Author: Meagan A. Belflower

Department of Psychology

ABSTRACT: Believing in a benevolent world contributes to positive emotions like joy and contentment, but also more satisfaction with life. Old age is positively associated with benevolent worldviews. Young adults 18-24 have the most cynical worldviews. Since media is readily available to young adults, studies have attempted to use positive content like acts of kindness to examine if it improves benevolent beliefs. Previous research has found that exposure to positive media is associated with increased benevolent behavior among children. The goal of the present study was to see if the intentional moralistic media figure Mister Rogers would improve beliefs in benevolency within the adult population. Eighty-two students from psychology 101 classes participated in the study. Three separate groups watched 10-minute videos then took a benevolence survey at the conclusion of their video. Rocky and Bullwinkle, humorous clips from Marx Brothers movies, and clips of Fred Rogers content was shown in these videos. Those in the Fred Rogers group scored the highest on the benevolence survey with statistical significance compared to the other two media groups. World-based items and authority-based items revealed the largest gaps between the Fred Rogers group and the other two media groups.

Believing the world is a good place contributes to overall wellbeing. Those who believe in a benevolent world experience more positive emotions such as joy, affection, happiness, care, contentment, and love (Poulin & Silver, 2008). Those who believed in a benevolent world also reported higher levels of satisfaction in their life. However, the belief that others are trustworthy has declined in America. Only 34% of Americans agree with the statement “Most people can be trusted” (Miething et al., 2020). In the same study, Miething and colleagues (2020) discovered a lack of trust is positively associated with a 13% increase in a cardiovascular related death. Seemingly paradoxical, the belief in a good world grows as a person ages, even if they have endured more malevolence on average than a younger adult (Poulin & Silver, 2008). These authors believed the elderly understood the finality of their life, so they prioritized positive thinking compared to younger adults in the study. This belief aligns with Carstensen and colleagues (1999) work on the socioemotional selectivity theory which claims older adults pursue emotional related goals versus knowledge-based goals as they age.

Even if a person has not been a victim of a malevolent act, screens give us increased access to seeing the evil side of the world both in non-fiction and fictional contexts (movies, TV, and video games). Much research has been devoted to understanding the negative impact of violent content on a person’s belief system, propensity for violence, and desensitization towards violence. In a longitudinal study, children who were exposed early in life to violent television were more likely to become aggressive as they aged, and some displayed antisocial traits (Huesmann et al., 2003). Anderson and colleagues (2010) found that violent video games increase violent thoughts, aggressive behavior, and reduce prosocial empathetic behavior.

Less research has been conducted on positive influential people in the media and positive content to see if these things increase beliefs about the benevolence of the world and people. When showing positive entertainment to adults, studies often discuss elevation and physiological responses as the mediator to becoming inspired and wanting to live more virtuously such as a study done by Oliver and colleagues (2012). In this study, participants were asked to name their favorite films across multiple genres. The participants were also asked what bodily sensations they felt while watching. This was to gather information about physiological elevation felt during the film. In this same study, the participants picked emotions and motivations from a list to describe how the film made them feel. The virtuous films that elicited more emotional elevation were positively associated with the desire to be more moral when picking motivations from that list.

A study by Neubaum and colleagues (2020) showed video content to participants 6 days per week over the course of 6 weeks. There were 3 groups in the experiment: neutral content, violent content, and acts of kindness content. The researchers hypothesized that exposure to random acts of kindness videos over time would increase prosocial activity, aid in psychological wellbeing, improve benevolent views of humanity, and this cohort would interact with stereotyped groups more often than the participants who watched other forms of content. Those watching the acts of kindness did not show a difference in prosocial activity, psychological well-being, benevolent beliefs, or greater interaction with stereotyped groups compared to the neutral and violent content groups. Their hypotheses were unsupported by the data.

A study by Coates and colleagues (1976) observed preschool aged children, and it was discovered that watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood increased prosocial behavior with their peers and the adults in the classroom. The children used more positive reinforcement whether they were high reinforcers or low reinforcers at baseline prior to viewing the program. Being a high reinforcer meant the child was using encouraging language with their peers often while the low reinforcers were not engaging in this type of encouragement regularly. This behavior continued after the “treatment” phase into the posttest period when no content was shown. Overall, the television program increased social contacts.

Past literature establishes that believing in humanity’s goodness improves quality of living. Nevertheless, finding ways to build this belief in the younger adult population proves difficult unless that person encounters a real-life act of altruism directly. Hoffman and colleagues (2020) recruited participants who received a real-life altruistic encounter and asked them to report how it made them think and feel. Palpable real-life selflessness was shown to have a positive effect on opinions about kindness (Hoffman et al., 2020). The act positively affected their views on humanity’s kindness, it increased their own personal feelings of empathy, and even bolstered their self-esteem, desire to help others, and made them feel valued in the world.

Fred Rogers embodied real-life altruism since he was not playing a character but was Mister Rogers in his daily living. When creating his show, Fred Rogers was intentional about affirmation and onscreen displays of kindness. Every episode he would look directly at the lens of the camera into the child at home and tell them “I like you.” Many of his songs were affirmation and empathy based because he was bullied. So, these themes became a core pillar of the show (Tuttle, 2019). In the present study, the Mister Rogers video acted as real-life altruism and positive media combined. The participants in the Fred Rogers group watched clips from his children’s show which displayed positive unifying moments of kindness between people and puppets living in his television neighborhood. Some clips had intimate affirmation-based messages directed at the viewer. This group also watched parts of his documentary which was created for adults. This film featured his positive impact on both children and adults in real life, not just within the confines of his television program.

