential risk factors associated with the increased appearance of neurodevelopment-related diagnoses and delays in children. Toxic exposure to lead and mercury has been shown to have significant correlations with impaired neurodevelopment. This study aims to examine if prenatal exposure to these metals in Suriname affects aspects of neurodevelopment and if this exposure varies by region.

The Caribbean Consortium for Research in Environmental and Occupational Health (CCREOH) collected data from 708 mother-child dyads. In the first and second trimesters, blood samples were collected from the mothers to examine levels of lead and mercury exposure. At 2-3 years of age, their children were assessed using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Version III (BSID-III) to determine their stage of language, motor, and cognitive development.

First, Spearman’s correlation was used to compare the mother's level of lead and mercury exposure to their child's BSID-III scores. Second, an ANCOVA analysis was used to compare each mother's exposure to lead and mercury, as well as their child's score on the BSID-III, across different regions of Suriname.

This study's findings can provide key insights into heavy metal exposure. First, how different types of metal exposure can be associated with characteristic delays in neurodevelopment. Second, how one's location can leave them vulnerable to various forms of exposure, with these findings, interventions to reduce one's risk of exposure could be studied and implemented.

Introduction

There has been a steady increase in the appearance of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) such as Autism, which are characterized by a delay in typical markers of development, such as language, motor skills, or cognitive abilities1,2. It is imperative to examine potential risk factors for developing an NDD3. While there has been much research on biological contributors, such as genetic predispositions, infections experienced during pregnancy, and medications taken during pregnancy4, further work needs to be conducted on environmental risk factors, such as exposure to heavy metals.

A heavy metal causes harm either through excess exposure or by interfering with integral physiological processes5. Heavy metal exposure can occur through consumption, inhalation, and application of cosmetic products1. During critical periods of development, such as pregnancy and early childhood, exposure to heavy metals can be especially harmful1. Past literature has established that lead (Pb) has no safe level of exposure and adverse effects on neurodevelopment, such as impaired cognitive development, conduct problems, and hyperactivity, and decreased release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)6,7. While mercury (Hg) has been classified as harmful, its role in neurodevelopment has been limited and inconclusive7. In past studies, limited direct negative relationships have been found, and they have been speculated to be mitigated by factors such as folate and fish consumption8,9.

Due to limited resources in managing environmental toxicants, past studies have found that low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are particularly vulnerable to the harms of heavy metal exposure due to limited resources to monitor use and reduce exposure6. Suriname, as an upper-middle-income country, experiences a wide array of adverse birth outcomes, such as stillbirth, maternal mortality, and preterm birth10. Due to their economic practices of rice cultivation and gold mining, Surinamese individuals are particularly vulnerable to lead and mercury exposure11. Despite a widespread vulnerability to adverse birth outcomes and environmental exposure, Suriname as a country is very diverse in terms of its inhabitants and their unique risks of exposure, which calls for it to be divided into three regions for this study: Coastal, Agricultural, and Interior.

The Coastal region consists of the districts Paramaribo, Wanica, Commewijne, Saramacca, and Para, which are nestled near the coast of Suriname. These districts have a larger urban population of citizens with higher socioeconomic status (SES), comprising nearly two-thirds of the Surinamese population11. The Agricultural region consists of the districts Nickerie and Coronie, where its main agricultural export of rice is produced13. The Interior region consists of Marowijne, Brokopondo, and Sipaliwini, which are inhabited by indigenous populations and house gold mining operations11, 13. Suriname, a country vulnerable to lead and mercury exposure with a diverse population, presents an opportune setting to investigate the associations between lead and mercury exposure and NDDs11, 13.

This study aims to understand how prenatal exposures to lead and mercury are associated with NDDs as characterized by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Version III (BSID-III), and how exposure and BSID-III subscores vary by region. This study hypothesizes that both lead and mercury will have negative impacts on all BSID-III subscores and that the Interior region will experience the highest exposures and lowest BSID-III subscores due to their proximity to gold-mining operations.

Method

Procedure

Human Subjects Protection authorities approved the CCREOH study at all participating institutions, as well as the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, Medical Ethical Committee of the Ministry of Health in Suriname (reference number VG 023-14), and the Institutional Review Board of Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA (study number 839093). All collected information has since been deidentified.

Blood samples were taken from mothers in their late first to early second trimester, and heavy metal concentrations were recorded in ug dL-1. After the subsequent birth of their children and a two to three-year waiting period, the children were evaluated utilizing the BSID-III, a standard measure of infant and child development validated for use in Suriname12.

