| 2008 Case #7 |  |

|

| (Links to Other 2008 Cases are at bottom of this page) | ||

| Diagnosis: Typhoid fever complicated by intestinal perforation. |

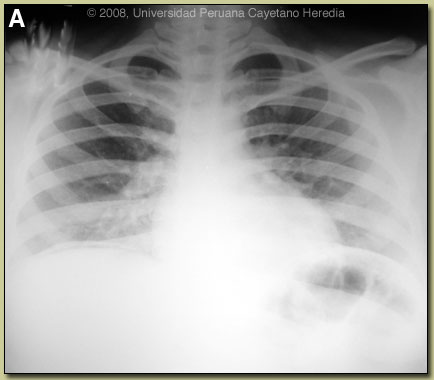

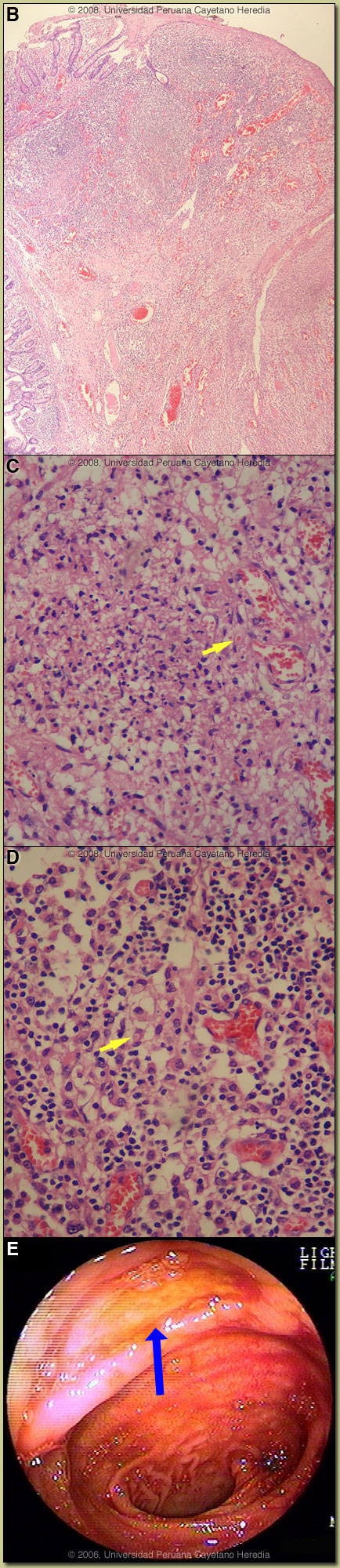

Discussion: The free air noted under the right hemi-diaphragm led to urgent laparotomy. A single perforation (0.5 cm) located 50 cm from the ileo-cecal valve was observed, multiple mesenteric enlarged lymph nodes were also seen, and approximately 200cc of clear fluid was present in the peritoneal cavity. A resection was performed with terminal anastomoses. A Widal test was positive with O 1/320, H 1/320. Image B shows the intestinal perforation surrounded by chronic inflammatory reaction. Image C shows a granulomatous reaction with epithelioid cells. The predominant infiltrate consists of aggregates of histiocytic cells, and is accompanied by some lymphocytes and plasma cells. “Typhoid cells” can also be seen with ingested red blood cells inside [arrow]. In Image D, the typical histopathological finding of so-called “typhoid cells”, tissue infiltration by aggregates of histiocytes containing bacteria and degenerating lymphocytes is shown [arrow]. Discussion: The free air noted under the right hemi-diaphragm led to urgent laparotomy. A single perforation (0.5 cm) located 50 cm from the ileo-cecal valve was observed, multiple mesenteric enlarged lymph nodes were also seen, and approximately 200cc of clear fluid was present in the peritoneal cavity. A resection was performed with terminal anastomoses. A Widal test was positive with O 1/320, H 1/320. Image B shows the intestinal perforation surrounded by chronic inflammatory reaction. Image C shows a granulomatous reaction with epithelioid cells. The predominant infiltrate consists of aggregates of histiocytic cells, and is accompanied by some lymphocytes and plasma cells. “Typhoid cells” can also be seen with ingested red blood cells inside [arrow]. In Image D, the typical histopathological finding of so-called “typhoid cells”, tissue infiltration by aggregates of histiocytes containing bacteria and degenerating lymphocytes is shown [arrow].