The main question of the current research was if clips from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and his documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? would improve beliefs about benevolence in young adults since the show increased children’s prosocial activity (Coates et al., 1976). Fred considered simple messages to be universally helpful “I feel so strongly that deep and simple is far more essential than deep and complex,” he once said to his actual next-door neighbor. (Edwards, 2019). There are many publicly known anecdotal stories of his positive effect on adults like the Esquire journalist Tom Junod and the people who worked for him. There are also anecdotal stories of those who a acquired a positive belief system from “befriending” him after his death by reading his books and watching his content. Until the present study, there was no empirical data to support his positive effect on adults’ worldviews. It was hypothesized that those who watched Fred Rogers content would respond more positively about the world and mankind on a benevolence survey than those who watched other media content.

Method

Participants

120 participants were recruited from Psychology 101 courses at a southeastern university using the online SONA system. 38 participants were excluded for starting the survey and not finishing, skipping answers, or failing to answer basic quiz questions about the material in their group’s assigned video. 82 participants completed the study and demonstrated they paid attention to the content of their group’s assigned video when quizzed. Demographic data such as sex, age, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status was not obtained for this study. Participants earned course credit for participating.

Procedure

On the SONA system there were 3 separate studies listed with a coded name so the participants were unaware of what they were signing up to do and see. Each of these 3 studies represented a separate media group in the experiment: Rocky and Bullwinkle, The Marx Brothers, and Fred Rogers. The study opened on October 13th, 2022 and reached full capacity on October 25th, 2022. Each group contained 40 sign-up slots. There were sign-up restrictions set-up in SONA so that participants were denied access to sign up for more than one group of this study.

The participants completed the experiment using Qualtrics, an online survey and data collection tool. Each group followed the same steps in the same order. The only difference between groups was the media watched and the quiz questions about that particular video. The participants watched the video clip for their specific group, they were asked 4 simple quiz questions about the content they watched. These questions spanned from the beginning of the video to the end and were story or theme based such as the name of the whale in the Rocky and Bullwinkle episode, how Harpo Marx drove away costumers from a rival food stand, and what Daniel Tiger’s fear was when speaking to Lady Aberlin on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. After answering these quiz questions, they took a benevolence survey. The final question for each group was a manipulation check with two possible answers. For Rocky and Bullwinkle that question was: Did you think (A) “The cartoon was something you wanted to watch more of” or (B) “The cartoon felt boring.” For The Marx Brothers group: Did you think (A) “The humor style is harmless” or (B) “The humor style is at a person’s expense.” For the Fred Rogers group: Do you believe that Fred Rogers was (A) “A caring person” or (B) “Had wrong intentions.”

The quiz revealed which participants watched the video in its entirety and paid attention to the content shown. If the participant missed 2 of the 4 quiz questions, their data was excluded. They were told in advance they would be quizzed on the content in the video. By missing more than 1 question, it was determined they may not have paid full attention to the video or only watched a portion. These questions covered the full duration of the video. After excluding participants in each of the 3 groups, there were 26 in the Rocky and Bullwinkle group, 26 in the Marx Brothers group, and 30 in the Fred Rogers group.

Measures

A pool of 28 statements from two scales were used to create the benevolence survey in this study. The first eight questions were from the benevolence section of the World Assumption Scale (Janoff-Bulman, 1989). These 8 statements are world and society focused such as “There is more good than evil in the world” and “If you look closely enough you will see the world is full of goodness.” The WAS also examines the innate traits of humankind, “Human nature is basically good.” This section was chosen for its face validity to measure views on broad world and humanity-based goodness. The next 20 statements were items from the Belief in Human Benevolence Scale (Thornton & Kline, 1982). These statements are people-based items such as “People don’t care what happens to other people” and “People will be kind to you if you are kind to them.” All statements, in the order in which they were presented, are shown in Table 1. The survey was a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree 2 = disagree 3 = somewhat disagree 4 = somewhat agree 5 = agree 6 = strongly agree. There was no neutral option. The survey was scored backwards for questions such as “It is natural for people to be nasty to each other.”