Materials

The BSID-III is a tool used to identify developmental delays for children from 16 days old to 42 months old14. It consists of Expressive Communication (EC), Receptive Communication (RC), Gross Motor (GM), Fine Motor (FM), and Cognitive (COG) scales14 Lower subscores on this assessment indicate developmental concerns14.

Participants

The CCREOH collected data from 708 mother-child dyads. To be included in this study, mothers had to have complete blood data for exposure to lead and mercury in the first or second trimester, demographic data (Ethnicity, Education, SES, Age, Region), and their children had to have a validated BSID-III assessment. Participants resided in the Coastal (406, 57.3%), Agricultural (168, 23.7%), and Interior (134, 18.9%) regions of Suriname, and they had an overall mean age of 28 (SD =6.3) with a range of 15 to 48. Demographic information on maternal ethnicity, SES, education, and age as well as mean heavy metal exposure and BSID-III subscale subscores are pictured in Table 1a and 1b.

Table 1a

| Participants | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Overall 708 (100) | Coastal 406 (57.3) | Agricultural 168 (23.7) | Interior 134 (18.9) |

| Ethnicity | African Descent 274 (38.7) Asian Descent 199 (28.1) Other 235 (33.2) |

African Descent 196 (48.3) Asian Descent 97 (23.9) Other 64 (15.8) |

African Descent 14 (8.3) Asian Descent 101 (60.11) Other 53 (31.5) |

African Descent 64 (47.8) Asian Descent 1 (0.7) Other 69 (51.5) |

| Education | None or Primary 159 (22.5) Secondary 435 (61.4) Tertiary 114 (16.1) |

None or Primary 44 (10.8) Secondary 268 (66) Tertiary 94 (23.2) |

None or Primary 13 (7.7) Secondary 136 (81) Tertiary 19 (11.3) |

None or Primary 102 (76.1) Secondary 31 (23.1) Tertiary 1 (7.5) |

| SES (SRD) | <3000 470 (66.4) 3000-4999 158 (22.3) 5000+ 80 (11.3) |

<3000 233 (57.4) 3000-4999 108 (26.6) 5000+ 65 (16) |

<3000 113 (67.3) 3000-4999 45 (26.8) 5000+ 10 (6) |

<3000 124 (92.5) 3000-4999 5 (3.7) 5000+ 5 (3.7) |

Table 1b

| Participants | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28 (6.28) | 28.99 (6.24) | 26.76 (5.57) | 26.58 (6.71) |

| Exposure (ug dL-1) | Pb 3.22 (3.79) Hg 6.14 (8.76) |

Pb 1.65 (1.83) Hg 2.64 (2.82) |

Pb 1.71 (1.77) Hg 2.25 (1.91) |

Pb 6.54 (2.07) Hg 13.2 (2.29) |

| BSID-III Subscale | EC 9.05 (2.41) RC 9.3 (2.45) GM 10.36 (3.3) FM 10.87 (2.5) COG 11.39 (2.94) |

EC 9.29 (2.19) RC 9.26 (2.23) GM 10.33 (2.86) FM 10.74 (2.44) COG 10.85 (2.67) |

EC 9.35 (3.1) RC 9.89 (2.91) GM 11.5 (3.77) FM 11.23 (2.56) COG 13.07 (3.0) |

EC 7.97 (1.65) RC 8.67 (2.27) GM 9.03 (3.4) FM 10.84 (2.58) COG 10.93 (2.88) |

Data Analysis

The first round of analysis explored whether prenatal exposure to lead and mercury impacted BSID-III subscores. A Spearman correlation was used via SPSS to find significant relationships between BSID-III subscores and natural log-transformed lead and mercury concentrations, due to the non-normal distribution of the heavy metal data. Next, a Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing (LOESS) Line was used to picture significant relationships on a scatterplot.

The second round of analysis investigated whether the mother’s region impacted heavy metal exposure and BSID-III subscores. A series of chi-square tests and an ANOVA was used to determine if there were significant differences in demographic information across the three regions of Suriname. Next, an ANCOVA was run to investigate regional differences in natural log-transformed lead and mercury concentrations and BSID-III subscores while controlling demographic factors.

