| 2010 Case #1 |  |

|

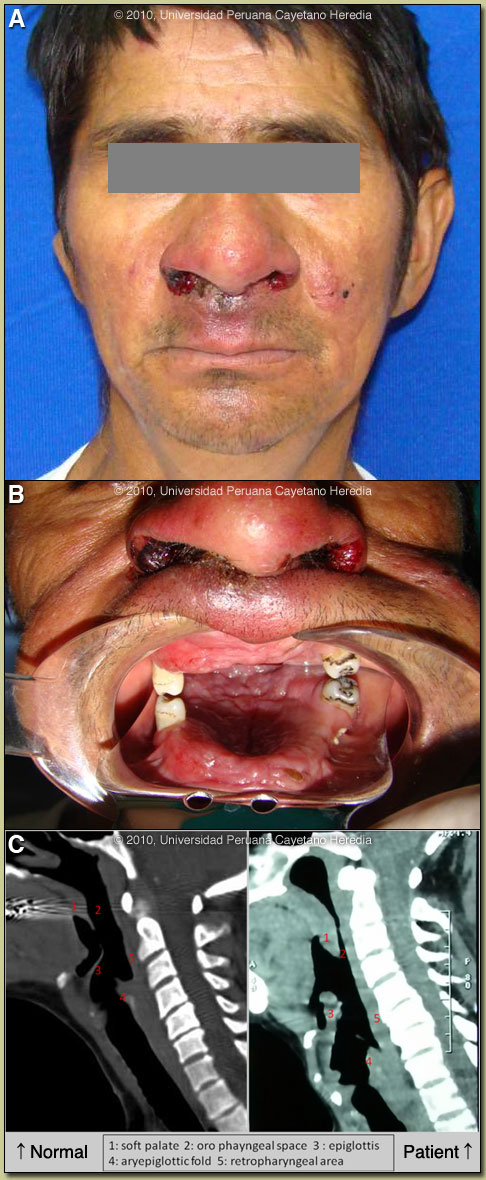

| Diagnosis: Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania braziliensis. |

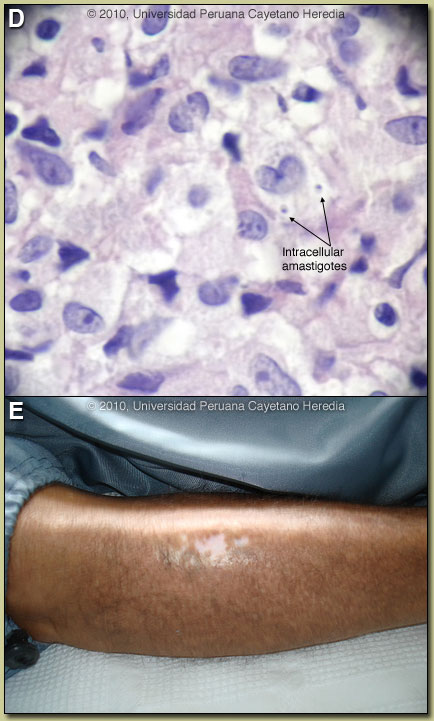

Discussion: Giemsa stain of a scraping from the lesion on the palate disclosed amastigotes.of Leishmania. Culture from the sample was positive in biphasic Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle (NNN) culture medium. Histopathology of a facial lesion: dermal hyperplasia with dense plasma cell infiltrate with a tendency to form granulomas; scant presence of intracellular amastigotes [Image D]. A leishmanin skin test was positive. Official reading of the CT scan indicated extensive involvement of the nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal and retropharyngeal areas, including involvement of the epiglottis and of the aryepiglottic folds. Significant narrowing of the air column was present. Discussion: Giemsa stain of a scraping from the lesion on the palate disclosed amastigotes.of Leishmania. Culture from the sample was positive in biphasic Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle (NNN) culture medium. Histopathology of a facial lesion: dermal hyperplasia with dense plasma cell infiltrate with a tendency to form granulomas; scant presence of intracellular amastigotes [Image D]. A leishmanin skin test was positive. Official reading of the CT scan indicated extensive involvement of the nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal and retropharyngeal areas, including involvement of the epiglottis and of the aryepiglottic folds. Significant narrowing of the air column was present.

L. braziliensis is the only leishmania species present in the area of the jungle where he lived at the time of his initial infection 20 years earlier. However, in South America it is important to definitively distinguish Leishmania species that cause only cutaneous disease (e.g., L. peruviana in Perú) from the mucocutaneous species. Both typically cause one or a few initial skin lesions that are ulcerative but painless in nature and that usually spontaneously heal over time. However, with L. braziliensis (the mucocutaneous species), severe destructive recurrence may occur in the mucosal surfaces of the naso- and oropharynx from months to years (as in this case) after treatment or healing of the skin ulcers. L. braziliensis only occurs in the Americas and is the only Leishmania species that causes mucocutaneous disease. In this part of the world the vector is the Lutzomyia sandfly. The major differential diagnosis in Perú of these oro-pharyngeal lesions would be paracoccidioidomycosis, carcinoma, or lymphoma. In Perú leishmaniasis would be by far the most common. The painless nature of the mucosal lesions despite widespread destruction of tissue, involvement of the mucosa, as well as spread to the larynx are consistent only with leishmaniasis. Without the facial cutaneous lesions, pharyngeal and laryngeal lesions could also be consistent with rhinoscleroma, a granulomatous bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. A search for the scar of the original cutaneous lesion, often subtle, usually on a limb, is a key part of the physical examination [Image E from this patient]. Its absence should lend doubt to the impression of leishmaniasis. In general, oral lesions of paracoccidioidomycosis are painful, are frequently friable and bleed on contact, and gingival and buccal mucosa are frequently involved. The lungs are the primary site of infection in paracoccidioidomycosis and the x-ray is generally abnormal. KOH preps of direct scrapings will be positive in up to 90% of cases of paracoccidioidomycosis with oral lesions. Distinguishing L. braziliensis from L. peruviana has usually involved laborious culture techniques followed by electrophoretic isoenzyme analysis. Investigators at our Institute have now published PCR assays using both tissue as well as less invasive specimens [Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Mar 15;42(6):801-9; Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 1;50(1):e1-6] for distinguishing the 2 species from the initial skin lesions. Early identification of the species that causes the initial cutaneous infection would greatly help to prevent mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, because it would allow more aggressive treatment and follow-up. In Perú L. peruviana (cutaneous disease only) occurs only in the high Andes; L braziliensis occurs only in the jungle and in the Amazon. Recommended standard therapy for mucocutaneous disease is generally 28 days of a pentavalent antimonial (sodium stibogluconate 20mg/kg/d). In our Institute, we usually begin with amphotericin B in cases of mucosal involvement at a dose of (0.7 mg/kg/d, IV) to a total cumulative dose of 25 mg/kg. Patients are given pre- and post-treatment hydration and supplemental potassium with daily doses given in an outpatient infusion therapy setting. Liposomal amphotericin may be used in resource rich settings, but based on limited trials it is not better in terms of efficacy even if less toxic and more convenient. Monitoring for failure of initial therapy is done clinically. Lesions that don’t respond at all by the end of the therapy course or don’t cure by 3 months should be considered failures and treated with another drug. Our patient responded well to his initial therapy and his dyspnea and dysphagia have resolved markedly. He also received single dose oral ivermectin for S. stercolaris, and cotrimoxazole for Cyclospora cayetanensis.

|