Table 1

All 28 statements used in the benevolence survey

|

Statements |

Scale |

|---|---|

|

1. The good things that happen in this world far outnumber the bad |

WAS |

|

2. There is more good than evil in the world |

WAS |

|

3. If you look closely enough you will see the world is full of goodness |

WAS |

|

4. The world is a good place |

WAS |

|

5. People don’t really care what happens to the next person |

WAS |

|

6. People are naturally unfriendly and unkind |

WAS |

|

7. People are basically kind and helpful |

WAS |

|

8. Human nature is basically good |

WAS |

|

9. People are basically trustworthy |

BHB |

|

10. People who run big companies don’t care about the people who work for them |

BHB |

|

11. People are pleased when they see someone happy |

BHB |

|

12. When someone says something complimentary about you it means they want to get something from you |

BHB |

|

13. Businessmen are honest |

BHB |

|

14. People don’t care what happens to other people |

BHB |

|

15. The way to get on in life is to be cooperate and friendly |

BHB |

|

16. People will take advantage of you if you work with them |

BHB |

|

17. People are basically unselfish |

BHB |

|

18. People are unwilling to make sacrifices for the sake of others |

BHB |

|

19. People will be helpful to you if you are helpful to them |

BHB |

|

20. Given the opportunity people are dishonest |

BHB |

|

21. Bosses do their best for the people who work for them |

BHB |

|

22. People enjoy hearing about other people’s failures |

BHB |

|

23. In order to get anything worthwhile done you have to cooperate with people |

BHB |

|

24. People are unsympathetic to anyone who is unhappy |

BHB |

|

25. People are honest |

BHB |

|

26. The way to succeed is to disregard other people |

BHB |

|

27. People will be kind to you if you are kind to them |

BHB |

|

28. It is natural for people to be nasty to each other |

BHB |

Materials

The 3 groups viewed different forms of content. Each video clip was 10 minutes long. One group watched a segment of the 1960s cartoon Rocky and Bullwinkle. This media type was chosen because cartoons do not show actual human beings. The cartoon was meant to act like a control in that the cartoon was boring, however, the manipulation check revealed over 50% of the group chose option (A) “The cartoon was something you wanted to watch more of.” The cartoon had two sections. The first was Rocky and Bullwinkle finding out about a contest to catch “The wailing whale.” It was a whale the cartoon called “Maybe Dick” instead of “Moby Dick.” The whale was tormenting the navy and an award was posted for whoever could catch the whale. The second section was a humorous version of the classic fairytale Rapunzel. In this adaptation, the prince could not use her hair. This led to him trying unconventional ways to get up the tower. He created a catapult using a tree and a large stone, and then lived among birds so he could learn how to fly.

The humor group watched two scenes of the Marx Brothers in their films Duck Soup and Animal Crackers. The Marx Brothers were slapstick vaudeville performers often using physical humor like kicking and falling but were also known for being tricksters within their films. In the first scene the brothers are harassing a man at a lemonade stand selling his lemonade next to their peanut cart. They purposely try to disorient the man by finding ways to switch their own hats with his hat throughout the scene. Harpo Marx steals the man’s hat and catches it on fire. Later that day in a new hat, the man retaliates by stealing a bag of peanuts from their cart in front of them. Harpo and his brother disorient him again and Harpo lights his hat on fire again on the peanut warming flame of their cart. The man pushes the peanut cart over so Harpo dunks his feet in the man’s vat of lemonade in front of his customers. After seeing this, they leave because they no longer want to drink the lemonade. In the second scene, the brothers are playing a game of bridge with two women. They cheat by showing cards while the women are looking down. They also throw unwanted cards across the room when the other players are not looking. They win by a large margin and when the women decide to leave, one of them realizes Harpo has stolen and is wearing her shoes.

The last group was the Fred Rogers group. This group watched portions of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and his documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? The first clip was from Mister Rogers’ show. He asks a young boy named Jeff why he needs a wheelchair. Jeff explains his medical condition and then he and Mister Rogers sing the song “It’s You I Like” together. There was a portion of Mister Rogers singing his song “I Like You” as he looks at the camera swinging on the porch swing. This swing was part of his porch setup outside his classic television house. There is a clip from the documentary of actor Francois Clemmons (he played the police officer of the neighborhood) saying Fred was the first man to say “I love you” to him. Francois said neither his father nor his stepfather ever said it to him. The next clip is the puppet Daniel Tiger explaining how he is a mistake. He begins to sing about the fear of being different from everyone else. Lady Aberlin sings back to him and tells him that he is fine exactly the way he is. The final clip is Fred asking people to be grateful for the people in their lives and gives them a moment to think about those who loved them into loving or cared about them “beyond measure.”