Results

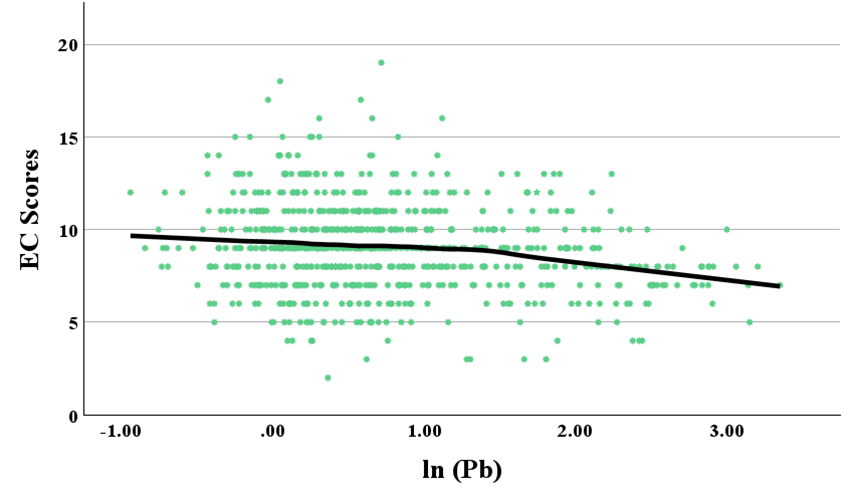

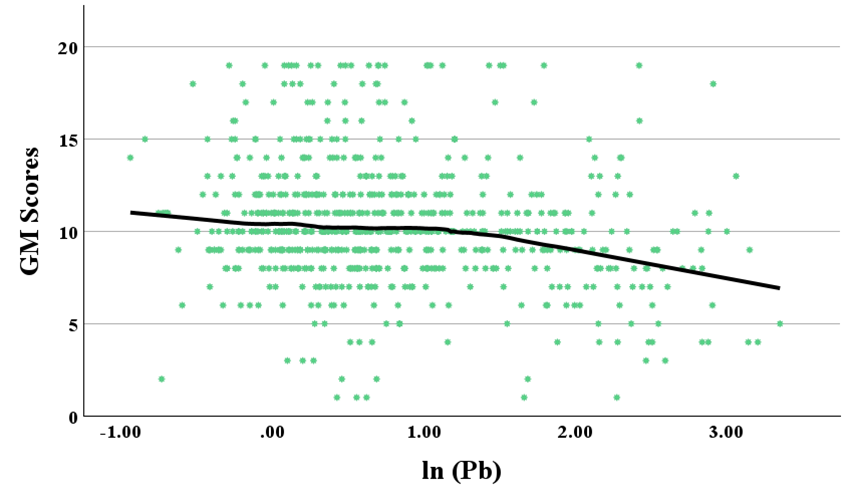

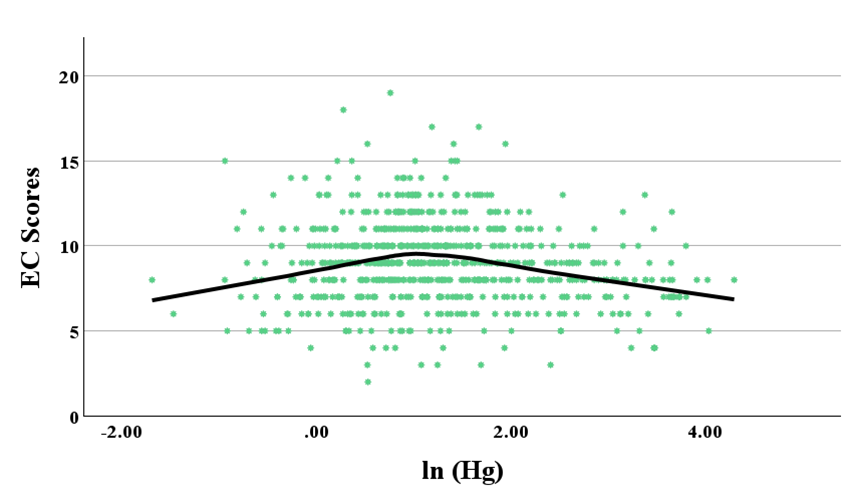

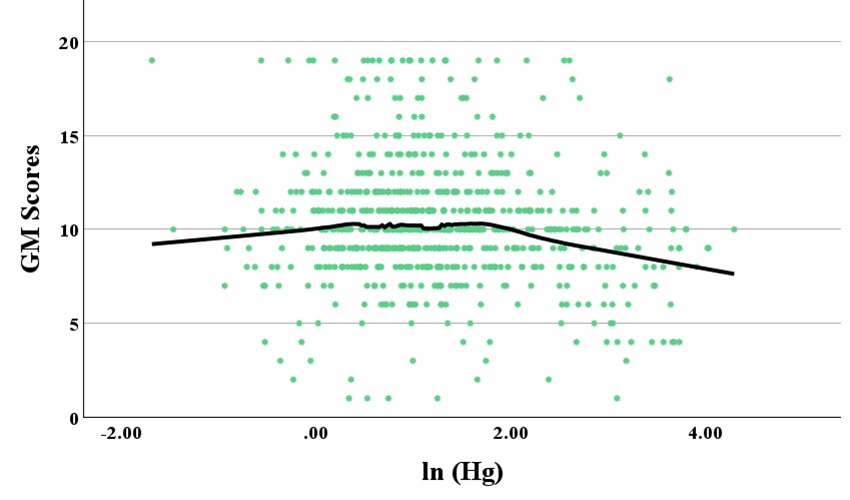

A Spearman's correlation was used to evaluate the relationship between the prenatal lead and mercury exposure and subsequent subscores on the BSID-III (Table 2). There was a significant negative relationship found between prenatal lead exposure and all BSID-III subscores, the strongest two being EC (ρ = -0.18, p = < 0.001, N = 708) and GM (ρ = -0.17, p = < 0.001, N = 708). There was also a significant negative relationship found between prenatal mercury exposure and the EC, RC, and GM subscores, with the strongest two also being EC (ρ = -0.08, p = 0.026, N = 708) and GM (ρ = -0.1, p = 0.007, N = 708). A LOESS line was used to depict all significant relationships. Increasing lead exposure correlates with decreasing EC and GM scores (Figure 1a and 1b). EC and GM scores appear to increase then decrease as mercury exposure increases, indicating that the negative Spearman correlation may be masking a non-monotonic relationship (Figure 2a and 2b).

Table 2

| Metal | BSID-III Scale | ρ |

|---|---|---|

| Ln (Pb) | EC | -0.18*** |

| Ln (Pb) | RC | -0.13*** |

| Ln (Pb) | GM | -0.17*** |

| Ln (Pb) | FM | -0.08 * |

| Ln (Pb) | COG | -0.09* |

| Ln (Hg) | EC | -0.08* |

| Ln (Hg) | RC | -0.07* |

| Ln (Hg) | GM | -0.1** |