Typhoid fever is a systemic febrile illness caused by Salmonella enterica sub-species enterica serotype Typhi. Prolonged fever, sustained bacteremia, and intracellular multiplication of the bacteria within mononuclear phagocytic cells of the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and Peyer’s patches are hallmarks of the infection. Paratyphoid fever is a pathologically similar but milder disease caused by a number of other serotypes of Salmonella. Transmission is usually via contaminated food and water. S. typhi can survive for weeks in water, ice, sewage and on inanimate objects. Stool from chronic carriers can contain from 106 to 109 organisms. Ingested bacteria invade small intestinal epithelial cells and are initially internalized in intestinal lymphoid cells and draining mesenteric lymph nodes. At the end of an incubation period, which is generally 7-14 days but can vary from 3-60 days, clinical disease heralds the onset of the bacteremic phase of the infection. Bacteria may invade any organ but most commonly invade mononuclear cells within liver, spleen, bone marrow, gallbladder and Peyer’s patches. Involved Peyer’s patches are generally in the terminal ileum within 60 cm of the ileo-cecal junction and in the cecum itself. Without treatment, after about 7-10 days of illness, necrosis and sloughing of the overlying mucosa may result with ulcer formation [see Image E from another patient] and more rarely intestinal perforation. Ulcers are usually 1 cm or less in size and most often solitary. Most patients are children and young adults under 25. Clinical manifestations are protean and non-specific but almost always include fever and headache. The headache often results in insomnia. Fever is initially low-grade but by the second week is high (39-40°C) and sustained. There may be intermittent confusion and many patients have an apathetic affect. Complications occur in 10-15% and are more frequent in patients who have been ill for 2 weeks or more. While a large number of complications have been described, clinically obvious gastrointestinal bleeding (10% of all patients), intestinal perforation (1-3% of hospitalized patients), and encephalopathy are the most common. GI bleeding is serious in 2% of all cases. Other, but less frequent infections associated with intestinal ulceration of adenopathy would be intestinal tuberculosis or Yersinia infection. Entameba histolytica and Balantidium coli infection cause ulcers and perforation but would only be found in the colon. Peripheral blood cultures are positive in 40-80% of patients only reaching higher yields if 15 ml of blood are cultured because of the low numbers of organisms in peripheral blood with 80% of those being intracellular. Culture of bone marrow increases the yield to >95% and may remain positive even in the face of several days of antibiotic therapy. Blood cultures yield decreases after the first week of illness. Stool cultures are positive in 30% of cases of acute typhoid fever. The Widal test remains controversial because of highly variable sensitivity, specificity and predictive values in different settings. However, the highly positive Widal test in this patient with this characteristic clinical syndrome strongly supports the diagnosis. Drug resistance in Latin America has not occurred to the same extent as in Asia and other areas of the world. Most of the typhoid in Peru remains sensitive to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfa. Nevertheless, oral quinolones remain the treatment of choice for uncomplicated typhoid due to insignificant rates of relapse and chronic carriage as well as faster times to fever resolution of quinolones compared to the older drugs. Quinolone resistant S. typhi, which has become highly prevalent in Asia, has not emerged in Latin America, so that empiric quinolone therapy can be initiated without reservation in those who acquire infection in Latin America. In febrile patients, clinicians often characterize a non-response of fever after 48 hours as an antibiotic failure and switch drugs. In typhoid fever, response to quinolones most often does not occur until Day 4 or 5 and with chloramphenicol it is usually longer. Many sources continue to list Peru as a highly endemic country for typhoid fever based on data and experience from the 1980s. The cholera epidemic that began in 1991 in Peru and other Latin American countries resulted in the implementation in Peru of many public health and infrastructure changes that had a dramatic bystander effect on typhoid fever incidence rates [Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994 Mar;8(1):183-205] that remain to this day. Prior to 1991, 50-100 cases of typhoid fever presented each year to our hospital. At present, we only see about 20 cases per year though numbers have begun to increase again in the past 2 years. The patient was treated with IV metronidazole and ceftriaxone to cover both Salmonella and other intestinal flora. The clinical evolution was satisfactory; she was discharged after 7 days of parenteral therapy to complete 14 days with oral metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. |