Results

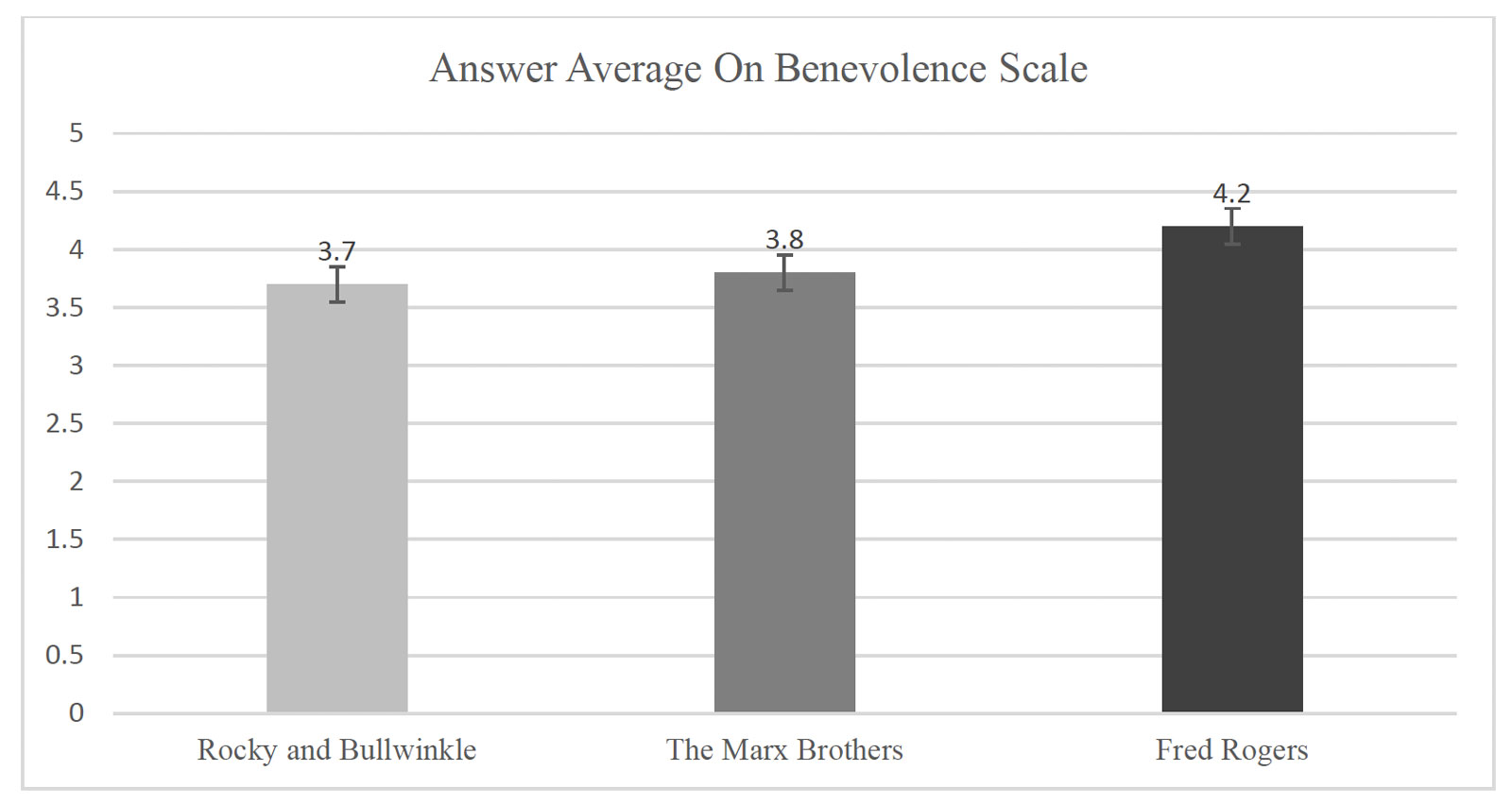

Overall Benevolence Survey Score Comparison

To compare the average group score on the benevolence survey, a one-way ANOVA was performed. This initial ANOVA revealed there was a statistical significance between the 3 media groups F (2,81) = 7.97, p less than .001. Means were plotted, descriptive statistics were obtained, and a Bonferroni correction was then run to observe the pairwise comparisons between the groups overall. The Rocky and Bullwinkle group had the lowest per item score average (M = 3.7). The Marx Brothers group had a slightly higher per item average (M = 3.8). The group with the highest average per item was the Fred Rogers group (M = 4.2). Figure 1 visually presents the per question average for each of the 3 media groups when combining all 28 items on the survey together.

Figure 1

Per Item Average for Each Media Group

Note. This represents the average per question when combining all 28 items on the survey together.

Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni correction revealed the Fred Rogers group showed a very significant difference in survey scores per question when compared to the Rocky and Bullwinkle group (p less than .001). The Fred Rogers group was also significant when compared to the Marx Brothers group (p = .027). There was no statistically significant difference between the Rocky and Bullwinkle group and the Marx Brothers group (p =.680). Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and post-hoc comparisons for each group on the benevolence survey.

Table 2

Descriptive Characteristics and Pairwise Comparisons

|

Group |

n |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Rocky and Bullwinkle |

26 |

3.7 |

.48 |

|

.680 |

less than .001* |

|

2. The Marx Brothers |

26 |

3.8 |

.52 |

.680 |

|

.027* |

|

3. Fred Rogers |

30 |

4.2 |

.53 |

less than .001*</ |

.027* |

|

Note. M and SD represent mean and Standard Deviation per question, respectively.