| Ln (Hg) | FM | 0.02 |

| Ln (Hg) | COG | -0.04 |

*p < .05, **p< 0.01, ***p < .001 (two-tailed)

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Image Descriptions (Figures 1a and 1b): Scatterplots of the natural logarithm of lead against Gross Motor (GM) and Expressive Communication (EC) scores. Both graphs focus on lead exposure ln (Pb) as the independent variable, with Figure 1a illustrating a negative association with EC scores and Figure 1b with GM scores.

Figure 2A

Figure 2B

Image descriptions (Figures 2a and 2b): Scatterplots of the natural logarithm of mercury against Gross Motor (GM) and Expressive Communication (EC) scores. Both graphs focus on mercury exposure ln (Hg) as the independent variable, with Figure 2a illustrating a non-monotonic relationship with EC scores and Figure 2b with GM scores.

A series of chi-square tests of independence found significant group differences by region in maternal ethnicity, SES, education (Table 3a & 3b). A one-way ANOVA found significant group differences in maternal age by region (Table 3a & 3b).

Table 3a

| Tests | (df, N) | χ² | Cramer's V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 4, 708 | 169.17** | 0.35 |

| Education | 4, 708 | 290.79** | 0.45 |

| SES | 4, 708 | 63.37** | 0.21 |

Table 3b

| ANOVA Analysis | (df, N) | F | η² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2, 708 | 12.11** | 0.03 |

*p < .05, **p < .001 (two-tailed)

