-

A scientific approach to politics

a scientific approach to politics

Photos Courtesy of Gannon Ray, Left, and Randy wadkins, right

Brian Spurlock

Science Reporter

bspurgbs@uab.eduSince Paula Abdul left American Idol, there have only been two institutions that Americans trust: The United States Military and science.

But, in the wake of Donald J. Trump’s 2016 election, scientists could already feel the tide turning against them. One of Trump’s first acts as President was to endorse sweeping reductions to research funding according to Washington Post.

“There was now a credible threat to scientific progress and scientific thought,” said Cortez Bowlin, graduate in biomedical sciences student and one of the organizers for the Birmingham March for Science.

Other scientists shared in Bowlin’s concern.

“That was the last straw,” said Randy Wadkins, biochemistry professor at the University of Mississippi and Democratic candidate for Congress for the first district of Mississippi. “It wasn’t the only thing, but that’s when I decided ‘maybe this is my time.’ As a scientist, you have a different sort of vision and toolset, and it is irresponsible not to get involved when you look around and see what is going on.”

Many candidates for local, state and national office in 2018 have touted their STEM credentials.

“Several of my friends decided to run and asked me to run as well,” said Gannon Ray, a medical student at South Alabama and former research intern at UAB who ran to join the Alabama GOP Executive Committee. “[We wanted] to root out some of the so-called establishment in Alabama politics.”

Wadkins and Ray said that they may disagree on policy, but they agree that policy decisions could benefit from being tackled with the scientific method, the way in which scientists form and test a hypothesis.

Wadkins said U.S. policy should advance like science, by building on what has worked in other places and seeing if we can go one step further.

Even if STEM training would help politicians, it seems to hurt candidates who are running. In 2018, scientists performed an average of a 3 percent lower than other candidates in the polls, according to an analysis by FiveThirtyEight and Ballotpedia.

Ray lost his June 2018 race to Jerry Lathan, husband of Terry Lathan who chairs the Alabama Republican Party. Wadkins is the underdog in his race against GOP incumbent Trent Kelly.

Ray and Wadkins said they both worry that scientists may come across as standoffish to the average voter. Bowlin said scientists are at a disadvantage because they defend the data without considering what is politically convenient.

“There is a point where doing what is right and doing what is political is not the same thing,” Bowlin said. “As scientists we know that if the data says this and the field says the opposite, you have to defend the data.”

The fix for this, according to Wadkins, one needs to have deep ties to the community where one runs.

“If you don’t live there, if people don’t know you, they’re just going to assume the worst about you,” Wadkins said.

Still, with scientists running and losing, Bowling said he fears that science itself will become political, and not objective.

“[AL Rep.] Mo Brooks argued rocks falling into the ocean could be causing sea level rise,” Bowlin said. “[Phil Duffy], the scientist testifying, said that effect is miniscule compared to what we are seeing. [He] was not trying to say‘vote blue,’ but he is now considered a political operative because he disagreed.”

“Most of the time when you think of a political act, its endpoint is some form of political change,” Bowlin said. “Unfortunately, science has become something like that. I do not think anyone wants it that way.”