* p less than .05

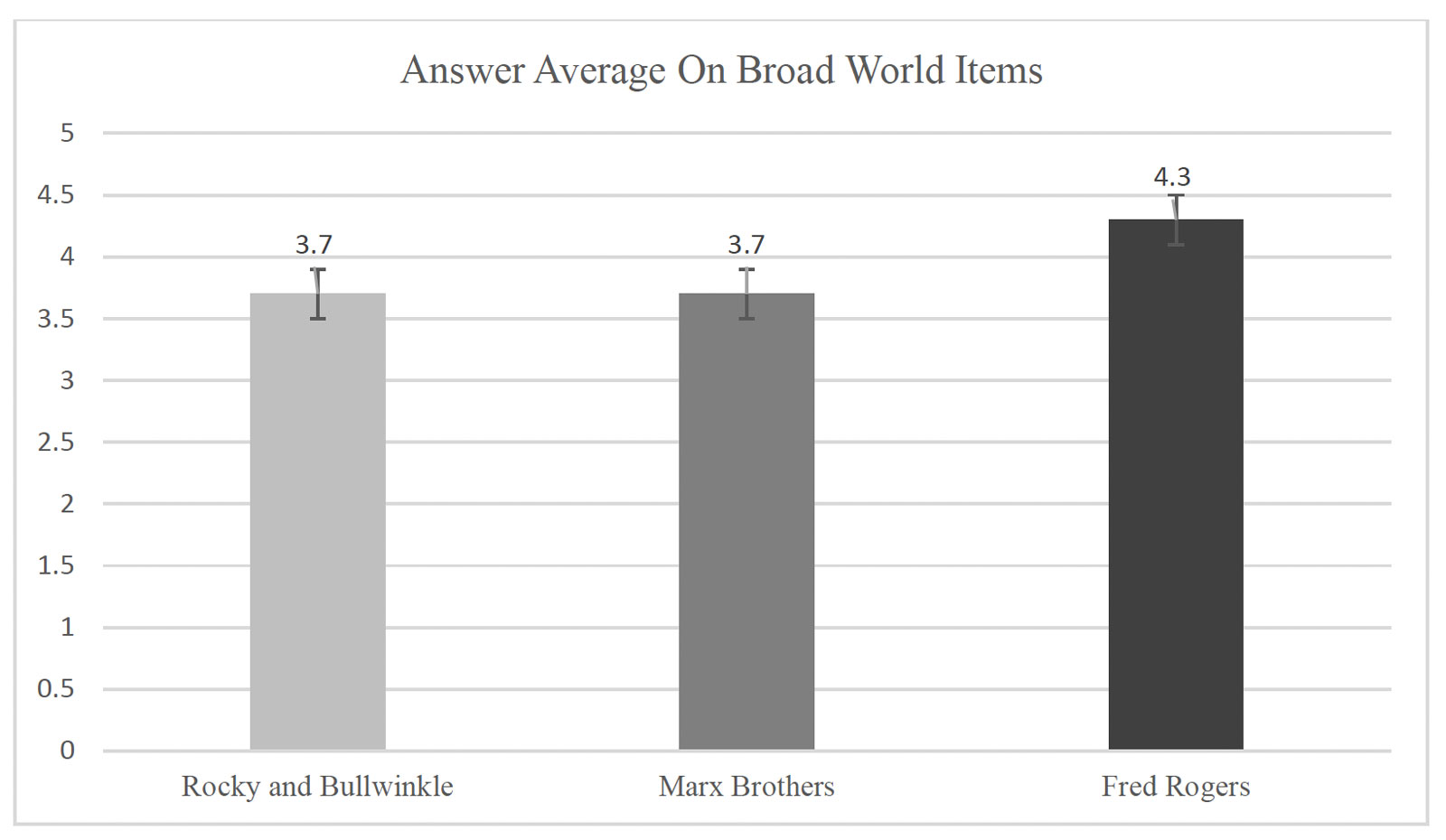

World-Based Items Score Comparison

As indicated in the measures section, the benevolence survey included multiple statement categories within one questionnaire. Post-hoc testing was performed to assess the differences between the groups on certain categories of statements. Items from the benevolence section of the World Assumption Scale (Janoff-Bulman, 1989) contained broad statements about the goodness in the world and human nature overall such as: “The good things that happen in this world far outnumber the bad.” A one-way ANOVA was run on these 5 statements. This ANOVA also revealed a significant difference between the 3 media groups F (2,12) = 6.85, p = .010. The Rocky and Bullwinkle group and the Marx Brothers group had the same mean score per item (M = 3.7). The Fred Rogers group had the highest average on these statements (M = 4.3). Figure 2 presents the average answer on these items. The Fred Rogers group was statistically significant when comparing the groups using a Bonferroni correction (p = .023). The p-value was the at same significance level p =.023 for both the Rocky and Bullwinkle group and the Marx Brothers group since they had the same mean score per item (M = 3.7).

Figure 2

Per Item Average On Broad Benevolent World Assumptions

Note. This represents the average per statement on the 5 items about the world and humanity’s overall goodness.