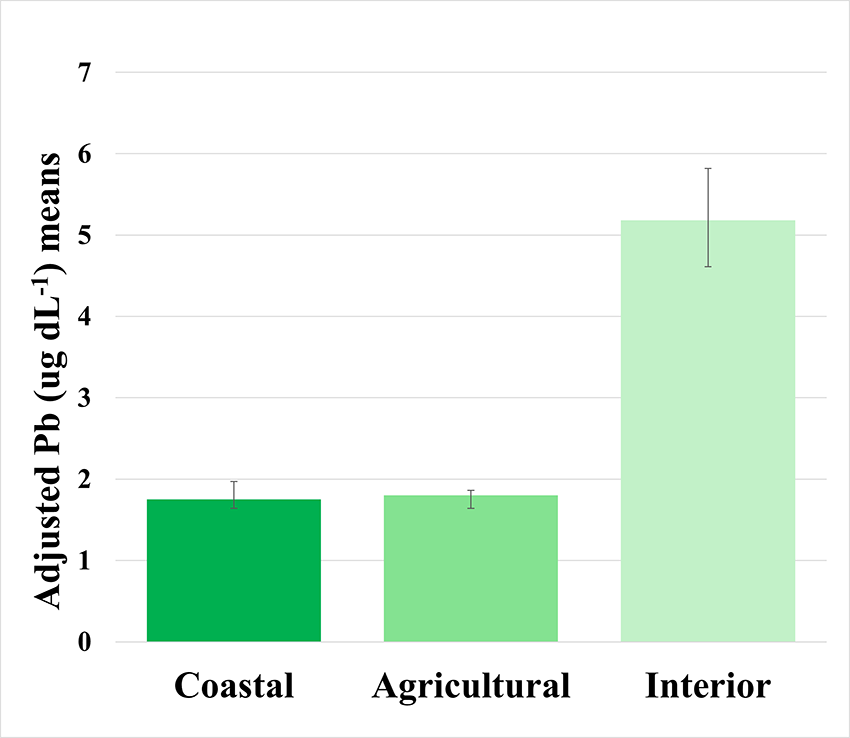

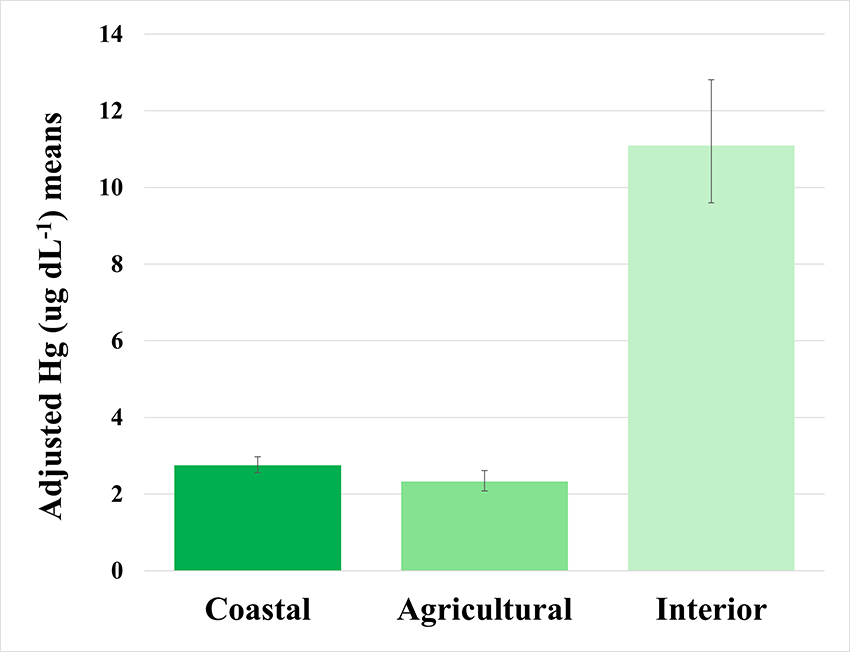

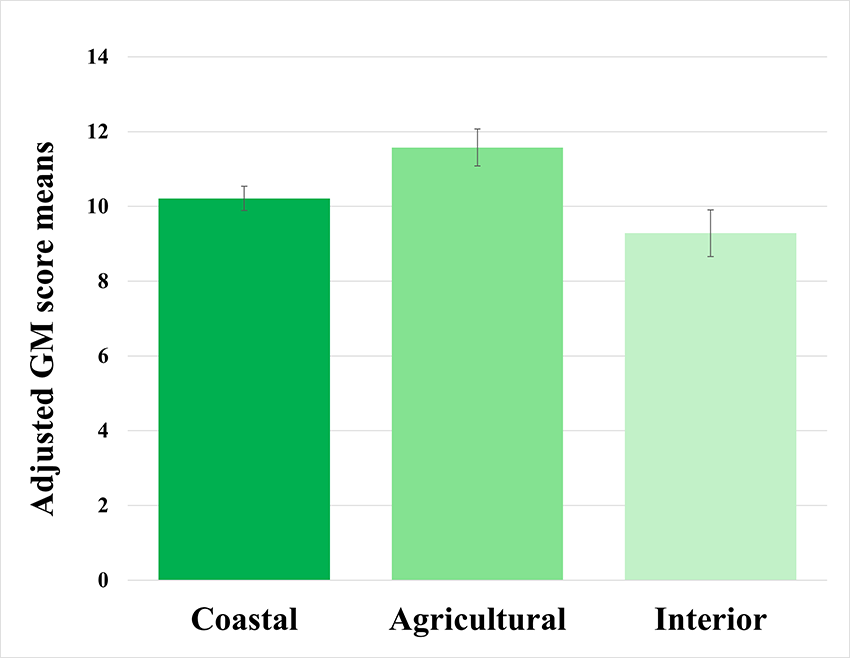

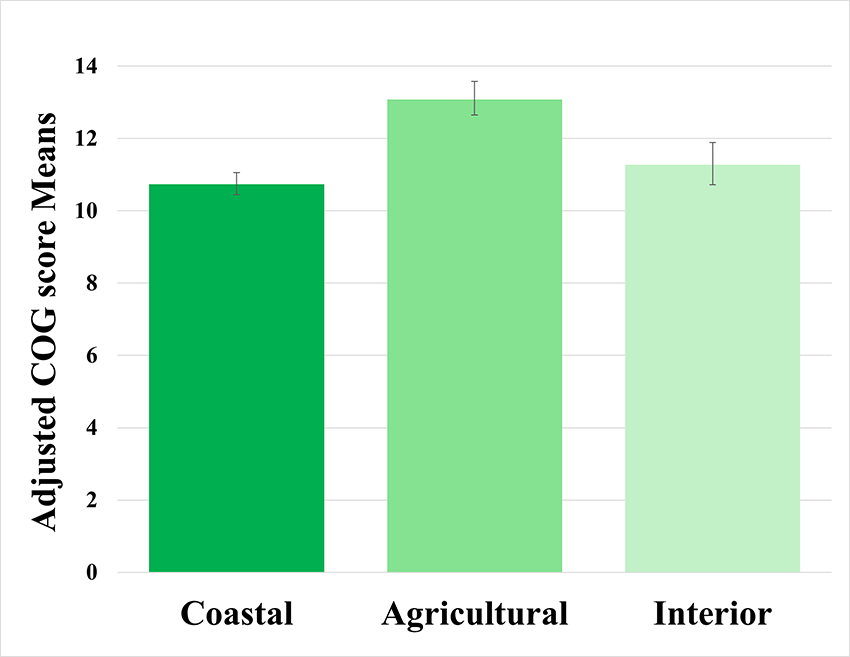

A one-way ANCOVA was conducted to examine the effect of region on prenatal lead and mercury exposure and BSID-III subscores, while controlling maternal ethnicity, SES, education, and age. There was a significant effect of region on both types of exposure and all BSID-III scales, with lead (F(2, 708) = 127.035, p = < .001, partial η² = 0.27 and mercury (F(2, 708) = 153.76, p = < .001, partial η² = .31) having substantial differences compared to the BSID-III subscores (Table 5). Among the BSID-III subscores, the COG (F(2, 708) = 40.33, p = < .001, partial η² = .1) and GM (F(2, 708) = 17.49, p = < .001, partial η² = .1) subscales (Table 4). Bar graphs were utilized to illustrate significant adjusted mean differences (Table 5a and 5b) for lead exposure (Figure 3a), mercury exposure (Figure 3b), Gm scores (Figure 4a), and COG scores (Figure 4b).

Table 4