-

Using genes to guide treatment

using genes to guide treatment

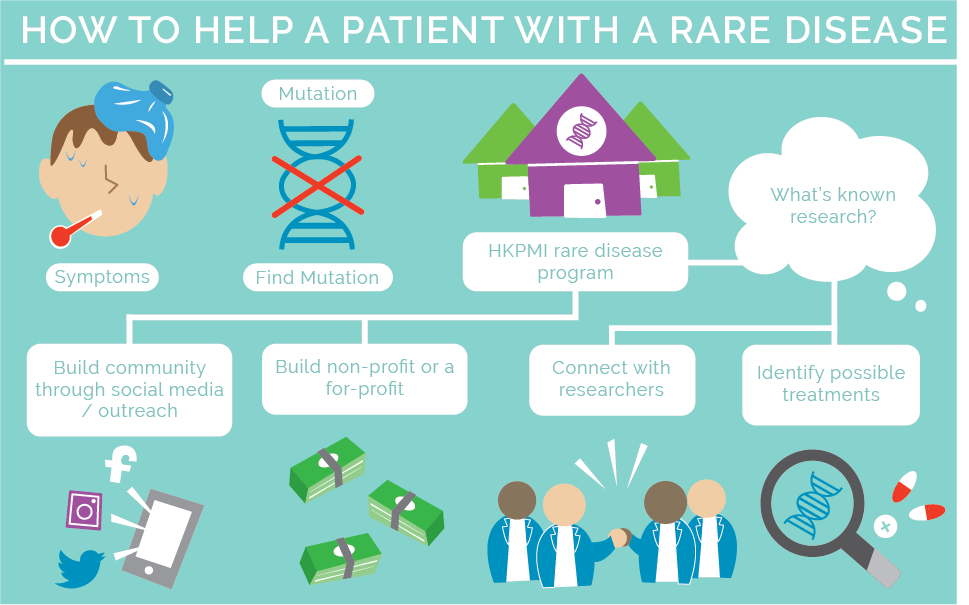

Art by Lakyn Shepard/Art Editor

Brian Spurlock

Science Reporter

bspurgbs@uab.eduThe typical difference between two humans is 0.6 percent of all of our DNA. Along with chance and our environment it is that 0.6 percent that decides everything which makes us unique.

That 0.6 percent can mean redheads are less responsive to anesthesia. Subtle DNA changes in a tumor can decide whether if a patient responds to chemotherapy. Some people’s 0.6 percent has given them a disease no one has ever seen before.

Enter precision medicine.

The Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute (PMI) was founded in 2014 with a $7 million grant from the Hugh Kaul Foundation. Its goal is to identify treatments based on every individual’s need, reading it from their DNA.

Matthew Might, director of PMI, journey in precision medicine began when his son Bertrand became the first person in the world diagnosed with a rare genetic disease which caused him to start losing his vision, have seizuresand experience developmental delay.

Might has made his life’s work helping others with rare diseases find that same relief as his son.

“It…took a person like Matt to have done this journey as a driven parent, but to also have come from science and academia to sort of bridge the gap,” said Andy Crouse, director of Research and Operations at PMI.“What’s been great about this team with Matt is, it’s taking that next step. Not just saying what’s wrong, which is important, but how we can help after that.”

Word of mouth is crucial. Patients from all over the world hear about the Rare Diseases program and reach out to Might’s team.

“I had a case from Norway this summer,” said Jordan Barnham, Precision Medicine Specialist on Might’s team. “People just find us.”

From there they enter a “pipeline” to identify how the team can best help them.

Part of the team’s mission is to connect patients with mutations in the same gene or pathway with each other and with scientists who might be able to help.

Another part is poring over the research for everything that written about that gene or variant, said Lindsay Jenkins, Precision Medicine Specialist and senior in genetic and genomics sciences and neuroscience.

Jenkins and Barnham are part of a team of three undergraduate students who, along with an artificial intelligence developed by the institute’s computer scientists,search databases and Google for hints of a drug, treatment or pathway that might offer relief to patients.

“Our goal is to hopefully take a patient from when they first come to us to some kind of therapeutic or treatment within a year,” Barnham said.

“I think the trust that is put into us as undergraduates in this position is not something you’re going to find anywhere else,” said Jenkins. “We’re the ones who find a treatment for our patients and propose it in a meeting.”

One of the program’s aspirations, according to Barnham, is to be a major leading center in drug repurposing and therapeutics for undiagnosed diseases.

Specialists do not have a maximum case load, though Crouse said he admits that may have to change as they grow.

“This group loves doing this,” Crouse said. “It’s not like ‘I only dedicate my three hours.’ It’s something they think about all the time. If we gave them more, they would just do more.”

All three used the word “rewarding” when talking about their work. They get to see the difference they make in real people’s lives, and they come across as immensely grateful.

The institute also boasts branches for pharmacogenomics, which are interactions between the 0.6 percent, medicines used to treat a variety of diseases, and precision cancer research.

“We have several more patients starting or nearing treatment, and we've asked them to let us follow their stories,” Might said. “I'm hoping we'll have more shareable success stories in the next few months.”

In the meantime, the institute is actively encouraging people to reach out if they want to get involved or if they know patients who may benefit from one of these programs, Barnham said.