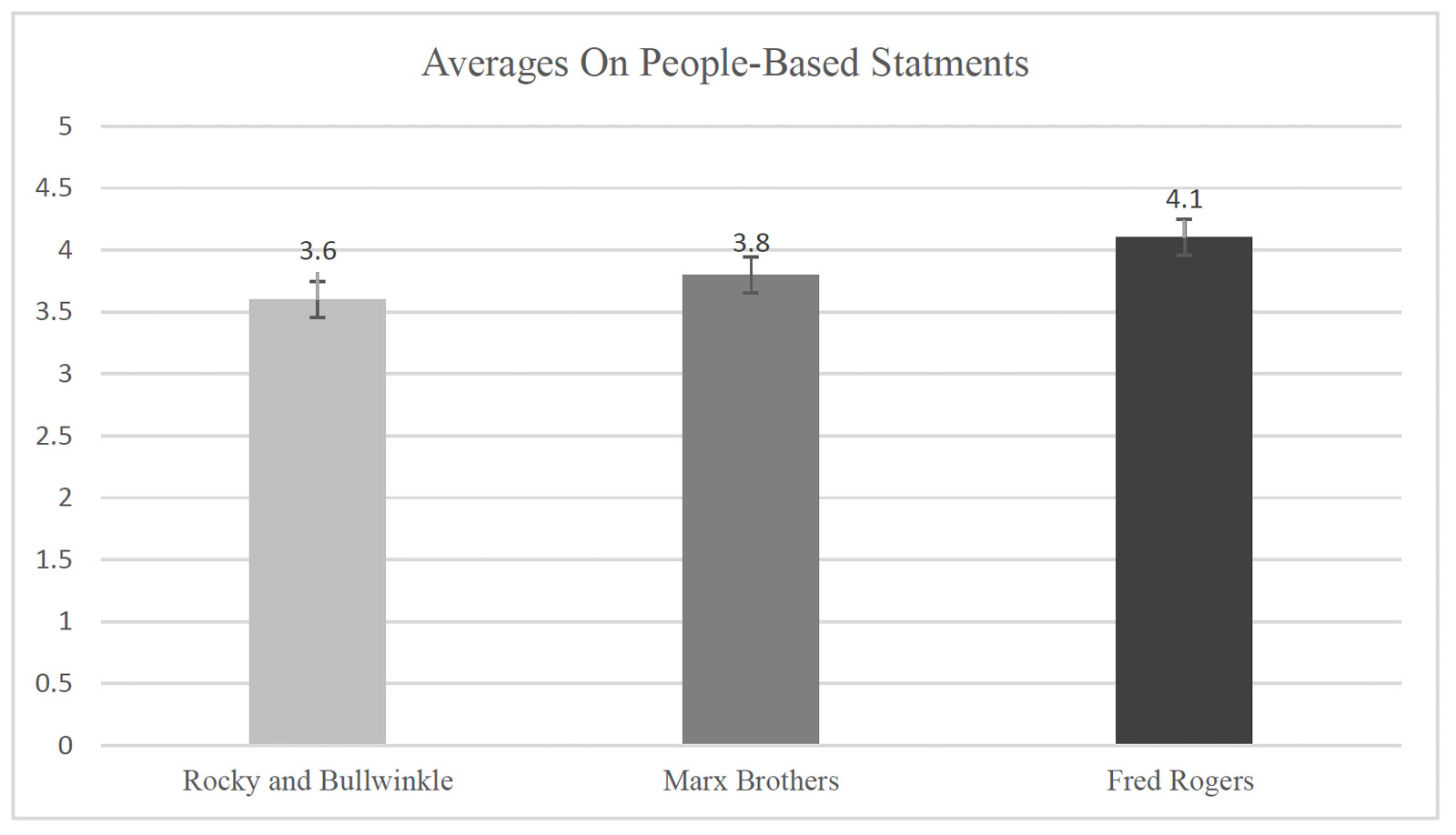

People-Based Items Score Comparison

On the benevolence survey there are 14 items specifically aimed at evaluating opinions about the benevolence of people. A one-way ANOVA was performed on these statements. The initial ANOVA yielded a significant result F (2, 39) = 3.9, p = .027. The Rocky and Bullwinkle group had the lowest answer average on people-based statements (M = 3.6). The Marx Brothers group had a slightly higher average than the Rocky and Bullwinkle group (M = 3.8). The Fred Rogers group had the highest mean on people-based items (M = 4.1). A Bonferroni correction was then used to compare the group averages. This post-hoc test revealed the Fred Rogers group was significant against the Rocky and Bullwinkle group (p = .029). The Rocky and Bullwinkle and the Marx Brothers group did not show any statistical significance (p = 1.00). The Marx Brothers and the Fred Rogers group also did not show statistical significance (p = .159). Figure 3 presents the answer averages for people-based items on the survey.

Figure 3

The Answer Averages for People-Based Benevolent Statements

Note. This represents the average per statement on the 14 items about the benevolence of people.