| Exposure/Subscales | df, N | F | Partial η² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure ln (Pb) | 2, 708 | 127.03*** | 0.27 |

| Exposure ln (Hg) | 2, 708 | 153.76*** | 0.31 |

| BSID-III Subscale EC | 2, 708 | 7.81*** | 0.02 |

| BSID-III Subscale RC | 2, 708 | 6.5** | 0.02 |

| BSID-III Subscale GM | 2, 708 | 17.49*** | 0.05 |

| BSID-III Subscale FM | 2, 708 | 4.4* | 0.01 |

| BSID-III Subscale COG | 2, 708 | 40.33*** | 0.1 |

*p < .05, **p< 0.01, ***p < .001 (two-tailed)

Table 5a

| Region | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Coastal | 406 (57.3) |

| Agricultural | 168 (23.7) |

| Interior | 134 (18.9) |

Table 5b

| Exposure/BSID-III Subscale | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure (ug dL-1) | Pb 1.75 (1.64-1.97) Hg 2.75 (2.56 - 2.97) |

Pb 1.8 (1.64-1.86) Hg 2.33 (2.08-2.61) |

Pb 5.18 (4.61-5.82) 11.09 (9.6-12.81) |

|

| BSID-III Subscale | EC 9.2 (8.96-9.44) RC 9.22 (8.97-9.46) GM 10.21 (9.89-10.54) FM 10.61 (10.36-10.86) COG 10.73 (10.45-11.02) |