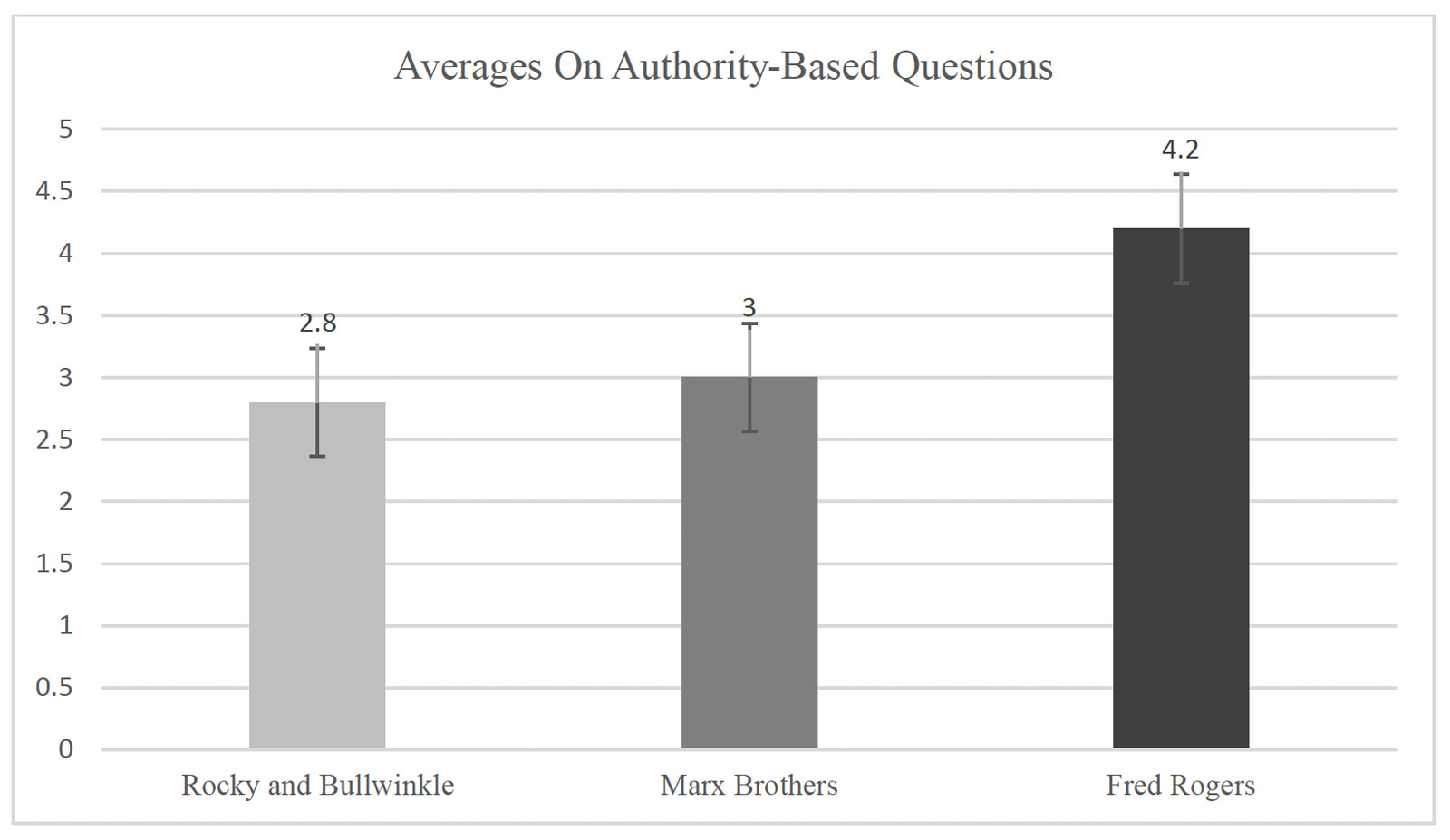

Authority-Based Items Score Comparison

The benevolence survey contained 3 items concerning the benevolence of those in authority such as: “People who run big companies don’t care about the people who work for them.” These types of statements are scored backwards so that more disagreement equates to a higher score. A one-way ANOVA was performed to compare the 3 media groups’ average on authority-based questions. This initial ANOVA showed a significant result F (2,6) = 11.4, p = .009. The Rocky and Bullwinkle group had the lowest average on these items (M = 2.8). The Marx Brothers yielded a slightly higher average (M = 3). The Fred Rogers group had a substantially higher mean on items about the benevolence of authority figures than the other 2 groups (M = 4.2). After running a Bonferroni correction, the Marx Brothers group and the Rocky and Bullwinkle group were not statistically significant from each other (p = 1.00). The Fred Rogers group was significant when compared to the Rocky and Bullwinkle group (p = .013). The Fred Rogers group was also statistically significant compared to the Marx Brothers group (p = .028). Figure 4 displays the average scores of the 3 groups on authority-based statements.

Figure 4

Per Item Average on Authority-Based Statements

Note. This displays the average per statement on the 3 items about the benevolence of authority.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate if watching Fred Rogers would positively affect adult opinions on the benevolence of the world and people. Overall, the Fred Rogers group reported more positive views about the goodness of the world and mankind. This was particularly evident on items related to the goodness of the world and the benevolence of authority figures. The empirical results supported the hypothesis which predicted the Fred Rogers group would respond more positively on a benevolence survey than the groups who watched other content.

This result reflects a similar finding by Coates and colleagues (1976). However, in their study the sample consisted of children in preschool who displayed more prosocial behavior after watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Although the present study did not observe adult behavior, the adults who watched the Fred Rogers video answered the survey with more positive prosocial worldviews than the other media groups. At the moment, it is unknown whether viewing Fred Rogers related content would increase prosocial behaviors in the adult population. Media, whether positive or negative, can affect behavior, beliefs, and motivations in both children and adults (Anderson et al., 2010; Coates et al., 1976; Huesmann et al., 2003; Oliver et al., 2012).

Neubaum and colleagues (2020) hypothesized the group in their study that watched random acts of kindness would report more positive views on humanity, but their hypothesis was not supported. The current study’s hypothesis was supported, and this experiment did not include a violent content group. Each group in the current study viewed tame media, but the Fred Rogers video contained simple powerful messages along with a display of Fred’s genuine kindness. A possible explanation of why the present study yielded a significant result is that Fred Rogers did not engage in random acts of kindness, but instead lived a life of kindness and empathy every day both on and off screen. Participants watched one person consistently caring in the Fred Rogers group, and not various strangers engaging in altruistic acts. They also heard from adults in the documentary clips who personally worked with him and testified on behalf of his life built on intentional kindness.

An unexpected finding was that the Fred Rogers group displayed a significantly greater belief in the benevolence of authority figures such as businessmen, bosses, and those who run large companies. Fred Rogers was an authority figure because he created the television program. The participants in the Fred Rogers group watched a clip of Francois Clemmons (a main cast member on the show) discussing his powerful connection with Fred in the documentary clip. Francois says in the clip that Fred was the first man to tell him that he loved him. He claims his father, nor his stepfather, ever said “I love you” to him. Francois begins to cry in the clip and says, “I needed to hear it all my life. From then on, he became my surrogate father.” Fred Rogers was Francois’ boss but became a surrogate father to him. This is a possible explanation for why authority figures were seen as more benevolent in the Fred Rogers group. The participants in that group watched an authority figure’s positive impact on an employee.