EC 9.37 (9.0-9.73) RC 9.87 (9.49-10.25) GM 11.57 (11.075-12.07) FM 11.19 (10.8-11.57) COG 13.08 (12.65-13.51) |

EC 8.22 (7.76-8.68) RC 8.83 (8.35-9.31) GM 9.29 (8.66-9.91) FM 11.28 (10.8-11.77) COG 11.27 (10.72-11.81) |

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

Image Descriptions (Figures 3a and 3b): Box plots comparing prenatal lead and mercury exposure across regions. Plots indicate the Interior region has higher levels of lead (Pb ug dL-1) in Figure 3a and mercury (Hg ug dL-1) exposure in Figure 3b than the Agricultural and Coastal regions. Lead and mercury have been back-transformed from natural logarithms, and error bars are set at 95% CI.

Figure 4a

Figure 4b

Image Descriptions ((Figures 4a and 4b): Figure 4 | Box plots comparing Gross Motor (GM) and Cognitive (COG) scores across regions. Figure 4a demonstrates that the Interior region has the lowest GM scores, while Figure 3a indicates that the Coastal region has the lowest COG scores. Error bars are set at 95% CI.

Discussion

This study examined associations between prenatal heavy metal exposure and BSID-III subscores. Spearman correlations demonstrated significant negative relationships between prenatal lead exposure and all BSID-III scales, and between mercury exposure and the GM and EC scales. However, mercury's negative correlations appear to be non-monotonic, indicating its relationship with the GM and EC subscales may not be accurately reflected by the Spearman correlation, necessitating further analysis (Figures 2a and 2b). This study’s lead hypothesis was consistent with the results, but the mercury hypothesis was not.

The findings were consistent with past literature6. Past work has shown lead exposure to have a consistent adverse effect across multiple domains of development, particularly language15 and motor8 development. Mercury, while having demonstrated negative associations with cognition17, is not consistently shown to have a negative relationship with other markers of development, such as motor skills6, 16. This, in part, has been due to mercury's interaction with other substances, such as folate9, or the adverse effects of mercury being outweighed by the positive effects of fish consumption, particularly in families with limited access to nutrient-dense foods6, 11.

This study also examined if a mother’s region impacted prenatal heavy metal exposure and BSID-III subscores. The ANCOVA demonstrated a significant difference in prenatal exposure to Lead and Mercury across the Interior, Agricultural, and Coastal regions of Suriname (Table 4). The Interior region had the highest level of exposure to lead and mercury (Figure 3a and 3b). Individuals within the Interior are more likely to be exposed to lead and mercury via artisanal-scale gold mining (ASGM) and consumption11. In ASGM, mercury is used and then discarded into the environment, where it can build up in fish, a primary food source for the Interior inhabitants of Suriname11. While the exact source of lead has not been definitively established, there have been reports that manioc, a root vegetable frequently consumed in Suriname, could be a potential source18.

The ANCOVA demonstrated significant differences between each scale of the BSID-III across all regions, accounting for all demographic factors (Table 3). The Interior region had the lowest scores in the EC, RC, and GM scales while the Coastal region had the lowest score on the FM and COG scales (Table 5). The lower scores on the EC, RC, and GM scales in the Interior can be partially attributed to their significantly higher exposure compared to the Coastal and Agricultural regions (Figure 3a and 3b)8, 15. The lower scores on the FM and COG scales in the Coastal region, however, warrant further analysis due to their lower levels of lead and mercury exposure. This finding could indicate that there may be factors at play that were not controlled for, such as the child's sex, the mother's marital status, and the child's access to early educational services and materials, which can be associated with cognitive and motor delays19, 20. The EC, RC, and GM scores were consistent with this study’s hypothesis.

Future Directions

In Suriname, mothers can experience exposure to multiple metals rather than a single metal, which may have interactions that are especially detrimental to fetal neurodevelopment21. It is imperative to explore interactions between lead and mercury, other metals associated with impaired neurodevelopment6, and with protective factors, such as fish consumption11.

Behavioral outcomes should also be investigated. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)22 assesses children's emotional and behavioral capabilities via parent reports, serving as a valuable measure to evaluate how a child's behavior influences their ability to react to new situations and relationships, which will be imperative to investigate neurodevelopmental disorders such as Autism.

Conclusion

This study aimed to find if there were significant relationships between lead and mercury exposure and neurodevelopmental delays in Suriname as indicated by the subtests of the BSID-III. While lead was shown to have a negative correlation with the EC and GM subscales of the BSID-III, mercury's negative correlation will require future investigation. Additionally, this study sought to investigate if a mother’s region contributed to lead and mercury exposure and changes in BSID-III subscores, accounting for demographic factors. From that analysis, the Interior region was shown to have the highest prenatal metal exposure and lower subscores in the EC, RC, and GM scales of the BSID-III. While the Coastal region had lower prenatal metal exposures, they reported lower scores on the FM and COG scales, warranting further analysis.