To the knowledge of the researcher, this was the first time Mister Rogers content was shown to adults in a psychological study. This was a major strength of the present study. Oliver and colleagues’ (2012) study mentioned that components of filmmaking like powerful cinematic music compositions or cinematography can lead to enhanced elevation and inspiration. The Fred Rogers video focused on kindness, empathy, affirmation, and gratefulness. The main purpose of the video was not to induce physiological elevation, but to show positive prosocial behavior. At the end of the survey there was a manipulation check question which asked if the participants believed Fred Rogers had bad intentions or if he was a caring person. All participants in the Fred Rogers group selected the answer that stated he was a caring person. The focus on simple human kindness in entertainment rather than the production itself is also a strength of the current study. Also, unlike Oliver and colleagues’ (2012) study where participants listed their favorite films, Fred Rogers was a real person and not a fictional character in a movie. He represents what our best selves might look like through intention and dedication to others. This study featured one person’s positive impact on many people instead of strangers engaging in acts of kindness which was the content shown in Neubaum and colleagues’ (2020) experiment.

Despite these findings, there are limitations in the current study. The cohort of participants was quite small. 26 participants were in the Marx Brothers and Rocky and Bullwinkle groups and 30 were in the Fred Rogers group. When there is a small sample size in a group, a few participants can affect the overall outcome of that group’s performance on a survey either positively or negatively. In addition, demographic data was not obtained. This data could have given insight into who Fred Rogers influences the most, or it might have shown that his content is universally effective. The environment in which the participants viewed the material is also a limitation. The videos were watched at the participant’s convenience over the internet and not in a controlled space. Though they were able to answer the quiz questions correctly about the video, it is unknown whether they were in a quiet private place or in a public space. Viewing a video in a public setting may distract the viewer or distance them from Fred Rogers’s message. Phone viewing might also be a factor. If the participant watched their video on a cellphone, this may create a different viewing experience because a phone screen is smaller than a computer screen. Since the videos were only 10 minutes long, this is a possible limitation as well. The runtime of a full episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is roughly 30 minutes. The documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? has a runtime of 1 hour and 34 minutes. A longer video highlighting Fred Rogers and his show might have increased beliefs in benevolence, but there could also be a boredom or fatigue factor with longer videos since they were viewing those videos on their own computers or phones.

For future research it is imperative to recruit a larger sample size and do a replication study that includes the gathering of demographic information. A future study could also investigate each media type’s effect on moral decision making. The participant could be given a set of fictious moral decisions to make after viewing their assigned video. A longer-term study would be sensible as well. Neubaum and colleagues (2020) showed their video content to participants over the course of 6 weeks. Another potential type of replication study would be to show full length movies in a research lab environment. The cartoon group would watch a non-emotional animated film, the Marx Brothers group would watch a full-length Marx Brothers film, and the Fred Rogers group would watch the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? With this design there could be an immediate posttest and then a retest at a later date to check for long-term effects in the Fred Rogers group. There are also many other studies that could use the tenets of Fred Rogers’s belief system or implement his daily routine to see if it aids in psychological flourishing and benevolent behavior.

Overall, this study revealed there are gaps in research concerning how to improve the belief in a benevolent world. It would be fruitful for the author and future scholars to expand upon this work and find ways to improve benevolent worldviews in the adult population. This is especially important now that we have easy access to the negative aspects of our world and mankind through technology.

"The media shows the tiniest percentage of what people do. There are millions and millions of people doing wonderful things all over the world, and they're generally not the ones being touted in the news." — Fred Rogers

References

- Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L., Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., Rothstein, H. R., & Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151–173.

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181.

- Coates, B., Pusser, H. E., & Goodman, I. (1976). The influence of "Sesame street" and "Mister Rogers' neighborhood" on children's social behavior in the preschool. Child Development, 47(1), 138.

- Edwards, G. (2019). Kindness and wonder: Why mister rogers matters now more than ever. HarperCollins.

- Hoffman, E., Gonzalez-Mujica, J., Acosta-Orozco, C., & Compton, W. C. (2017). The psychological benefits of receiving real-life altruism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(2), 187–204.

- Huesmann, L. R., Moise-Titus, J., Podolski, C.-L., & Eron, L. D. (2003). Longitudinal relations between children's exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977-1992. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 201–221.

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1989). World assumptions scale. PsycTESTS Dataset.

- Miething, A., Mewes, J., & Giordano, G. N. (2020). Trust, happiness and mortality: Findings from a prospective US population-based survey. Social Science & Medicine, 252, 112809.

- Neubaum, G., Krämer, N. C., & Alt, K. (2020). Psychological effects of repeated exposure to elevating entertainment: An experiment over the period of 6 weeks. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(2), 194–207.

- Oliver, M. B., Hartmann, T., & Woolley, J. K. (2012). Elevation in response to entertainment portrayals of moral virtue. Human Communication Research, 38(3), 360–378.

- Poulin, M., & Cohen Silver, R. (2008). World benevolence beliefs and well-being across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 23(1), 13–23.

- Thornton, D., & Kline, P. (1982). Reliability and validity of the belief in human benevolence scale. British Journal of Social Psychology, 21(1), 57–62.

- Tuttle, S. (2019). Exactly as you are: The life and faith of mister Rogers. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.