References

- Villagomez, A. N., et al. Neurodevelopmental delay: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data opens a new website . Vaccine. 37(52), 7623–7641 (2019).

- Witkowska, D., Słowik, J., & Chilicka, K. Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites opens a new website . Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 26(19), 6060 (2021).

- Cainelli, E. & Bisiacchi, P. Neurodevelopmental disorders: past, present, and future opens a new website . Children. 10(1), 31 (2022).

- Amaral D. G. (2017). Examining the Causes of Autism opens a new website . Cerebrum: the Dana forum on brain science, 2017, cer-01-17 (2017).

- Singh, R., Gautam, N., Mishra, A., & Gupta, R. Heavy metals and living systems: an overview opens a new website . Indian J Pharmacol. 43(3), 246-253 (2011).

- Heng, Y. Y., et al. Heavy metals and neurodevelopment of children in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review opens a new website . PLoS ONE. 17(3), 1–25 (2022).

- Parithathvi, A., Choudhari, N., & Dsouza, H. S. Prenatal and early life lead exposure induced neurotoxicity opens a new website . Human & Experimental Toxicology. 43, 1–14 (2024).

- Hu, Y., et al. Prenatal low-level mercury exposure and infant neurodevelopment at 12 months in rural northern China opens a new website . Environmental science and pollution research international, 23(12), 12050–12059 (2016).

- Kim, B., et al. Adverse effects of prenatal mercury exposure on neurodevelopment during the first 3 years of life modified by early growth velocity and prenatal maternal folate level opens a new website . Environmental Research. 191, 109909 (2020).

- Verschueren, K.J.C., et al. Childbirth outcomes and ethnic disparities in Suriname: a nationwide registry-based study in a middle-income country opens a new website . Reprod Health. 17, 62 (2020).

- Abdoel Wahid, F.Z., et al. Geographic differences in exposures to metals and essential elements in pregnant women living in Suriname opens a new website . J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol, 33(6), 911–920 (2023).

- Fleurkens-Peeters, M. J., et al. The United States reference values of the Bayley III motor scale are suitable in Suriname opens a new website . Infant behavior & development. 74, (2024).

- Zijlmans, W., et al. Caribbean Consortium for Research in Environmental and Occupational Health (CCREOH) Cohort Study: influences of complex environmental exposures on maternal and child health in Suriname opens a new website . BMJ open, 10(9), e034702 (2020).

- Balasundaram, P., & Avulakunta, I. D. Bayley Scales Of Infant and Toddler Development opens a new website . In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing (2022).

- Shiani, A., et al. Effect of Exposure to Toxic Compounds on Developmental Language Disorder: A Brief Review opens a new website . Iranian Journal of Toxicology. 19(1), 37–44 (2025).

- Dórea, J. G., Marques, R. C., & Abreu, L. Milestone Achievement and Neurodevelopment of Rural Amazonian Toddlers (12 to 24 Months) with Different Methylmercury and Ethylmercury Exposure opens a new website . Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 77(1–3), 1–13 (2014).

- Rothenberg, S. E., et al. Maternal methylmercury exposure through rice ingestion and child neurodevelopment in the first three years: a prospective cohort study in rural China opens a new website . Environmental health: a global access science source. 20(1), 50 (2021).

- Rimbaud, D., et al. Blood lead levels and risk factors for lead exposure among pregnant women in western French Guiana: the role of manioc consumption opens a new website . Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 80(6), 382-393, 2017.

- Arrhenius, B., et al. Social risk factors for speech, scholastic and coordination disorders: a nationwide register-based study opens a new website . BMC Public Health. 18(1), 739 (2018).

- Veldman, S. L., Jones, R. A., Chandler, P., Robinson, L. E., & Okely, A. D. Prevalence and risk factors of gross motor delay in pre‐schoolers opens a new website . Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health., 56(4), 571–576 (2020).

- Nyanza E. C., et al. Effects of prenatal exposure and co-exposure to metallic or metalloid elements on early infant neurodevelopmental outcomes in areas with small-scale gold mining activities in Northern Tanzania. opens a new website Environ International. 149, 106104 (2021).

- Offermans, J. E., et al. The Development and Validation of a Subscale for the School-Age Child Behavior CheckList to Screen for Autism Spectrum Disorder opens a new website . Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 53(3), 1034–1052 (2023).